Case No. 4,548.

EUREKA CONSOL. MIN. CO. v. RICHMOND MIN. CO.

[4 Sawy. 302;1 9 Morr. Min. Rep. 578.]

Circuit Court, D. Nevada.

Aug. 22, 1877.2

VEIN AND LODE DEFINED—OBJECTIONS TO PATENT TO MINING CLAIM, WHEN MADE—DOCTRINE OF RELATION NOT APPLICABLE TO MINING PATENT—SILENCE OF FIRST LOCATOR A WAIVER—PROVISION AS TO PARALLEL LINES DIRECTOR?—END LINES TO MINING CLAIM IMPLIED IN ACT OF 1866—PRESUMPTIONS AS TO OFFICIAL DUTIES—LODE MAY BE FOLLOWED ON DIP, NOT ON VEIN BEYOND END OF CLAIM—MINING ACTS OF 1866 AND 1872 CONSTRUED—AGREEMENT CONSTRUED—DIVIDING LINE FOLLOWS DIP.

1. The terms “vein” and “lode” as used by miners, and in the mining acts of congress, are applicable to any zone or belt of mineralized rock lying within boundaries clearly separating it from the neighboring rock.

[Explained in Mt. Diablo Mill & Min. Co. v. Callison, Case No. 9,886. Cited in Richmond Min. Co. v. Rose, 114 U. S. 580, 5 Sup. Ct. 1057; Iron Silver, Min. Co. v. Cheesman, 116 U. S. 533, 6 Sup. Ct. 483; Cheesman v. Shreeve, 40 Fed. 793; Blue Bird Min. Co. v. Largey, 49 Fed. 290; Iron Silver Min. Co. v. Mike & Starr Gold & Silver Min. Co., 143 U. S. 420, 12 Sup. Ct. 551; Book v. Justice Min. Co., 58 Fed. 121. Distinguished in Doe v. Waterloo Min. Co., 54 Fed. 935.]

2. Under the mining acts of congress, where one is seeking a patent for his mining location, and gives the prescribed notice, any, other claimant of an unpatented location objecting to the patent on account of extent, or form, or because of asserted prior location, must come forward with his objections and present them, or he will be afterward precluded from objecting to the issue of the patent.

[Cited in Northern Pac. R. Co. v. Cannon, 54 Fed. 257.]

3. The doctrine of “relation” cannot be applied so as to cut off the rights of the earlier patentee under a later location.

4. The silence of the first locator when a subsequent locator applies for a patent is, under the statute, a waiver of his priority.

5. The provision of the statute of 1872, requiring the lines of each claim to be parallel to each other is merely directory, and no consequence is attached to a deviation from its direction.

6. “End lines” are not named in the act of 1866, but they are necessarily implied in it. By allowing a certain number of feet on a ledge, the mining law meant that a locator might follow his vein for that distance on the course of a ledge, and to any depth within that distance. 14 Stat. 251.

7. The presumption of law is, that the officers charged with the supervision of applications for mining patents, do their duty. If, under any circumstances, a patent for a mining location, issued after the passage of the act of 1872, may be valid without the parallelism of lines required by that act, the law will presume that such circumstances existed.

[Cited in Iron Silver Min. Co. v. Mike & Starr Gold & Silver Min. Co., 143 U. S. 419, 12 Sup. Ct. 550.]

8. The patents allowed by these acts do not authorize the patentee to follow the vein outside of the end lines of the claim vertically drawn down through the lode; but authorize him to follow his vein with its dips, angles and variations to any depth, though it may enter the land lying on the side of the claim. Lines drawn down vertically through the ledge or lode, at right angles with a line representing the course at the ends of the claimant's line of location, will carve out a section of the ledge or lode within which he is permitted to work, and out of which he cannot pass.

9. The act of 1866 allowed so many lineal feet of the particular lode located and surface ground for the convenient working thereof. The act of 1872 granted certain surface ground and the particular lode located and all other lodes, the top or apex of which lies within the surface-lines, subject to the limitation that in following the lodes to any depth, the miner shall be confined to such portions thereof as lie between vertical planes drawn downward through the end lines of his location. The act of 1872 in terms annexes this condition to the possession not only of claims subsequently located, but to the possession of those previously located. 17 Stat. 91.

10. In the case of lode claims, a dividing line between them, fixed by agreement, upon the surface at a given point, or for a given distance, must be extended along the dip of the lode, so far as that goes, and must necessarily divide all that the location on the surface carries, or it

820will not constitute a boundary between the claims.

[See note at end of case.]

