Case No. 4,877.

9FED.CAS.—19

FLOOD v. HICKS.

[2 Biss. 169; 4 Fish. Pat. Cas. 156; 1 Chi. Leg. News, 377; Merw. Pat. Inv. 193.]1

Circuit Court, N. D. Illinois.

July Term, 1869.

PRIORITY OF INVENTION—SIMILARITY.

1. A patent for an improvement in a wagon reach, consisting of an upward curve, whereby, in turning, the forward wheels are allowed to pass under the reach, combined with an extension of the ordinary sway-bar, so arranged upon the hounds that it will still form a support for the reach, can not be sustained when it is proved that a carriage fitted with a reach which had a bend allowing the wheels to pass partly under, and with a circular sway-bar or wheel by which the reach would be sutained in all positions, had been in use for several years.

2. Increasing the curve in the reach, or diminishing the diameter of the wheel, would allow it to pass completely underneath, as in the plaintiff's patent; and this is a change which would naturally suggest itself to any mechanic, and cannot be the subject of a valid patent when the substantial invention had been previously in use.

[Cited in Preston v. Manard, 116 U. S. 664, 6 Sup. Ct. 697.]

3. The circular sway-bar would have performed the same office as the plaintiff's improved extended sway-bar, had the wheel passed beneath the reach, and the plaintiff's patent for the curved reach having failed, his claim for the improved sway-bar must fail with it.

4. The name by which any structure or part is designated is immaterial.

This action was a suit at law for infringement. The parties waived a jury, and the cause was by consent tried by the court.

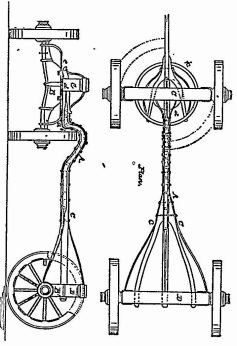

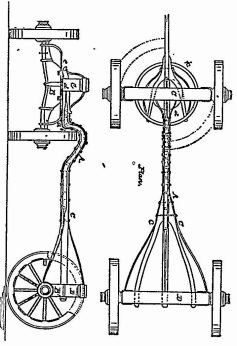

[Drawings of patent No: 69,789. granted October 15, 1867, to E. F. Flood. Published from the records of the United States patent office.]

L. L. Bond, for plaintiff.

S. A. Goodwin, for defendant.

DRUMMOND, District Judge. The plaintiff claims, by virtue of a patent, dated the 15th of October, 1867 [No. 69,789], an improvement in a wagon reach, and the allegation is that the defendant, who also has a patent, 290dated the 27th of October, 1868, violates the patent of the plaintiff.

The specifications attached to the plaintiff's patent describe the particular manner in which the reach is made, and declare that the object of the invention is so to construct the reach that the vehicle with which it is used can be turned in the least possible space, and so that the wheel can never strike against the reach; and this object, it is said, is accomplished by the peculiarity of the form of the reach, the peculiarity being by giving it a turn or curve upward at the point where the wheel would strike an ordinary reach, which is always straight.

The claim of the plaintiff consists of two parts. He claims, First, a curved or bent reach, when so constructed that the line of draft is the same as in a straight reach, and so that the reach rests on and is supported by the sway bar, as in the ordinary reach, substantially as described in the specification; and secondly, he claims a curved reach—referring to the drawing A in combination with the iron E of the sway bar, when such iron is extended, and so constructed as to furnish a support for the reach in all positions, substantially as and for the purpose mentioned.

This last claim consists of the extension of the ordinary sway bar upon which the reach rests, which bar is usually placed upon hounds, as they are termed, round and forward, so that the reach shall rest upon the sway bar, when the forward wheels of the wagon pass under the reach and are placed at right angles with the hind wheels.

The question is, whether this patent can be sustained, in view of the evidence which has been produced before the court. No question was made, and, of course, none can be made, that if the plaintiff's patent is sustainable, the defendant's wagon or reach infringes, and therefore the only question is whether the plaintiff's patent can stand.

I am of opinion that it is not sustainable in point of law, under the facts which have been adduced.

The position taken by the counsel of the plaintiff as to the first claim, was that it was not a broad claim for a bent reach, but that it was a claim for a bent reach under certain conditions, one of which was that the line of draft must be the same as in a straight reach, and another that the curve must be so returned to the straight line that the reach will rest on the sway bar and be supported by it, and thirdly, that it must be so curved that the wheels must not strike against it. Taking that view of it, can the claim be sustained?

It was in evidence that a wagon or carriage had been used for many years, manufactured as early as 1854 or 1855, in which the reach had a bend or curve upward, so as to admit of the forward wheels passing under the reach to a certain extent, when the carriage was in the act of turning, and with a sway bar, or what is sometimes called the fifth wheel of the wagon, forming an entire circuit, resting upon the forward axle and upon the hounds.

