Case No. 4,239.

8FED.CAS.—16

EAMES v. COOK.

[2 Fish. Pat. Cas. 146.]1

Circuit Court, D. Massachusetts.

Dec., 1860.

PATENTS—ANTICIPATION—WHAT ARE MATERIAL DIFFERENCES—NEW RESULT—UTILITY—BOOT TREES.

1. In comparing the plaintiff's patent with any other machine, in order to determine whether the mechanism is the same, we must first see whether such other contains substantially the same devices; and, if it does, then

240whether the arrangement, or mode of applying them, is the same.

2. If either the devices or the mode of applying them, in any other machine, be substantially different, then the machine is not the same.

3. If the mode of operation be different, it is evidence that the mechanism is different. Or, if the result be different, then, reasoning from effects to causes, we may presume that some new instrumentality has been introduced.

4. But if, upon examining the mechanism, we find that it is substantially different in two machines, then they are not the same, although they may produce the same result.

[Cited in Seymour v. Osborne, Case No. 12,688.]

5. If an invention be new and useful, it can not be impeached because it does not accomplish all that a sanguine inventor has claimed for it.

6. If the mechanism employed by the patentee is materially different from that used by a prior inventor, and especially if it be of such increased utility as to have wholly superseded the prior machine, it is no answer to his claim for a patent to say that, after all, the boot was as well treed by the prior machine as it is by that of the patentee.

7. The practical utility of a new invention is frequently increased by new improvements or by the use of old instrumentalities or appliances which the inventor has not mentioned, either because it did not occur to him, or because he deemed it wholly unnecessary to point out what must be plain to every operator.

This was a motion for a new trial. A verdict had been rendered for the plaintiff [Charles T. Eames] in an action [against Aldrich S. Cook] on the case tried before Judge Sprague and a jury, to recover damages for the infringement of letters patent [No. 14,951] granted to plaintiff May 27, 1856, for an “improvement in boot trees.”

The patentee says: “I do not claim the employment of either two levers or cam, arranged so as to simultaneously operate against both the upper and lower part of the back portion of the leg of the tree; but I claim the arrangement or mode of applying a single cam F and inclined plane G, with respect to the foot and leg portion of the boot tree, whereby the said devices are made to first perform the function of setting the foot part C of the tree firmly into the foot of the boot; and next that of stretching the leg of the boot—the application of stretching mechanism directly to the upper part of the leg of the tree being rendered unnecessary.

The decision of the motion turned mainly upon the construction of the patent, and a comparison of the invention of Eames with a prior patent [No. 5,876] granted to Jarvis Howe, October 24, 1849.

F. A. Brookes, for plaintiff.

Causten Browne, for defendant.

SPRAGUE, District Judge. Upon a re-examination of the case, the view which I have taken of the patent and the application of the evidence which was given at the trial is as follows: The claim at the close of the specification of plaintiff's patent is in these words: “The above-described arrangement or mode of applying a single cam and inclined plane, with respect to the foot and leg portions of the boot tree, whereby the said devices are made to first perform the function of setting the foot parts of the tree firmly into the foot of the boot, and next that of stretching the leg of the boot—the application of stretching mechanism directly to the upper part of the leg of the tree being rendered unnecessary.” This claim may be divided into two parts: first, the mechanism, and second, the effect or result attained by the mechanism. The first, i.e., the mechanism, is the arrangement.

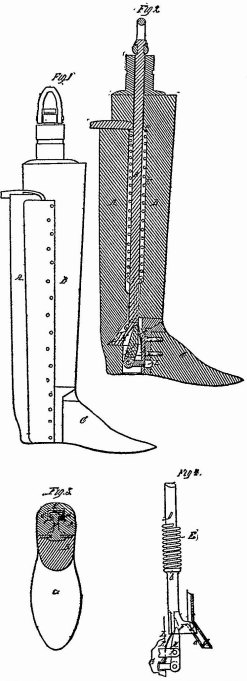

[Drawings of the Eames patent, No. 14,951, granted May 27, 1856, and published from the records of the United States patent office.] 241 or mode of applying a single cam and inclined plane. And this consists of two parts: First, the devices, and second, the mode of applying them. The mechanism, if it do not embrace all that is material in the plaintiff's patent, is at least an essential part of it; and when inquiring whether any other machine is similar, we must ascertain whether it embraces both its elements, viz: the devices, and the mode of applying them.

