Case No. 4,035.

The DOVE.

[1 Gall. 585.]1

Circuit Court, D. Massachusetts.

Oct. Term, 1813.

PRIZE—RECAPTURE—RESTITUTION.

The prize court has jurisdiction to decree restitution of a vessel recaptured from the enemy, and to award damages against the recaptors for embezzlement.2

[Cited in Williams v. Waterman, Case No. 17,745.]

STORY, Circuit Judge. This is a prize cause coming before the court under circumstances somewhat singular and embarrassing. The schooner Dove, laden with a cargo of Indian corn in bulk, consisting of 1051 bushels, and owned by the claimant sailed from New York for Boston, on or about the 29th of July, 1813. On her passage round Cape Cod, the schooner and cargo were, on or about the 12th of August, 1813, captured by the British sloop of war Curlew, the British frigate Nymph being in company. A prize master and four British seamen were put on board, and the master and crew removed out of the Dove. About fifteen bags of corn were taken from the cargo on board the Nymph; and soon afterwards the schooner parted from the Nymph. On Sunday, the 15th of August, the schooner was descried off the harbor of Harwich, and soon afterwards 980 ran aground on the bar. She was immediately taken possession of by four Americans, who went in a small boat from the shore, namely, Messrs. Joseph Nickerson, Edward Phillips, Theophilus Burgiss, and Israel Nickerson. They obtained a sloop, and put a part of the cargo on board of her; and the Dove, when thus lightened, floated off, and was then moored in the offing. The British prisoners were then landed, and secured by the recaptors. On Monday, the 16th of August, the schooner Dove, and the sloop with her, were brought into the harbor of Harwich. On the same day, Mr. Jeremiah Walker obtained a prize commission from the custom-house for a small whale boat with five men, boarded the Dove, as she was coming into the harbor, and by virtue of his commission, claimed to hold her, as prize. The actual recaptors either acted upon the presumption, that Mr. Walker had acquired a legal right to control the property, or they entered into an agreement to share in concert with him, for they acquiesced in his subsequent directions and orders. The actual recaptors seem to assert, that they acted under ignorance of their own rights; and Mr. Walker as explicitly considers them as entering into a joint engagement with him. It is not necessary to settle this point in a dispute between the present parties; though I strongly incline to the belief, that Mr. Walker attempted to use the ignorance of the actual recaptors for purposes of his own private interest, in a highly improper manner. Certain it is, that the whole merit of the recapture attaches to other persons. Mr. Walker did nothing to accomplish the original enterprise; and his subsequent interference was at a time, when the whole property was in complete security.

Immediately after taking possession, Mr. Walker proceeded, without any authority, to an unlivery of the cargo. Although on the capture by the Curlew, the ship's papers and documents were carried on board of the Nymph, the ownership of both vessel and cargo might be easily ascertained, as the port of Boston was declared on her stern to be the schooner's home. The pretence of Mr. Walker for this unlivery is intimated, in no equivocal terms, to have been the fear of plunder from the lawless character of the inhabitants of those shores. Such an imputation is so pregnant with disgrace and inhumanity, that I confess myself slow to believe in its perfect verity. If it were true, I should think that more exact and decisive allegations would have been made by the witnesses, and that the scene would have been faithfully acted over, under the strong temptations of the case before the court. If indeed there are to be found banditti on our coast, who, without hesitation, plunder the property, which misfortune throws into their hands, I most sincerely hope that the public arm will reach their deeds, and scourge this foul dishonor of our country. I know of but one degree of atrocity beyond it, that of luring by false lights the unhappy mariner to shipwreck, that the spoil may be more securely shared. I cannot however but think, that Mr. Walker's conduct was too precipitate, and that he might well have secured the property on board by a competent guard, or by officers of the customs, until the owners at Boston could have been consulted. If he had so done, it is highly probable, that the whole subject matter of the present controversy would have been avoided.