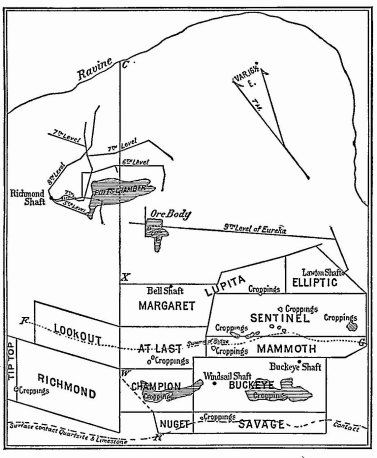

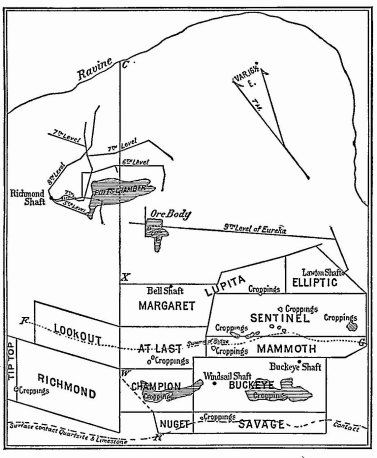

The accompanying diagram represents the surface location of the Champion, At Last, Margaret or Lupita, Nugget, Savage, Buckeye, Mammoth, Sentinel and Elliptic mining claims of the Eureka Company, plaintiff, and of the Richmond, Lookout and Tip-top claims of the Richmond Company, defendant; the Lawton or Eureka shaft, and the ninth level therefrom connecting with ore body D E; the Richmond shaft and levels therefrom, and the Potts chamber from which ore has been taken through the Richmond fifth level; the R W X, described in the agreement, and this line extended to C. The dotted line represents the surface line of contact between the quartizite and limestone. South of this line is a belt of quartzite, and north of it a belt of metamorphosed limestone, and north of this limestone is a belt of shale. The ore bodies are found in the metamorphosed limestone between the quartzite and shale. This belt of limestone bounded by the quartzite and shale extends nearly east and west over one mile, and varies in width from five to eight hundred feet on the surface to from two to four hundred feet at the greatest depth of working, which is about nine hundred feet. The Potts chamber is about five hundred feet below the surface. The quartizite and limestone dip to the northward at an angle of about 45° from the horizon.

In 1873, the Eureka Company, owned the Lookout claim, and the Richmond Company found on the surface in the Richmond claim, and followed down on its dip to the northward under the Lookout surface a large body of ore. The Eureka Company claiming the ore under the Lookout surface, thereupon sued the Richmond Company to determine the title thereto, and in settlement of that litigation an agreement in writing was made on the sixteenth day of June, A. D. 1873, between the plaintiff, the Eureka Consolidated Mining Company, of the first part, and the defendant, the Richmond Mining Company of Nevada, party of the second part, which provided:

“Whereas, differences have arisen, and below exist, between the parties hereto in respect to the ownership and right of possession of certain mining ground, known as the Lookout ground or claimand of the ores, metals and deposits found in and under said ground; and whereas an action is, or certain actions are, now pending in the courts of the state of Nevada, wherein the party hereto of the first part is plaintiff, and the

821party hereto of the second part and others are defendants, for the recovery * * * of the possession of the ground and of the ores therein contained, etc.; and whereas, the said parties have agreed to settle all the differences between them, and put an end to the litigation now pending as aforesaid;

“Now, therefore, this agreement witnesseth, that the said party of the first part, for and in consideration of the sum of $85,000 * * * and the further covenants, agreements, and conditions hereinafter contained * * * has agreed, and does hereby agree, to convey to the said party of the second part, its successors and assigns, with warranty against its own acts, all that certain lot, piece or parcel of land or mining ground * * * known as the Lookout ground or claim; and also all the mining ground and claim lying on the north-westerly side of a certain line, commencing at the north-easterly corner of the (Margaret mining ground or claim, which corner is marked X on the map or plan hereto annexed, and made part of this agreement; running thence in a south-westerly direction along the edge of said Margaret ground, the At Last ground, and the Champion ground, to a point marked W on said map; thence southerly to the north-easterly corner of the Nugget ground; thence in a south-westerly direction along the edge of said Nugget ground, to the north-westerly corner thereof at the point marked R on said map or plan; together with all the ores, precious metalsand all veins, lodes, ledges, deposits, dips, spurs or angles on, in, or under the same contained; and the said party of the first part further agrees not to protest against or put any obstacle in the way of the party of the second part in their application for a United States patent to the Richmond or other lodes or veins, provided such application does not conflict or cross the aforesaid line agreed upon; and the said party of the second part, for the consideration aforesaid, hath further agreed, and doth hereby further argee to convey unto the said party of the first part, with warranty against its own acts, all right, title, or interest in or to any and all the land or mining ground, on the south-easterly side of the line hereinbefore mentioned and laid down on the said map hereto annexed, and in and to all ores, precious metals, veins, lodes, ledges, deposits, dips, spurs and angles on, in or under the said land or mining ground, or any part thereof. It being the object and intention of the said parties hereto to confine the workings of the party of the second part to the northwesterly side of the said line continued downward to the centre of the earth, which line is hereby agreed upon as the permanent boundary line between the claims of the said parties.”

Conveyances were also made in pursuance of this agreement After this agreement and settlement, the defendant followed the ore body found in the Richmond and Lookout claims downward toward the northward on the dip, and eastward on the general course or strike of the underlying quartette and overhanging shale to the Potts chamber, where the body of ore extended eastward across the line W X, produced northward from X to C. The ore body on the line from the Richmond to the Potts chamber varied greatly in size at different points, being alternately contracted or pinched to a small seam, then widening into larger bodies, but there was a continuous connection. The defendant claimed and worked that part of the chamber to the eastward of said line W X produced to C, whereupon the plaintiff claiming that portion of the ore body as being on the dip of its portion of the lode brought this action to recover the possession.

The other facts are sufficiently stated in the opinion of the court.

S. Heydenfeldt, R. S. Mesick, H. K. Mitchell, and Garber & Thornton, for plaintiff.

Thos. Wren, S. M. Wilson, R. M. Clarke, A. M. Hillhouse, C. J. Lansing, Crittenden Thornton, and Williams & Thornton, for defendant.