The first element, the devices, consists of a single cam and inclined plane, requiring no explanation. The second element viz: the arrangement or mode of applying these devices is to be ascertained only by looking at the previous specification. We there find that the leg part of the tree is divided into the back and front parts, called A and B, and that within the front part B is a rod, the lower end of which carries a cam, which works against an inclined plane, so that when the cam is moved upward by the rod, it will separate the back and front parts. The inclined plane is arranged within the back part A, so that it shall project both above and below the vertex of the angle of the instep of the foot, and the front side of the front part B. The came when drawn up by the rod, will work both above and below such vertex. The lower part of the inclined plane is placed about as high as the top of the heel. This is the arrangement of the devices. The cam is placed in the front part, and is moved up and down by means of a rod, to the end of which it is affixed, and so placed that it presses against and traverses the surface of the inclined plane. The inclined plane is fixed in the back part so that it projects both above and below the vertex of the angle made by the instep and leg, and its lower part is placed about as high as the top of the heel. The cam will thus work both above and below the vertex. In comparing the plaintiff's patent with any other machine in order to determine whether the mechanism is the same, we must first see whether such other contains substantially the same devices, and if it does, then whether the arrangement or mode of applying them is substantially the same, that is, does it contain a single cam and inclined plane, arranged, placed and applied in the manner above set forth? If either the devices or the mode of applying them, in any other machine, be substantially different from the plaintiff's, then it is not the same. In order to determine whether the mechanism of any other machine is the same as the plaintiff's, we may not only look at the mechanism itself, that is, the devices and the arrangement of them, but also at their mode of operation, and their effects or results. If the mode of operation be different, it is evidence that the mechanism is different. Or, if the result be different, then, reasoning from effects to causes, we may presume that some new instrumentality has been introduced. If, upon examining the mechanism, we find that it is substantially different in two machines, then they are not the same, although they may produce the same result. That would be the common case where the same end is attained by different processes or instrumentalities. But if a materially different result is reached, it is evidence of some new cause or means, although the mechanism may, apparently, be substantially the same. Hence, a greater degree of utility being achieved by one machine is evidence, and sometimes conclusive evidence, of novelty in the means or instrumentalities which are used.

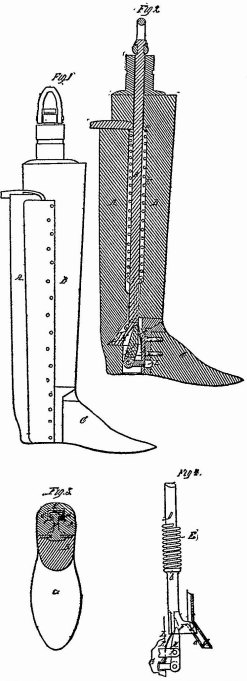

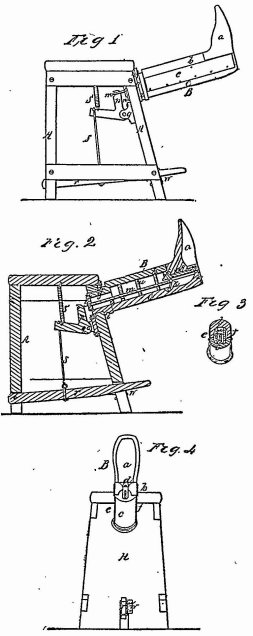

[Drawings of the Howe patent No. 5,876 granted October 24, 1848, and published from the records of the United States patent office.]

