Case No. 4,505.

EPPINGER v. RICHEY et al.

[14 Blatchf. 307; 3 Ban. & A. 69; 12 O. G. 714; Merw. Pat Inv. 221; 23 Int. Rev. Rec. 319.]1

District Court, S. D. New York.

Sept. 11, 1877.

PATENTS—VALIDITY—PATENTABLE INVENTION—NOVELTY.

1. The letters patent granted to Isaac Eppinger, June 17th, 1873, for an “improvement in plug and bunch tobacco,” are valid.

[Cited in Hat-Sweat Manuf'g Co. v. Davis Sewing Mach. Co., 32 Fed. 403.]

2. The claim of said patent namely, “Plug or bunch tobacco made as herein described, the same consisting of a rope or strand, composed of a sweetened or prepared filler, inclosed in a binder, in turn enveloped in a wrapper, the said rope being coiled around a central core, forming a continuous part of the rope, and the bunch thus made being subjected to a pressure,

742as and for the purposes set forth,” claims a patentable invention.

3. The peculiarity of the invention is in the form and shape of the coil, and the change required invention, and the article produced is a new and useful article of manufacture.

[Cited in Washburn & Moen Manuf&g Co. v. Haish, 4 Fed. 908; Hill v. Biddle, 27 Fed. 561; Asmus v. Alden, Id. 687.]

[This was a suit by Isaac Eppinger against Henry A. Richey and John J. Boniface for the alleged infringement of letters patent No. 140,020, granted to claimant June 17, 1873.]

Benjamin F. Lee, for plaintiff.

Samuel J. Glassey, for defendants.

SHIPMAN, District Judge. This is a bill in equity to restrain the defendants from the infringement of letters patent, dated June 17th, 1873, for an “improvement in plug and bunch tobacco.” The infringement is admitted. The novelty of the alleged invention and its patentability are denied.

Licorice, or some other moist and sweet substance, is used in the manufacture of plug or bunch chewing tobacco, in order to impart moisture and sweetness to the manufactured article. The preservation of these two qualities is greatly desired by the consumer. When tobacco is thus prepared, there is danger that the moist tobacco, if exposed to the air, will ferment, or will mould and “dry rot.” It is, therefore, important to make the plug or bunch as compact as possible, in order to preserve moisture and to prevent mould. Before the date of the invention, this kind of chewing tobacco was made by enclosing strands of sweetened “filler” tobacco in a binder. The wrapped tobacco was then spun upon a wheel, or twirled or rolled by hand into a roll, and, after being encased in a wrapper, was coiled and packed for market, or was subjected to extreme heat, and afterwards to pressure, before being put up in packages. Moisture was removed by this “hot house” process, and thus danger of fermentation was obviated, but the quality of the tobacco was made inferior. Another method of manufacture was by encasing the sweetened filler strands in an unsweetened binder, and, also, in a wrapper. The rope was then bent and braided, and the two ends of the braid were fastened by a cap of wrapper tobacco. The braids were subjected to sidewise pressure, but could not be subjected to pressure endwise, in consequence of their shape, and, therefore, were not compressed sufficiently to exclude the air, and the tobacco was liable to become mouldy. Each braid soon became quite dry in the pocket of the consumer, and lost its flavor.

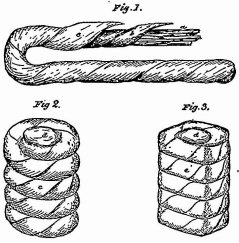

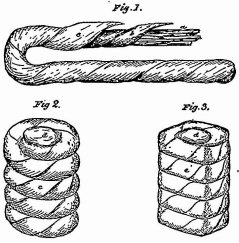

The patentee gives, in his specification, the following description of the patented improvement: “My improved mode of manufacturing plug or bunch tobacco, of the kind above stated, consists in forming the strand of ‘filler’ tobacco, which is treated with licorice or other sweetening substance, in the usual manner. I envelope this filler in a ‘binder,’ which is a brighter and larger leaf, and around the binder I wrap what is called a ‘bright wrapper leaf,’ which is used in its natural condition, without treatment. The rope thus formed is, in fact, a long flexible cigar, with a sweetened filler. It is dry and clean on the exterior, the binder effectually isolating and separating the filler from the exterior wrapper. It does not require to be sweated, and it can be shipped and transported for long distances by water or land conveyance, without danger of moulding or spoiling. The wrapper is of little use for chewing purposes. Therefore, in order to make good chewing tobacco, the filler and binder should be of such proportions to the wrapper, that, while the wrapper will suffice as a protector and preserver of the filler, there will be no appreciable loss in the plug or bunch, for chewing purposes. In Figure 1 is shown a rope or strand such as I have described, a being the filler, b the binder, and c the wrapper. The rope or strand thus made is coiled into a bunch around a central core, one end of the rope, either single or doubled, serving for the core, and the remainder of the length being coiled around this core, as represented in Fig. 2, the central core d and external coil e being thus in one piece, and constituting part of the same continuous strand or rope. The coil or bunch thus made by hand is not, however, completed, nor is it fit for sale or use, being loose and unfinished in appearance and condition. The next step is to finish it, which is effected in the polishing-pot or finisher—a strong receptacle of suitable shape and size to contain a number of plugs, provided with a follower forced down upon the plug or plugs in the pot by hydrostatic pressure or other sufficiently powerful agency. The bunches are first placed in the pots on end, and the follower is then forced down with great pressure upon them. After being allowed to set for about twenty minutes, the followers removed 743 and the bunches are taken out and replaced in the pot on their sides, and side by side, and pressed again in like manner. They can then be pressed on their edges, but this, however, is optional, and not absolutely necessary, as the two pressings have compacted and solidified the plug sufficiently for all ordinary purposes. The plug thus compacted is represented in Fig. 3, and is ready for packing. In conclusion, I wish to state that I do not here broadly claim plug or bunch tobacco put up in coils with a central core and then subjected to pressure; nor do I claim, separately, the combination of a filler, binder and wrapper.” The claim of the patent is for “plug or bunch tobacco made as herein described, the same consisting of a rope or strand, composed of a sweetened or prepared filler, inclosed in a binder, in turn enveloped in a wrapper, the said rope being coiled around a central core, forming a continuous part of the rope, and the bunch thus made being subjected to a pressure, as and for the purposes set forth.”

