Case No. 4,249.

EARTH CLOSET CO. v. FENNER et al.

[5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 15.]1

Circuit Court, D. Rhode Island.

Feb., 1871.

PROVISIONAL INJUNCTIONS—DISCRETION OF JUDGE—PATENT CASES.

1. In applications for provisional injunctions, the law makes the judge's discretion the rule, not unheedful that, in the qualities of mind which give character to an exercise of discretion, individuals differ scarcely less than in form and features. The judge is bound to decide a question of this kind as, in his judgment upon the particular case before him, the principles of equity and the practice of its courts warrant or dictate. For precedents in any recognized sense of the word, it is idle to search.

2. The patent having been reissued just before the bringing of the suit, no exclusive possession of the invention for any considerable time, accompanied by acquiescence by the public, nor any verdict, judgment, decree, or judicial order recognizing the validity of the claim having been shown, nor irreparable injury to the complainant having been averred, a provisional injunction was refused.

In equity. Motion for provisional injunction.

Suit brought [by the Earth Closet Company against William H. Fenner and others] upon letters patent [No. 91,474] for “improvement

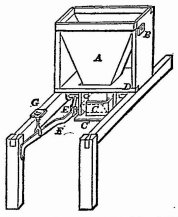

262in deodorizing apparatus for water-closets,” granted to Henry Moule and Henry J. Girdlestone [June 15, 1869]; assigned by them to Joseph W. Beach, and by him to the complainants, to whom they were reissued October 4, 1870, in two divisions, numbered 4,137 and 4,138 respectively, of which, however, No. 4,137, only, was involved in the present suit. The invention will be understood by a reference to the drawing, in connection with the claims.

The claims of the original patent were as follows: 1. The oscillating hopper A, the chucker C, upon the oscillating shaft E, the shelf C, pivoted lever F, and handle G, combined to operate within the case, substantially as described, for the purposes specified. 2. The oscillating hopper A, the chucker C, upon the oscillating shaft E, and the weighted levers, in combination with each other, and the seat, substantially as described, for the purpose specified.

The claims of the reissue No. 4,137 were as follows: 1. A vibratory or movable hopper, constructed and operating substantially as and for the purposes described. 2. A swinging distributor or chucker, arranged to operate substantially in the manner and for the purposes set forth. 3. The deflectorplate C, in combination with the chucker, operating as and for the purposes set forth.

Tillinghast & Carpenter, for complainants.

B. F. Thurston, for defendants.

KNOWLES, District Judge. Upon the pending motion in this cause, the parties have been fully heard at chambers. It is for a special, that is, a preliminary injunction, prayed for in the complainants' bill, charging an infringement of certain letters patent; and the state of facts, in view of which it is pressed, is substantially this:

On May 28,1860, letters patent were issued from the patent office of Great Britain to the Rev. Henry Moule, of Fordington, in the county of Dorset, clerk, and James Bannehr, of Exeter, agent, for the invention of “improvements in the nature and construction of closets and commodes for the reception and removal of excrementitious and other offensive matter, and in the manufacture of manure from them.” And it would seem that as early as October or November, 1867, there was in circulation, in London, a pamphlet of twenty-four pages, issued by a “Moule Patent Earth Closet Company,” giving the public full information in regard to earth closets and commodes, their utility, convenience, and economy, and showing, by numerous wood-cuts, the form and structure of the articles manufactured for sale by the company. On the title page of the pamphlet, among the names of the company's officers, are those of “Messrs. H. J. & J. W. Girdlestone, Consulting Engineers.”

On March 29, 1869, said Moule and Henry J. Girdlestone made application to the commissioner of patents of the United States, who, on June 15,1869, issued to them letters patent for a new and useful “improvement in deodorizing apparatus for water closets,” which letters patent the grantees, on August 9, 1869, transferred and assigned to one Joseph W. Beach, who, on September 2, 1869, assigned them to the complainants, the “Earth Closet Company,” a corporation under the laws of Connecticut.

On March 24, 1870, this corporation filed a bill of complaint in this court against the present defendants, charging an infringement of their said patent, to which the defendants answered, on May 17, 1870, in such terms that the complainants, after filing a general replication on July 4, withdrew their suit on October 17, 1870, paying defendants' costs, having already, on surrender of the patent of June, 1869, procured a reissue thereof on October 4, 1870 (No. 4,137), in which the invention is denominated an “improvement in deodorizing apparatus for closets,” the patentees' specifications and claims having been amended and enlarged in such manner as to sustain a charge of infringement against the defendants, as the users, without license, of two of the three improvements, specified and claimed as such under the reissue.