FIELD, Circuit Justice. This is an action for the possession of certain mining ground, particularly described in the complaint, situated in Eureka mining district, in the county of Eureka, in the state of Nevada. The plaintiff is a corporation created under the laws of California, and the defendant, the Richmond Mining Company, is a corporation created under the laws of Nevada. The other defendants, Thomas Wren and Joseph Potts, are citizens of the latter state. The action was originally commenced in a state court of Nevada, but upon application of the plaintiff, and upon the ground of its incorporation in another state, and the presumed citizenship, from that fact, of its corporators or stockholders in that state, it was transferred to the circuit court of the United States. The complaint in the state court, in addition to the usual allegations of a declaration in ejectment set forth various grounds upon which was based a prayer for an order restraining the defendants from working the premises in controversy pending the action. The defendants, in their answer to the complaint, not only denied the title of the plaintiff, but made various averments upon which a like restraining order against the plaintiff was asked. Both orders were granted. This union of a demand in ejectment for the property in controversy, with a prayer for provisional equitable relief, is permitted by the system of procedure which obtains in the state courts, thus saving the parties the necessity of litigating in two suits what can as readily and less expensively be accomplished in one. But this union is not permitted in the federal courts; and upon the transfer of the present action, the pleadings of the plaintiff were amended, by substituting a regular complaint in ejectment on the law 822 side of the court; and a bill was filed for an injunction on its equity side. The defendants answered both, and also filed a cross-bill for an injunction against the plaintiff.

By arrangement of the parties, the defendants, Messrs. Wren and Potts, are dropped out of the controversy, and their names may be stricken from the pleadings. The claim for damages is also waived in this action, without prejudice to any future proceedings with respect to them. By stipulation, the case at law—the action of ejectment—is tried by the court without the intervention of a jury, and the judges sit at San Francisco, instead of Carson, their finding and judgment to be entered in term time in the latter place as though the case were heard and decided there. The testimony taken in the action at law is to be received as depositions in the equity suit, and both cases are to be disposed of at the same time, to the end that the whole controversy between the parties may be settled at once.

The premises in controversy are of great value, amounting, by estimation, to several hundred thousands of dollars, and the case has been prepared for trial with a care proportionate to this estimate of the value of the property; and the trial has been conducted by counsel on both sides with eminent ability.

Whatever could inform, instruct or enlighten the court, has been presented by them. Practical miners have given us their testimony as to the location and working of the mine. Men of science have explained to us how it was probable that nature, in her processes, had deposited the mineral where it is found. Models of glass have made the hill, where the mining ground lies, transparent, so that we have been able to trace the course of the veins, and see the chambers of ore found in its depths. For myself, after a somewhat extended judicial experience, covering now a period of nearly twenty years, I can say that I have seldom, if ever, seen a case involving the consideration of so many and varied particulars, more thoroughly prepared or more ably presented. And what has added a charm to the whole trial has been the conduct of counsel on both sides, who have appeared to assist each other in the development of the facts of the case, and have furnished an illustration of the truth that the highest courtesy is consistent with the most earnest contention.

The mining ground which forms the subject of controversy is situated in a hill known as “Ruby Hill,” a spur of Prospect mountain, distant about two miles from the town of Eureka, in Nevada. Prospect mountain is several miles in length, running in a northerly and southerly course. Adjoining its northerly end is this spur called “Ruby Hill,” which extends thence westerly, or in a southwesterly direction. Along and through this hill, for a distance slightly exceeding a mile, is a zone of limestone, in which, at different places throughout its length, and in various forms, mineral is found, this mineral appearing sometimes in a series or succession of ore bodies more or less closely connected, sometimes in apparently isolated chambers, and at other times in what would seem to be scattered grains. And our principal inquiry is to ascertain the character of this zone, in order to determine whether it is to be treated as constituting one lode, or as embracing several lodes, as that term is used in the acts of congress of 1866 and 1872, under which the parties have acquired whatever rights they possess. In this inquiry, the first thing to be settled is the meaning of the term in those acts. This meaning being settled, the physical characteristics and the distinguishing features of the zone will be considered.

Those acts give no definition of the term. They use it always in connection with the term “vein.” The act of 1866 provided for the acquisition of a patent by any person or association of persons claiming “a vein or lode of quartz, or other rock in place, bearing gold, silver, cinnabar or copper.” The act of 1872 speaks of veins or lodes of quartz or other rock in place, bearing similar metals or ores. Any definition of the term should, therefore, be sufficiently broad to embrace deposits of the several metals or ores here mentioned. In the construction of statutes, general terms must receive that interpretation which will include all the instances enumerated as comprehended by them. The definition of a “lode” given by geologists is, that of a fissure in the earth's crust filled with mineral matter, or more accurately, as aggregations of mineral matter containing ores in fissures. See Von Cotta's Treatise on Ore Deposits, Prime's Translation, 26. But miners used the term before geologists attempted to give it a definition. One of the witnesses in this case, Dr. Raymond, who for many years was in the service of the general government as commissioner of mining statistics, and in that capacity had occasion to examine and report upon a large number of mines in the states of Nevada and California, and the territories of Utah and Colorado, says that he has been accustomed, as a mining engineer, to attach very little importance to those cases of classification of deposits which simply involve the referring of the subject back to verbal definitions in the books. The whole subject of the classification of mineral deposits he states to be one in which the interests of the miner have entirely overridden the reasonings of the chemists and geologists. “The miners,” to use his language, “made the definition first. As used by miners, before being defined by any authority, the term ‘lode’ simply meant that formation by which the miner could be led or guided. It is an alteration of the verb ‘lead;’ and whatever the miner could follow, expecting to find ore, was his lode. Some formation within which he could find ore, and out of which he could not expect to find 823 ore, was his lode.” The term “lode-star,” “guiding-star,” or “north star,” he adds, is of the same origin. Cinnabar is not found in any fissure of the earth's crust, or in any lode, as defined by geologists, yet the acts of congress speak, as already seen, of lodes of quartz, or rock in place, bearing cinnabar. Any definition of “lode,” as there used, which did not embrace deposits of cinnabar, would be as defective as if it did not embrace deposits of gold or silver. The definition must apply to deposits of all the metals named, if it apply to a deposit of any one of them. Those acts were not drawn by geologists or for geologists; they were not framed in the interests of science, and consequently with scientific accuracy in the use of terms. They were framed for the protection of miners in the claims which they had located and developed, and should receive such a construction as will carry out this purpose. The use of the terms “vein” and “lode” in connection with each other in the act of 1866, and their use in connection with the term “ledge” in the act of 1872, would seem to indicate that it was the object of the legislator to avoid any limitation in the application of the acts, which a scientific definition of any one of these terms might impose.