The advantages of this improved or new article of manufacture are very marked. The moisture of the tobacco is preserved. Air and dampness are excluded by the compactness into which the tobacco is pressed. It can be shipped to warm or damp climates without liability to deterioration by mould, and a single coil can be carried in the pocket of the consumer without becoming dry or friable. The article has had a very large sale, and has commanded a much higher price than the same quality of tobacco when put up in any other form. The price of the patented article has been 51 or 52 cents per pound, exclusive of government tax, while the same qualities of twist or braid tobacco are sold at 27 cents per pound, exclusive of tax. The utility of the article is indicated by its remarkable success as an article of merchandise—a success which is not attributable to the quality of the tobacco of which it is composed, or to the novelty of the style of manufacture, but to the inherent advantages which it possesses in the particulars which have been mentioned.

The novelty of the invention was clearly proved. It manifestly differs from the ordinary spun or rolled plug tobacco in this, that in such tobacco, the filler and binder are rolled together, while in the patented article the binder simply encircles the filler. “Twist,” or “braid” tobacco was made in the same manner as the patented article is made, by encircling the sweetened filler with two separate wrappings of unsweetened tobacco, but twist tobacco is simply braided and subjected to lateral pressure. Each plug is a flat braid, into the interstices of which air freely enters, and, having a comparatively thin and flat surface, the plug cannot be made compact by endwise pressure. The shape and the method of the formation of the coil, which render endwise pressure practicable, and which enable the coil to be compactly compressed without injury to the strands of the filler, constitute the particulars in which the patented article differs from braid tobacco.

The important question which arises in the case is as to the patentability of the invention. A rope of strands of sweetened filler, enclosed in a binder, which in turn is enveloped in a wrapper, ante-dated the patent, and is disclaimed. Plug tobacco had always been coiled and braided in various forms and had been subjected to pressure. The peculiarity of the invention is in the form and shape of the coil. Can any particular method of coiling, although both endwise and sidewise pressure are thereby made available for the purpose of excluding air, and although the method enables the consumer to use the whole coil in its desired state of moisture, be the subject of a valid patent? The argument of the defendants' counsel is, that the combination of filler, binder and wrapper is old and is disclaimed, which is true; that subjecting a coiled rope of such tobacco to pressure is old and is disclaimed, which is true; that coiling or twisting a moist rope of tobacco has always been practised, which is, also, true; that the particular form of the coil is a matter of fancy; and that the form of the coil cannot involve the exercise of the inventive faculty. This is the precise question which is at issue.

The article of plug tobacco has been long in use, and has been in constant demand. As it has been prepared for market, it has been liable to spoil in warm and damp weather, and to grow mouldy in any temperature. It is fair to presume that the ingenuity of tobacco manufacturers, and of tobacconists, has been exercised in an attempt to find a remedy for this liability to pecuniary loss. The evils were notorious, but no remedy was found until this invention was made. If the remedy consists in the shape of the coil, and if the particular twist of the coil requires no greater exercise of the inventive faculty than is involved in the shape of a bow into which a ribbon may be twisted, it is strange that an evil which had long existed had not previously been avoided. Two facts exist in this case. One is, that an important improvement has been attained. The second is, that the improvement is in a staple article, which has been manufactured in this country for a long series of years. Without the testimony of the patentee and the first manufacturer in regard to the number of experiments which were required before the invention was hit upon, and in regard to the difficulty which was experienced in perfecting the manufacture, it is manifest, from the length of time during which tobacco has been manufactured, from the constant demand for it, and from the well-known evils to be overcome, that the inventive faculty must have been brought into exercise, or else that mechanical skill would long since have avoided any 744 danger of fermentation or mould. The utility of the patented article has been evinced by its large sales, and by the unanimity with which rival tobacconists have commenced its manufacture. The inventor evidently gave to the public an article which it wanted, and which it had not previously known. Without giving to the general use of the invention, as a test of its patentability, any greater importance than the supreme court, in the case of Smith v. Good-year Dental Vulcanite Co., 93 U. S. 486, indicate should be given to this circumstance, I am of opinion, that the facts in the case fully establish the conclusions, (1) that, however simple the change in the method of manufacture apparently may have been, yet it was a change which required invention for its accomplishment; and (2) that the improvement resulting from the changed method of manufacture has been so great, that the article which is produced is, within the meaning of the patent acts, a new arid useful article of manufacture. Let there be a decree for an injunction and an account.

1 [Reported by Hon. Samuel Blatchford, Circuit Judge: reprinted in 3 Ban. & A. 69; and here republished by permission. Merw. Pat. Inv. 221, contains only a condensed report.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

Google.