On October 15, 1870, the complainants filed a second bill, now pending, charging an infringement of their patent as thus reissued, and praying an account and an injunction, and also a preliminary injunction. On January 12, the complainants moved, in effect, that a preliminary injunction issue, and, on February 16, at chambers, this motion was heard.

The defendants, it is proper to add in this connection, in their affidavits, admit that, in the spring of 1869, they did manufacture earth closets of the form and kind depicted in the pamphlet above referred to, and that some of these thus manufactured had been sold since the reissue of the patent; denying, however, that since that reissue any of these articles had been made by them. They further say that no one of these closets made by them, saving some twenty or twenty-five, made prior to the date of the Moule & Girdlestone 263 patent (June 15, 1869), comprised “an oscillating hopper,” which, as they contend, was and is the only portion of the mechanism covered by that patent, as originally granted, and therefore the only portion covered de jure by the reissue of October, 1870.

Such being the facts, the complainants, presenting their reissue patent of October, 1870, as a valid patent from and after the date of the original (June 15, 1869), contend that, under existing laws and the rules of practice in the circuit courts of the United States, they are entitled to the injunction asked.

In opposition to this claim, the defendants submit several propositions, which they contend are tenable, in view of the facts admitted and in proof, and the law, as found in the Statutes at Large and in the recorded adjudications of the federal judiciary. Thus they say:

1. The said patent is void, inasmuch as the reissue is not for the same invention described in and protected by the original patent, which, say they, was simply for an “oscillating hopper,” and not for the “chucker” or “deflector” specified in the reissue, and which alone have been used by the defendants.

2. Said patent is void, inasmuch as the so-called improvements of Moule & Girdlestone are in truth but modifications of the apparatus patented in 1860, to Moule & Bannehr—covered by and included in that patent—and therefore not patentable in the United States in 1869. This, they argue, was the view of Moule and his associates, the owners and controllers of the English patent, wherefore no patent for these was ever taken out in England. And if this be not a tenable position, then, as an alternative one, they contend that these improvements, by whomsoever devised, were abandoned to public use—given to the world—by the publication of the pamphlet referred to, with its pictorial illustrations, shown by the evidence to have been in circulation in November, 1867, but believed to have been (as the defendants hope to show conclusively at a future day) in circulation, in substance, at a much earlier date.

3. Said patent is void, inasmuch as the reissue was granted to the complainants, without the oaths of the inventors that they were the inventors of the chucker and deflector, specified as patentable improvements in the reissue, though ignored as such (as defendants contend) in the original patent, granted upon their oaths. In a word, say the defendants, Moule & Girdlestone obtain a patent in June, 1869, making oath that they were the joint inventors of certain mechanism, so described that the defendants could, without infringing the patent, continue the business in which they had engaged prior to its issue; and, in October, 1870, that patent is surrendered by its owners, and a reissue granted to them, without the inventors' oath, under which (if the reissue be a valid patent) the defendants are bound, and may be compelled to abandon that business.

To these positions of the defendants, the complainants reply that their patent is prima facie proof of title on their part, and that this is not rebutted, or even appreciably weakened, by the proofs or arguments of the defendants; contending that upon some points the patent is in itself conclusive and unimpugnable proof, and upon others that the evidence of the defendants is pointless or unreliable. That the first and second points are legitimate grounds of defense to the bill, as well as to this motion, is not controverted; and that some of the questions presented are questions of evidence, of fact, and not of law, must be admitted in deference to the ruling of the supreme court in Bischoff v. Wethered, 9 Wall. [76 U. S.] 812. They are, moreover, questions upon which much testimony can and probably will be offered, and in regard to which it is to be anticipated even experts the most skilled and most truthful may differ. Hence I shrink from passing upon them, unaided by illumination from any other quarter than the affidavits of the two defendants and a zealous amateur adviser on the one side, and those of J. W. Beach (grantor of the complainants), C. W. Waring (agent of the complainants), and C. W. Beach, on the other. Said Justice Story, Barret v. Hall [Case No. 1,047]: “My humble knowledge does not permit me to venture on such difficult topics, and fortunately my duties as a judge do not require me to master them. I am content on this, as on other occasions, to hear from those who can give the proper instruction, and then to apply it to the solution of such questions of law as are fit to be entertained here.” Happily, however, any expression of opinion upon the incidental questions raised at the hearing is unneeded in this connection. Are the complainants upon the case made entitled to a preliminary injunction? is the question addressed to me; and my answer, whether an affirmative or a negative, must not be construed as indicating concurrence with either party in their views of the questions of law and fact raised and discussed. These may, at a subsequent stage of the cause, again become subjects of discussion, under circumstances more favorable to correctness of judgment than is a hurried hearing at chambers upon but the fragmentary evidence of parties in interest, in the unsatisfactory form of ex parte affidavits. Until then, in my judgment, can with great propriety be deferred any expression or even intimation of my views upon the merits of the complainants' case, or the tenableness of the defendants' positions in justification.