It is difficult to give any definition of the term as understood and used in the acts of congress, which will not be subject to criticism. A fissure in the earth's crust, an opening in its rocks and strata made by some force of nature, in which the mineral is deposited, would seem to be essential to the definition of a lode, in the judgment of geologists. But to the practical miner, the fissure and its walls are only of importance as indicating the boundaries within which he may look for and reasonably expect to find the ore he seeks. A continuous body of mineralized rock lying within any other well-defined, boundaries on the earth's surface and under it, would equally constitute, in his eyes, a lode. We are of opinion, therefore, that the term as used in the acts of congress is applicable to any zone or belt of mineralized rock lying within boundaries clearly separating it from the neighboring rock. It includes, to use the language cited by counsel, all deposits of mineral matter found through a mineralized zone or belt coming from the same source, impressed with the same forms, and appearing to have been created by the same processes.

Examining, now, with this definition in mind, the features of the zone which separate and distinguish it from the surrounding country, we experience little difficulty in determining its character. We find that it is contained within clearly defined limits, and that it bears unmistakable marks of originating, in all its parts, under the influence of the same creative forces. It is bounded on the south side for its whole length, at least so far as explorations have been made, by a wall of quartzite of several hundred feet in thickness; and on its north side, for a like extent, by a belt of clay, or shale, ranging in thickness from less than an inch to seventy or eighty feet At the east end of the zone, in the Jackson mine, the quartzite and shale approach so closely as to be separated by a bare seam, less than an inch in width. From that point they diverge, until, on the surface in the Eureka mine, they are about five hundred feet apart, and on the surface in the Richmond mine, about eight hundred feet. The quartzite has a general dip to the north, at an angle of about forty-five degrees, subject to some local variations, as the course changes. The clay or shale is more perpendicular, having a dip at an angle of about eighty degrees. At some depth under the surface, these two boundaries of the limestone, descending at their respective angles, may come together. In some of the levels worked, they are now only from two to three hundred feet apart.

The limestone found between these two limits—the wall of quartzite and the seam of clay or shale—has, at some period of the world's history, been subjected to some dynamic force of nature, by which it has been broken up, crushed, disintegrated, and fissured in all directions, so as to destroy, except in places of a few feet each, so far as explorations show, all traces of stratification; thus specially fitting it, according to the testimony of the men of science, to whom we have listened, for the reception of the mineral which, in ages past, came up from the depths below in solution, and was deposited in it Evidence that the whole mass of limestone has been, at some period, lifted up and moved along the quartzite, is found in the marks of attrition engraved on the rock. This broken, crushed and fissured condition pervades, to a greater or less extent, the whole body, showing that the same forces which operated upon a part, operated upon the whole, and at the same time. Wherever the quartzite is exposed, the marks of attrition appear. Below the quartzite no one has penetrated. Above the shale the rock has not been thus broken and crushed. Stratification exists there. If in some isolated places there is found evidence of disturbance, that disturbance has not been sufficient to affect the stratification. The broken, crushed and fissured condition of the limestone gives it a specific, individual character, by which it can be identified and separated from all other limestone in the vicinity.

In this zone of limestone numerous caves or chambers are found, further distinguishing it from the neighboring rock. The limestone being broken and crushed up as stated, the water from above readily penetrated into it, and, operating as a solvent, formed these caves and chambers. No similar cavities are found in the rock beyond the shale, its hard and unbroken character not permitting, or at least opposing such action from the water above.

824Oxide of iron is also found in numerous places throughout the zone, giving to the miner assurance that the metal he seeks is in its vicinity.

This broken, crushed and fissured condition of the limestone, the presence of the oxides of iron, the caves or chambers we have mentioned, with the wall of quartette and seam of clay bounding it, give to the zone, in the eyes of the practical miner, an individuality, a oneness as complete as that which the most perfect lode in a geological sense ever possessed. Each of the characteristics named, though produced at a different period from the others, was undoubtedly caused by the same forces operating at the same time upon the whole body of the limestone.

Thoughout this zone of limestone, as we have already stated, mineral is found in the numerous fissures of the rock. According to the opinions of all the scientific men who have been examined, this mineral was brought up in solution from the depths of the earth below, and would therefore naturally be very irregularly deposited in the fissures of the crushed matter, as these fissures are in every variety of form and size, and would also find its way in minute particles in the loose material of the rock. The evidence shows that it is sufficiently diffused to justify giving to the limestone the general designation of mineralized matter—metal-bearing rock. The three scientific experts produced by the plaintiff, Mr. Keyes, Mr. Raymond and Mr. Hunt, all of them of large experience and extensive attainments, and two of them of national reputation, have given it as their opinion, after examining the ground, that the zone of limestone between the quartzite and the shale constitutes one “vein” or “lode,” in the sense in which those terms are used by miners. Mr. Keyes, who for years was superintendent of the mine of the plaintiff, concludes a minute description of the character and developments of the ground, by stating that in his judgment, according to the customs of miners in this country and common sense, the whole of that space should be considered and accepted as a lead, lode, or ledge of metal-bearing rock in place.