242In comparing the plaintiff's patent with the Howe machine we see that the devices are different, and the mode of applying them is different. The cam and inclined plane have been long known devices for certain purposes. But is not their application to a boot tree new, and is there not invention in passing from Howe's device—the toggle joint—and its mode of application, to the cam and inclined plane, and their mode of application?

First. By Howe's the power is applied at one point one inch and a half above the vertex of the above-mentioned angle. By the plaintiff's, the power is applied successively below and above that angle. Second. During the whole operation of the toggle joint, its power is constantly increasing, while that of the cam and inclined plane is always the same. Third. The toggle joint exerts its power at a fixed single joint only in the back and front part of the tree respectively. But the cam, moving upward on the inclined plane, exerts its power successively on all parts of the plane. Fourth. By this motion of the cam upward on the plane, their power is first applied more directly to the filling of the foot, and, afterward, more directly to the fitting of the leg. Whereas, by the toggle joint, the point of applying the power being always fixed, it does not operate any more directly to fill either the foot or leg at one time than at another. Fifth. The rod in the front part of the tree leg, to the end of which the cam is affixed, has a mechanism by which it is moved up and down, thus carrying with it the cam, and thus exerting its force on the inclined plane; while in Howe's there is no such rod or cam or mechanism to impart motion to any rod or cam. Sixth. The toggle joint fastens the front and back part of the tree together, which is not done by the cam and inclined plane. Seventh, By the mode in which the toggle joint is fixed to the front and back of the tree, it is rendered necessary that those parts should be made of metal; whereas, the mode in which the cam and inclined plane are affixed admits of their being made of wood.

We now come to the comparative utility of the two machines. It is admitted that the plaintiff's is of so much greater practical usefulness that it has superseded Howe's, and driven it out of use. As we have before stated, greater utility implies a difference in the machines. But it is insisted that in the present case that rule does not apply, because it is said that this greater utility arises from two causes: first, that the back and front not being fastened together in the plaintiff's machine, the backs may be changed with greater facility than in Howe's, and second, that the plaintiff's may be made of wood, whereas, Howe's require metal. But this explanation shows that the plaintiff's machine has capabilities important to its practical use, which Howe's has not, and these new capabilities are at least some evidence that the means, the machine, are different.

We have thus far not inquired into the ultimate effect of the one tree or the other; nor whether the plaintiff's machine will accomplish the work of treeing a boot any better than Howe's. It is insisted by the defendant that the plaintiff's has no such quality as he claims for it, of filling the foot first, and the leg afterward, any more than Howe's; and that in both, the foot and the leg are practically filled successively in the same manner and with equal facility and utility, at least when applied to the common run and various classes of boots, although it is admitted that as to a single class of boots the plaintiff's may have some advantage over Howe's in dispensing with the strap at the top. If this were so it would by no means follow that the two machines are the same. There are many instances of distinct patentable inventions producing the same result, that is, accomplishing the same work. For example, the Woodworth and Norcross planing machines not only plane a board equally well, but both do it by means of a rotary cutter applied to the surface. Yet the mechanism being different both properly received patents. A new machine which accomplishes the same end as a former, but by substantially different means, is patentable.