The motion is one of that class addressed, in technical parlance, to the discretion of the court. For precedents, in any recognized sense of that word, it is therefore idle to search. By one judge, an injunction may be 264 granted to-day, under a given state of facts, and by another, be refused to-morrow, upon identically the same state of facts, and yet neither functionary be chargeable with even error in judgment. The law makes the judge's discretion the rule, not unheedful that, in the qualities of mind which give character to an exercise of discretion, individuals differ scarcely less than in form and features. The judge is bound to decide a question of this kind as, in his judgment upon the particular case before him, the principles of equity and the practice of its courts warrant or dictate—and this, whether his decision be in accord or at variance with that of his brother officer, of whatever grade or whatever locality. The largest liberty imaginable is his, “with no rules to restrain—no after-reckonings to dread.” Neither upon appeal, nor by writ of error, nor even by petition for revisory action, can a judge's rulings or findings upon a motion for a preliminary injunction be subjected to correction or even criticism on the part of his superiors in official rank or in judicial acumen.

In the decisions of the supreme court, therefore, are found neither authoritative rules, nor even suggestive dicta, bearing upon the subject of preliminary injunctions. But this want, if such it be, we find supplied in the reports of decisions in the circuit courts of the several districts—decisions, in most instances, by justices of the supreme court, sitting as circuit judges—and from these, as would naturally be supposed, may be deduced some propositions entitled to grave consideration upon the part of the inexperienced judge called to pass upon a motion of this character. The inquirer learns by a glance at the circuit reports that motions of this sort are not infrequent in the several districts, and that many of the judges have, as occasion required, stated at length or curtly indicated their views of the judicial duty when the injunction power of their respective courts was invoked. For instance:

Justice Nelson, in Sickles v. Youngs [Case No. 12,838], says: “As this is a motion simply for a preliminary injunction, and not a case upon pleadings and proofs, for a final hearing, I shall not look further into the mass of papers before me than to ascertain whether or not a case has been made, which, upon established principles of equity, to prevent an irreparable injury, requires the court to interfere, pending the litigation, and restrain the defendants from the further use of the apparatus or machinery charged with infringement, until the right is finally determined. And upon these principles, it is well settled that, unless the right is clear upon the papers and proofs presented, and upon which the motion is founded, in favor of the plaintiffs, the injunction will be withheld, and the rights of the parties be left unaffected and unchanged, until the case is matured for the final hearing, and definitely disposed of.”

In this paragraph is clearly stated the principle or rule to be kept in mind by counsel, parties, and court. And if we turn to the reports of decisions in the first circuit, while we find nothing in conflict with this rule, we find in almost every volume recorded adjudications in harmony with it. Nor is this all. In many instances, the judges in this circuit (Story, Woodbury, Curtis, Clifford) have had occasion to state in what cases—that is, under what state of circumstances—a preliminary injunction would be granted or refused by them respectively in the exercise of a judicial discretion—as does Justice Woodbury in Orr v. Littlefield [Case No. 10,590], and Perry v. Parker [Id. 11,010]; and in Woodworth v. Rogers [Id. 18,018]. See, also, Foster v. Moore [Id. 4,978]; Sargeant v. Seagrave [Id. 12,365]; Forbush v. Bradford [Id. 4,930]; and Clum v. Brewer [Id. 2,909],—to name no others.

An examination of the decisions of the judges of this circuit, be it cursory or critical, it is believed, warrants the assertion that, by no one of the distinguished jurists above named, has it ever been held that a preliminary injunction should issue at the instance of a complaint, in a patent cause upon a state of facts not widely distinguishable from that shown in the case at bar, in several very important particulars. These it can subserve no desirable end here to specify. It seems sufficient to say that, taking as sound the dicta of Justice Nelson, as above quoted, I can find in the evidence and arguments of the complainants no sufficient ground for the pending motion, especially as a contrary conclusion would, in my view, be irreconcilable with the recorded adjudications of each and all of my predecessors in this circuit.

No exclusive possession of the invention for any considerable time, accompanied by acquiescence in their claim by the public, nor any verdict, judgment decree, or judicial order, recognizing that claim, do the complainants show or attempt to show, and (what is not less noteworthy in my view) it is not to be pretended that the injunction prayed for can, under the circumstances of this case, avert from the complainants any injury to which the epithet irreparable would not be glaringly inappropriate. The motion is overruled.

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

Google.