Dr. Raymond, after giving a like extended account of the character of the ground, and his opinion as to the causes of its formation, and stating with great minuteness the observations he had made, concludes by announcing as his judgment, after carefully weighing all that he had seen, that the deposit between the quartzite and the shale is to be considered as a single “vein” in the sense in which the word is used by miners—that is, as a single ore deposit of identical origin, age and character throughout.

Dr. Hunt, after stating the result of his examination of the ground and his theory as to the formation of the mine, gives his judgment as follows: “My conclusion is this: That this whole mass of rock is impregnated with ore; that although the great mass of ore stretches for a long distance above horizontally and along an incline down the foot wall, as I have traced it, from this deposit you can also trace the ore into a succession of great cavities or bonanzas lying irregularly across the limestone and into smaller caverns or chasms of the same sort; and that the whole mass of the limestone is irregularly impregnated with the ore. I use the word ‘impregnation’ in the sense that it has penetrated here and there; little patches and stains, ore-vugs and caverns and spaces of all sizes and all shapes, irregularly disseminated through the mass. I conclude, therefore, that this great mass of ore is, in the proper sense of the word, a great ‘lode,’ or a great ‘vein,’ in the sense in which the word is used by miners; and that practically the only way of utilizing this deposit, is to treat the whole of it as one great ore-bearing lode or mass of rock.”

This conclusion as to the zone constituting one lode of rock-bearing metal, it is true, is not adopted by the men of science produced as witnesses by the defendant, the Richmond Company. These latter gentlemen, like the others, have had a large experience in the examination of mines, and some of them have acquired a national reputation for their scientific attainments. No one questions their learning or ability, or the sincerity with which they have expressed their convictions. They agree with the plaintiff's witnesses as to the existence of the mineralized zone of limestone with an underlying quartzite and an overlying shale; as to the broken and crushed condition of the limestone, and substantially as to the origin of the metal and its deposition in the rock. In nearly all other respects they disagree. In their judgment, the zone of limestone has no features of a lode. It has no continuous fissure, says Mr. King, to mark it as a lode. A lode, he adds, must have a foot-wall and a hanging-wall, and if it is broad, these must connect at both ends, and must connect downward. Here, there is no hanging-wall or foot-wall; the limestone only rests as a matter of stratigraphical fact on underlying quartzite, and the shale overlies it. And distinguishing the structure at Ruby hill from the Comstock lode, the same witness says that the one is a series of sedimentary beds laid down in the ocean and turned up; the other is a fissure extending between two rocks.

The other witnesses of the defendant, so far as they have expressed any opinion as to what constitutes a lode, have agreed with the views of Mr. King. It is impossible not to perceive that these gentlemen at all times carried in their minds the scientific definition of the term as given by geologists, that a lode is a fissure in the earth's crust filled with mineral matter, and disregarded the broader, though less scientific, definition of the miner who applies the term to all zones or belts of metal-bearing rock lying 825 within clearly marked boundaries. For the reasons already stated, we are of opinion that the acts of congress use the term in the sense in which miners understand it.

If the scientific definition of a lode, as given by geologists, could be accepted as the only proper one in this case, the theory of distinct veins existing in distinct fissures of the limestone would be not only plausible, but reasonable; for that definition is not met by the conditions in which the Eureka mineralized zone appears. But as that definition cannot be accepted, and the zone presents the case of a lode as that term is understood by miners, the theory of separate veins, as distinct and disconnected bodies of ore falls to the ground. It is, therefore, of little consequence what name is given to the bodies of ore in the limestone, whether they be called pipe veins, rake veins or pipes of ore, or receive the new designation suggested by one of the witnesses, they are but parts of one greater deposit, which permeates, in a greater or less degree, with occasional intervening spaces of barren rock, the whole mass of limestone, from the Jackson mine to the Richmond, inclusive.

The acts of congress of 1866 and 1872 dealt with a practical necessity of miners; they were passed to protect locations on “veins” or “lodes,” as miners understood those terms. Instances without number exist where the meaning of words in a statute has been enlarged or restricted and qualified to carry out the intention of the legislature. The inquiry, where any uncertainty exists, always is as to what the legislature intended, and when that is ascertained it controls. In a recent case before the supreme court of the United States, singing birds were held not to be live animals, within the meaning of a revenue act of congress. Reiche v. Smythe, 13 Wall. [80 U. S.] 162. And in a previous case, arising upon the construction of the Oregon donation act of congress, the term, “a single man,” was held to include in its meaning an unmarried woman. Silver v. Ladd, 7 Wall. [74 U. S.] 219. If any one will examine the two decisions, reported as they are in Wallace's Reports, he will find good reasons for both of them.

Our judgment being that the limestone zone in Ruby hill, in Eureka district, lying between the quartzite and the shale, constitutes, within the meaning of the acts of congress, one lode of rock bearing metal, we proceed to consider the rights conveyed to the parties by their respective patents from the United States. All these patents are founded upon previous locations, taken up and improved according to the customs and rules of miners in the district. Each patent is evidence of a perfected right in the patentee to the claim conveyed, the initiatory step for the acquisition of which was the original location. If the date of such location be stated in the instrument or appear from the record of its entry in the local land-office, the patent will take effect by relation as of that date, so far as may be necessary to cut off all intervening claimants, unless the prior right of the patentee, by virtue of his earlier location, has been lost by a failure to contest the claim of the intervening claimant, as provided in the act of 1872. As in the system established for the alienation of the public lands, the patent is, the consummation of a series of acts, having for their object the acquisition of the title, the general rule is to give to it an operation by relation at the date of the initiatory step, so far as may be necessary to protect the patentee against subsequent claimants to the same property. As was said by the supreme court in the case of Shepley v. Cowan, 91 U. S. 338, where two parties are contending for the same property, the first in time, in the commencement of proceedings for the acquisition of the title, when the same are regularly followed up, is deemed to be the first in right.