If, therefore, the mechanism used by Eames is materially different from that used by Howe, and especially if it be of such increased utility as to have wholly superseded Howe's, it is no answer to his claim for a patent to say, that after all the boot was as well treed by Howe's as it is by the plaintiff's. And it is unnecessary to enter into the question whether it was so or not. But it is insisted that the plaintiff's machine will not accomplish what he asserts it will. Now, if an invention be both new and useful, it can not be impeached because it does not accomplish all that a sanguine inventor has claimed for it. Still, let us see how far this objection is founded in fact. The useful result, which the plaintiff asserts that he has attained, is set forth in the close of his claim in the following words: “Whereby the said devices are made to first perform the function of setting the foot parts of the tree firmly into the foot of the boot and next that of stretching the leg of the boot, the application of stretching mechanism directly to the upper part of the leg of the tree being rendered unnecessary.” He here asserts that three things are achieved. In the first place, setting the foot parts of the tree firmly into the foot of the boot, and next the stretching the leg part of the boot, and rendering the application of the stretching mechanism to the upper part of the leg of the tree unnecessary. As to the third, the defendant does not deny that it is fully accomplished. But is the foot of the tree first set firmly into the foot of the boot and then the leg stretched? That the practical operation is, first, to set the 243 foot of the tree into the foot of the boot, and then to stretch the leg is clear, both from the testimony of operatives, and the laws of nature, and the only question that can arise of the perfect correctness of the plaintiff's statement is, whether the foot of the tree is set firmly into the foot of the boot before the leg is stretched? It is insisted by the defendant that, although the foot of the tree is first thrust into the foot of the boot, and next the leg stretched, that then the foot of the tree is again pressed into the foot, and more tightly than before. Now, if this were so, still the effect claimed by the plaintiff, that of first setting the foot of the tree firmly into the foot of the boot, is attained in a greater degree by the plaintiff's than it was by Howe's, because the force is applied at a lower point, and, therefore, more directly to the foot And there is little foundation for the criticism upon the word “firmly,” a word admitting of degrees. If the results, which the plaintiff asserts will be produced, are substantially attained, it is sufficient. The plaintiff's assertion as to the practical operation of his machine is substantially correct, even when compared with Howe's. This precludes the necessity of considering how far that assertion is material, and what would have been the consequence if the operation or result had been different from that asserted by the plaintiff. But, although it is not necessary to decide this question of construction, I would remark that it is not said in the closing part of the claim that the devices and arrangement must be such as to produce that result: far from it. The devices and their arrangement are distinctly described. And then it is said that these devices so arranged will produce two successive results. It would seem, therefore, that this closing assertion does not qualify or limit what precedes. In other words, that the invention claimed is the arrangement or mode of applying the devices, and that that arrangement or mode of applying is positively prescribed in a manner not to be varied whether the operation or effect attributed to them be attained or not.

The defendant insists that in the ordinary use of the plaintiff's machine for various classes and sizes of boots, it is necessary to use a strap at the top to limit the operation of the stretching force and prevent the leg from being split or ripped; and that the plaintiff has nowhere in his specification noticed this necessity. Very great stress is laid upon this objection. It is beyond controversy that the plaintiff's machine will operate usefully without such strap or check at the top, and, indeed, that there is no occasion for it when the boots to be treed are all of a certain size. Now, if a new machine is invented by which one class of boots is usefully treed, why is not such invention patentable? It may be true that the plaintiff's invention is rendered more useful by the use of a strap. But how frequent it is that the practical utility of a new invention is increased by new improvements, or by the use of old instrumentalities or appliances which the inventor has not mentioned either because it did not occur to him, or because he deemed it wholly unnecessary to point out what must be plain to every operator. But the defense, when scrutinized, really seems to consist in this, that the plaintiff only claims to have discovered a certain point or space where the power could be applied with greater advantage than it can be within any other space; and that he has made no such discovery: insisting that the point selected by Howe is as good as that pointed out by the plaintiff. This assumption that the plaintiff's claim is confined to the location of his devices, is unfounded. That is a part, but not the whole of his claim, which is expressly for the arrangement or mode of applying the devices “with respect to the foot and leg portions of the boot tree.” A part of that arrangement or mode is the fixing the inclined plane in the back part of the boot tree, and the cam at the end of a rod in the front part of the boot tree, which rod is moved up and down by mechanism, carrying the cam with it and against the inclined plane as before described. And the question is whether the cam and inclined plane, and the whole arrangement or mode of applying them, are substantially different from Howe's patent or machine? This question has already been considered. New trial denied.

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

Google.