It is true that in this carriage the forward wheels could not pass entirely under the reach, but it is clear to my mind that when the idea is once presented of a curve or bend in the reach, so as to admit of the forward wheel passing to a certain extent beneath the reach, that you have got the substantial invention of the plaintiff, so far as concerns the reach, because the idea once being suggested that by a curve in the reach the wagon or carriage is permitted to make a sharper turn by the forward wheels going partially beneath the reach; all you have to do is to make the bend greater or the forward wheels smaller, and you accomplish to all intents and purposes the object stated by the plaintiff. That is to say, by elevating the curve more or diminishing the circumference of the forward wheels, either, or by both combined, you cause the forward wheels to pass completely under the reach, and with this carriage before us as it was, bodily in court, and which had been in existence some fifteen or sixteen years, it was not possible to say that a man could have a patent simply by making the curve greater in the reach or diminishing the circumference of the forward wheels of the carriage. There is the idea. There is whatever of invention there is, and it is a mere mechanical expedient to change the structure either of the reach or of the forward wheels.

Again, so far as the sway bar is concerned. In that carriage thus having existed for so long a time, there was this circular sway bar, sometimes called the fifth wheel, and it was clear that if the wheel was lessened so as to pass beneath the reach, or the curve increased, that the reach would rest upon the sway bar as the carriage was turned and as the wheels passed beneath the reach. It is because the idea is apparent in the carriage that was manufactured some fifteen years ago, of the effect of the curve in the reach, that the first claim of the plaintiff's patent cannot be sustained. In that the reach passed from the axle of the hind wheels in a straight line toward the axle of the forward wheels until it came to a curve, and then there was a sweep upward and it came down to a straight line and was so continued on to the axle of the forward wheels.

The idea in the first claim of the plaintiff was in that carriage, and to make the forward wheels go beneath was simply a change which any mechanic could make and which would naturally suggest itself, if that was the desideratum, to any mechanic looking at the construction of the carriage.

Then, as to the second claim. The plaintiff constructs his wagon with what he calls a fifth wheel, that is, a circular piece of wood, iron, or of any other material, (of course it may be so constructed) passing over hounds 291and on the forward axle, and outside of and concentric with that, what he terms a sixth wheel, which constitutes a sway bar, also passing over the hounds and on the forward axle, and upon which the reach rests as the wagon turns, in the manner suggested by this model, which is a perfect resemblance of the plaintiff's wagon.

The question is, what is the difference between the structure of this and the one which was referred to in the testimony, and which, it was established, has been in existence for fifteen or sixteen years? Of course, what this circular piece of wood, of iron, or of other material is called is immaterial; calling it a sway bar does not change the nature or form of the thing itself, and in that carriage which was constructed long before the plaintiff's there was the equivalent to all intents and purposes, as it seems to me, of what the plaintiff calls the sway bar; that is to say, there was a circular piece of wood or iron. There was in this, which is a representation of the carriage, what the draughts-man has called a sway bar; it, perhaps, may not have been called so by the man who constructed the carriage, but it is clear that it would perform the functions of a sway bar precisely as in the plaintiff's wagon, if the wheels passed beneath the reach, so that the question arose in my mind, and it was the only one about which I had any doubt in the case, whether this could properly be the subject of a patent; whether the invention was of such a character that it could be considered patentable; and on the whole, when comparing it with the carriage already referred to, I could not perceive that there was any material difference in the structure of the two things. In this wagon of the plaintiff, it passes around, the wheels go beneath the reach, and of course, the reach rests upon the sway bar. The same office would be performed by this circular piece of wood or of iron, as the case may be, in the carriage, if the wheels went beneath the reach, and then the only point that could possibly arise was, whether changing the form of the structure of the reach or of the forward wheels of the wagon so as to permit them to go under the reach was a matter of invention and patentable as such, and for the reasons that I have already given it seems to me that it was not, and therefore that the second claim must fail as well as the first.

In looking at this case I am struck with the facility with which patents are obtained, because it would be incomprehensible to me if the officers in the patent office had known of the existence of such a carriage as that which was proved, with the reach as there constructed, they could have granted a patent in such a case as this, and while it is perfectly just that every real, genuine invention devised by any one should be protected; still it is not just to the public that mere changes of form should have the protection of the law. Perhaps there is reason to believe they are not sufficiently rigid on this point in the patent office. It is true that, the officers there being the persons to whom the law in-trusts the examination of inventions and the granting of patents, the courts are liberal in the construction which they give to patents, with a view of protecting any possible right which a party may have. But to allow a person by a mere change in the structure of a machine, such as would suggest itself to any mechanic, to acquire a monopoly for that change, and the shield and protection of the law would be an abuse of the law itself.

The finding in this case will be for the defendant.

1 [Reported by Josiah H. Bissell, Esq., and here reprinted by permission. Merw. Pat. Inv. 193, contains only a partial report.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.