But this principle has been qualified in its application to patents of mining ground, by provisions in the act of 1872, for the settlement of adverse claims before the issue of the patent Under that act, when one is seeking a patent for his mining location and gives proper notice of the fact as there prescribed, any other claimant of an unpatented location objecting to the patent of the claim, either on account of its extent or form, or because of asserted prior location, must come forward with his objections and present them, or he will afterwards be precluded from objecting to the issue of the patent. While, therefore, the general doctrine of relation applies to mining patents so as to cut off intervening claimants, if any there can be, deriving title from other sources, such perhaps as might arise from a subsequent location of school warrants or a subsequent purchase from the state, as in the case of Heydenfeldt v. Daney Gold & Silver Min. Co., 93 U. S. 634, the doctrine cannot be applied so as to cut off the rights of the earlier patentee, under a later location where no opposition to that location was made under the statute. The silence of the first locator is, under the statute, a waiver of his priority.

But from the view we take of the rights of the parties under their respective patents, and the locations upon which those patents were issued, the question of priority of location is of no practical consequence in the case.

The plaintiff is the patentee of several locations on the Ruby hill lode, but for the purpose of this action it is only necessary to refer to three of them—the patents for the Champion, the At Last, and the Lupita or Margaret claims. The first of these patents was issued in 1872, the second in 1876, and the third in 1877. Within the end lines of the locations, as patented in all these cases, when drawn down vertically through the lode, the property in controversy falls. Objection 826 is taken to the validity of the last two patents, because the end lines of the surface locations patented are not parallel, as required by the act of 1872. But to this objection there are several obvious answers. In the first place, it does not appear upon what locations the patents were issued. They may have been, and probably were, issued upon locations made under the act of 1866, where such parallelism in the end lines of the surface locations was not required. The presumption of the law is, that the officers of the executive department, specially charged with the supervision of applications for mining patents and the issue of such patents, did their duty; and in an action of ejectment, mere surmises to the contrary will not be listened to. If, under any possible circumstances, a patent for a location without such parallelism may be valid, the law will presume that such circumstances existed. A patent of the United States for land, whther agricultural or mineral, is something upon which its holder can rely for peace and security in his possessions. In its potency it is ironclad against all mere speculative inferences. In the second place, the provision of the statute of 1872, requiring the lines of each claim to be parallel to each other, is merely directory, and no consequence is attached to a deviation from its direction. Its object is to secure parallel end lines drawn vertically down, and that was effected in these cases by taking the extreme points of the respective locations on the length of the lode. In the third place, the defect alleged does not concern the defendant, and no one but the government has the right to complain.

The defendant, the Richmond Mining Company, also holds several patents issued to it upon different locations; but in this case it specially relies upon the patents of the Richmond and Tip-top claims. It is alleged that these patents were issued upon locations made earlier than any upon which the patents to the plaintiff were issued. Assuming this to be the fact, and claiming from it that the patents, by relation back to such locators, antedate in their operation the patents of the plaintiff; and the further fact that the locations were made under the act of 1866, the defendant relies, upon the facts assumed, to defeat the pretensions of the plaintiff. It contends that, inasmuch as the croppings of the vein it works are within the surface of its patented locations, it can follow the vein wherever it leads, though it be outside of the end lines of the locations when vertically drawn down through the lode. Its position is that, whenever under the law of 1866 a location was made on a lode or vein, a right was acquired to follow the vein wherever it might lead, without regard to the end lines of the location. This position is urged with great persistence by one of the counsel of the defendant, and with the ability which characterizes all his discussions.

The second section of the act of 1866, upon the provisions of which this position is based, provides: “That whenever any person, or association of persons, claims a vein or lode of quartz, or other rock in place, bearing gold, silver, cinnabar or copper, having previously occupied and improved the same according to local customs or rules of miners in the district where the same is situated, and having expended, in actual labor and improvements thereon, an amount of not less than one thousand dollars, and in regard to whose possession there is no controversy or opposing claim, it shall and may be lawful for said claimant, or association of claimants, to file in the local land-office a diagram of the same, so extended, laterally or otherwise, as to conform to the local laws, customs and rules of miners, and to enter such tract and receive a patent therefor, granting such mine, together with the right to follow such vein or lode, with its dips, angles and variations, to any depth, although it may enter the land adjoining, which land adjoining shall be sold subject to this condition.”

It will be seen by this section that, to entitle a party to a patent, his claim must have been occupied and improved, according to the local customs or rules of miners of the district, and that his diagram of the same, filed in the land-office, in its extension laterally or otherwise, must be in conformity with them.

The rules of the miners in the Eureka mining district, adopted in 1865—laws of the district, as they are termed by the miners—provided that claims of mining ground should be made by posting a written notice on the claimant's ledge, defining its boundaries, if possible; that each claim should consist of two hundred feet on the ledge, but claimants might consolidate their claims by locating in a common name, if, in the aggregate, no more ground was claimed than two hundred feet for each name, and that each locator should be entitled to all the dips, spurs and angles connecting with his ledge; and that a record of all claims should be made within ten days from the date of location. The rules also allowed claimants to hold one hundred feet each side of their ledge for mining and building purposes, but declared that they should not be entitled to any other ledge within this surface.

It will be perceived by these rules that they had reference entirely to locations of claims on ledges. It would seem that the miners of the district then supposed that the mineral in the district was only found in veins or ledges, and not in isolated deposits. In February, 1869, new rules were added to those previously passed, authorizing the location of such deposits. These new rules provided that each deposit claim should consist of one hundred feet square, and that the location should take all the mineral within the ground to any depth.

Under these rules, square locations and linear 827 locations were made by parties, through whom the defendant derives title on what is called the Richmond ledge, and linear locations were made on what is called the Tiptop ledge, with surface locations for mining purposes, both parties claiming with their locations all dips, spurs and angles. It is only of the linear locations we have occasion to speak; it is under them that the defendant asserts title to the premises in controversy.

Now, as neither the rules of miners in Eureka mining district nor the act of 1866, in terms, speak of end lines to locations made on ledges, nor in terms impose any limitation upon miners following these veins wherever they may lead, it is contended that no such limitation can be considered as having existed and be enforced against the defendant. The act of 1866, it is, said, recognizes the right of the locator to follow his vein outside of any end lines drawn vertically down when it permits him to obtain a patent granting his mine, “together with the right to follow such vein or lode with its dips, angles and variations to any depth, although it may enter the land adjoining, which land adjoining shall be sold subject to this condition.”

It is true that end lines are not in terms named in the rules of the miners, but they are necessarily implied, and no reasonable construction can be given to them without such implication. What the miners meant by allowing a certain number of feet on a ledge was that each locator might follow his vein for that distance on the course of the ledge, and to any depth within that distance. So much of the ledge he was permitted to hold as lay within vertical planes drawn down through the end lines of his location, and could be measured anywhere by the feet on the surface. If this were not so, he might by the bend of his vein hold under the surface along the course of the ledge double and treble the amount he could take on the surface. Indeed, instead of being limited by the number of feet prescribed by the rules, he might in some cases oust all his neighbors and take the whole ledge. No construction is permissible which would substantially defeat the limitation of quantity on a ledge, which was the most important provision in the whole system of rules.

Similar rules have been adopted in numerous mining districts, and the construction thus given has been uniformly and everywhere followed. We are confident that no other construction has ever been adopted in any mining district in California or Nevada. And the construction is one which the law would require in the absence of any construction by miners. If, for instance, the state were to-day to deed a block in the city of San Francisco to twenty persons, each to take twenty feet front, in a certain specified succession, each would have assigned to him by the law a section parallel with that of his neighbor of twenty feet in width, cut through the block. No other mode of division would carry out the grant.

The act of 1866 in no respect enlarges the right of the claimant beyond that which the rules of the mining district gave him. The patent which the act allows him to obtain does not authorize him to go outside of the end lines of his claim, drawn down vertically through the ledge or lode. It only authorizes him to follow his vein with its dips, angles and variations, to any depth, although it may enter land adjoining—that is, land lying beyond the area included within his surface lines. It is land lying on the side of the claim, not on the ends of it, which may be entered. The land on the ends is reserved for other claimants to explore. It is true, as stated by the defendant, that the surface land taken up in connection with a linear location on the ledge or lode is, under the act of 1866, intended solely for the convenient working of the mine, and does not measure the miner's right, either to the linear feet upon its course, or to follow the dips, angles and variations of the vein, or control the direction he shall take. But the line of location taken does measure the extent of the miner's right. That must be along the general course or strike, as it is termed, of the ledge or lode. Lines drawn vertically down through the ledge or lode, at right angles with a line representing this general course at the ends of the claimant's line of location, will carve out, so to speak, a section of the ledge or lode, within which he is permitted to work, and out of which he cannot pass.

As the act of 1866 requires the applicant for a patent to file in the local office a diagram of his claim, such diagram must necessarily present something more than the mere linear location. It is intended that it should embrace the surface claimed for the working of the mine. In this way each of the patents of the parties embraces one or more acres and the fraction of an acre of surface ground and some hundred linear feet on the lode.

The act of 1872 preserves to the miner the rights acquired under the act of 1866, and confers upon him additional rights. Under the act of 1866, he could only hold one lode or vein, although more than one appeared within the lines of his surface location. The surface ground was allowed him for the convenient working of the lode or vein located, and for no other purpose; it conferred no right to any other lode or vein. But the act of 1872 alters the law in this respect; it grants to him the exclusive right of possession to a quantity of surface ground not exceeding a specified amount, and not only to the particular lode or vein located, but to all other veins, lodes and ledges, the top or apex of which lies within the surface lines of his location, with the right to follow such veins; lodes or ledges to any depth. But these additional rights are granted subject 828 to the limitation that in following the veins, lodes or ledges, the miner shall he confined to such portions thereof as lie between vertical planes drawn downward through the end lines of his location, and a further limitation upon his right in cases where two or more veins intersect or cross each other. The act in terms annexes these conditions to the possession not only of claims subsequently located, but to the possession of those previously located. This fact, taken in connection with the reservation of all rights acquired under the act of 1866, indicates that in the opinion of the legislature no change was made in the rights of previous locators by confining their claims within the end lines. The act simply recognized a pre-existing rule applied by miners to a single vein or lode of the locator, and made it applicable to all veins or lodes found within the surface lines.

Our opinion, therefore, is that both the defendant and the plaintiff, by virtue of their respective patents, whether issued upon locations under the act of 1866, or under the act of 1872, were limited to veins or lodes lying within planes drawn vertically downward through the end lines of their respective locations; and that each took the ores found within those planes at any depth in all veins or lodes, the apex or top of which lay within the surface lines of its locations.

The question of priority of location is therefore, as already stated, of no practical importance in the case. This question can only be important where the lines of one patent overlap those of another patent. Here neither the plaintiff nor defendant could pass outside of the end lines of its own locations, whether they were made before or after those upon which the other party relies. And inasmuch as the ground in dispute lies within planes drawn vertically downward through the end lines of the plaintiff's patented locations, our conclusion is that the ground is the property of the plaintiff, and that judgment must be for its possession in its favor.

The same conclusion would be reached if we looked only to the agreement of the parties made on the sixteenth of June, 1873. At that time the plaintiff owned the patented claim called the Lookout claim, adjoining on the north the Richmond claim. The defendant had worked down from an incline in the Richmond and Tip-top into the ore under the surface lines of the Lookout patent. The plaintiff thereupon brought an action for the recovery of the ground and the ores taken from it. A compromise and settlement followed which are contained in an agreement of that date, and were carried out by an exchange of deeds. A map or plat was made showing the different claims held by the two parties. A line was drawn upon this map, on one side of which lay the Champion, the At Last and the Margaret claims, and on the other side lay the Richmond and the Lookout claims. By the agreement of the parties, the plaintiff on the one hand, was to convey to the defendant the Lookout ground, and also all the mining ground lying on the north-westerly side of the line designated, with the ores, precious metals, veins, lodes, ledges, deposits, dips, spurs or angles, on, in or under the same, and to dismiss all pending actions against the defendant; and on the other hand, the defendant was to pay to the plaintiff the sum of $85,000, and to convey, with warranty, against its own acts, all its right, title or interest, in and to all the mining ground situated in the Eureka mining district, on the south-easterly side of the designated line, and in and to all ores, precious metals, veins, lodes, ledges, deposits, dips, spurs or angles, on, in or under the same. “It being,” says the agreement, “the object and intention of the said parties hereto to confine the workings of the party of the second part (the Richmond Mining Company), to the north-westerly side of the said line continued downward to the centre of the earth, which line is hereby agreed upon as the permanent boundary line between the claims of the said parties.”

The deeds executed between the parties the same day were in accordance with this agreement. The deed of the Richmond Mining Company to the plaintiff conveyed all the mining ground lying on the south-easterly side of the designated line, “together with all the dips, spurs and angles, and also all the metals, ores, gold and silver-bearing quartz, rock and earth therein, and all the rights, privileges and franchises thereto incident, appendant and appurtenant or therewith usually had and enjoyed.”

The line thus designated extended down in a direct line along the dip of the lode would cut the Potts chamber, and give the ground in dispute to the plaintiff. That it must be so extended necessarily follows from the character of some of the claims it divides. As the Richmond and the Champion were vein or lode claims, a line dividing them must be extended along the dip of the vein or lode, so far as that goes, or it will not constitute a boundary between them. All lines dividing claims upon veins or lodes necessarily divide all that the location on the surface carries, and would not serve as a boundary between them if such were not the case. The plaintiff would, therefore, be the owner of the ground in dispute by the deed of the defendant, even if it could not assert such ownership solely upon its patented locations. Our finding, therefore, is for the plaintiff, and judgment must be entered thereon in its favor for the possession of the premises in controversy.

[NOTE. The Richmond Mining Company took an appeal and writ of error in these cases, and the decision was affirmed by the supreme court. Richmond Min. Co. v. Eureka Consol. Min. Co., 103 U. S. 839. That court held that the rights of the parties were conclusively fixed by the compromise agreement of June 16, 1873. Referring to the line of division established by that agreement, Mr. Justice Waite, delivering the opinion of the court, said:

829[“In establishing this line it is to be presumed that the parties had in view the peculiar character of the property about which they had been contending. They were settling, as between themselves, their rights to mining property and for the purpose of carrying on mining operations in that locality. They must have known perfectly well, from the observations they had already made, that but a small part of the immense mineral deposit in that zone would probably be found between the exposed surface of the limestone and the quartzite immediately underneath. What they wanted was to fix as between themselves their rights in following what is called in the findings ‘the zone of metamorphosed limestone,’ so as to reach the anticipated deposits in the depths below. A compromise which only settled their controversies to what was directly under the surface would not have accomplished this. The Richmond wanted to be relieved from all embarrassments in getting under the Lookout, and it is to be presumed the Eureka wanted similar privileges under the surface for the Champion and its other claims. For this purpose the parties had to secure the necessary grants from the United States, and the fair inference from what was done is that the Eureka was not to be interfered with in getting what it could on the south and east of the line, and the Richmond was to have the same privilege on the north and west.

[“The language used is to be construed with reference to the peculiar property about which the parties were contracting. Whether the limestone was or was not, within the meaning of the acts of congress and the understanding of miners, a single vein, lode, or ledge, it was all mineralized or metal-bearing rock, as distinguished from the barren walls in which it was inclosed. It descended into the earth on an angle, and, unless parties in working it could follow its course as it went down, they could not avail themselves, to the full extent, of the wealth it contained. When, therefore, we find parties contending about their rights to its possession, and finally agreeing on a line of division between themselves which shall be continued downward towards the center of the earth, the conclusion is irresistible that the line was to be extended downward through the property in its course towards the center of the earth. Anything less than this would make their settlement a mere temporary expedient to get rid of a present difficulty, and leave their most important rights as much in dispute as ever. Such we cannot believe was the understanding.”

[For further proceedings had in the circuit court pending rue appeal, see Case No. 4,549.]

1 [Reported by L. S. B. Sawyer, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

2 [Affirmed in 103 U. S. 839.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

Google.