On the 23d of August, a libel was filed in the district court by Mr. Walker against the Dove and cargo, as prize to a “five handed boat,” duly commissioned on the 16th of August, and commanded by himself. Not the slightest intimation is given of the right or interest of the original recaptors; they are studiously suppressed from the libel. The deposition of the British prize-master was taken in preparatory, and in his examination, nothing is said as to any recapture, but that stated in the libel. It was only in the subsequent proceedings, that the real facts appeared, which were so disingenuously concealed by Mr. Walker. No apology has been attempted for this conduct of Mr. Walker, by which he sought to rob other persons of the reward of their meritorious services, and appropriate to himself an undeserved gain. The claimant, Mr. Ladd, having in the mean time heard of the recapture of his vessel, proceeded to Harwich, and there made an adjustment with the original recaptors, allowing them for salvage 100 bushels of corn, and the head money from the United States for the prisoners. On the 26th of August, at Harwich, Mr. Ladd met Mr. Walker, who had returned from Boston, whither he went to file the libel. An agreement was there entered into, by which Mr. Walker, and his lieutenant Jonathan Phillips, for themselves and the crew of the said five handed boat, agreed to deliver up to the said Ladd, or to “his order, on demand, the above vessel and cargo, in as good order as received, free from all expenses, charges, or demands, that may or shall be made against the same, from the time taken possession by us (i. e. Walker and his crew), until the same shall be delivered up;” and further, to discharge Mr. Ladd from all demands, proceedings and suits, in consequence of the detention of said vessel and cargo. Afterwards, on the same day, in consequence, it is said, of a great deficiency in the cargo discovered by Mr. Ladd, the parties entered into a second agreement, as follows: “It is mutually agreed by the subscribers, that on the full execution of the agreement entered into this day by Jeremiah Walker and Jonathan Phillips to William Ladd, and five hundred dollars in cash paid, that receipts in full of all demands shall be passed between us. Harwich, August 26, 1813. Signed, William Ladd, Jeremiah Walker.” In pursuance of this agreement,

981Mr. Ladd received his schooner and eight hundred forty-five and a half bushels of corn. The whole quantity landed, as Mr. Walker admits, was eight hundred and fifty-eight bushels. On the 28th of August, the parties again met to complete the execution of their agreement, at Mr. Walker's house. Mutual discharges were here drawn up in a very inartificial manner, and signed by the parties, purporting on each side to be made in consideration of fifty dollars received. At this meeting no persons were present, but Messrs. Ladd, Walker, and Phillips. No money was in fact paid to Mr. Ladd; and he alleges in his special affidavit, that Mr. Walker fraudulently and violently seized and took away the discharges signed by him, Mr. Ladd, without having complied With the terms (the payment of $500) on which alone they were to have any legal operation. Mr. Walker, in his affidavit, makes a general denial in very loose terms; and the parties respectively produce the counter receipts, which are filed in the cause. On the 2d day of September, the proctor for Mr. Ladd gave notice to the proctor of Mr. Walker in Boston, that the supposed settlement was fraudulent, and that, at the return day of the libel, a claim would be interposed against Mr. Walker, for damages. Mr. Walker was at this time in Boston, and ordered his libel to be discontinued. On the 10th of September, the return day of the libel, the same not having been entered for trial, Mr. Ladd filed a petition and affidavit stating the special facts, on which a monition was afterwards issued against Mr. Walker, to proceed to adjudication. To this monition Mr. Walker has appeared, and filed his special exceptive bar and affidavit, relying on the agreements and discharges of the 28th of August Upon the hearing in the district court the cause was dismissed; and an appeal being interposed, it has now been heard upon the allegations of the parties and the new evidence submitted to this court.

It has been argued, that this court ought not to take jurisdiction of the cause, because the question, as between these parties, was put at rest by the agreements before stated; and if these agreements have not been executed in good faith, a common law remedy is open to the aggrieved party. The jurisdiction of this court over the present as a prize cause, is incontestible; and having possession of the principal cause, it will exert itself over all the incidents and collateral questions. Whether it will, in any given case, interfere, and compel the party to proceed to adjudication, depends upon sound discretion. Certainly it would not choose to interfere after a great lapse of time, and gross laches in the claimant. But when the claim is recent, and the tort manifest I see no reason to decline the jurisdiction, merely because a detached fragment of the cause may have assumed a shape fitted for the interference of mere common law courts. Nor should I think it expedient to turn the party round to such tribunals, however high my respect is for them, when it is very possible, that in the progress of the inquiry, a question of prize might intermix in the cause; a question, of which such courts have not jurisdiction. The embarrassment would be extreme, and unless a peremptory bar created by the party should exist, it would involve the claimant in a conflict of jurisdictions, at once expensive and tedious. The prize jurisdiction too seems the proper tribunal for questions like that before the court. It can measure out its rewards and damages from an investigation of the whole merits. It can consider the extent and the apportionment of salvage; and try the facts by compelling the answers of the parties on their solemn oaths. It is no disrespect to the common law courts, to state that the very exclusion of prize questions from their cognizance must materially narrow the view, which they are at liberty to take, of any detached incident And if the adjustment in this case was obtained by fraud, it may admit of some doubt whether the common law courts can administer an adequate remedy. At all events, it would be a reflection upon the prize court, to suffer a fraud to oust the aggrieved Party of his legitimate remedy. If indeed the claimant had, by any solemn act, renounced his claim to damages, or had executed the supposed discharges in good faith; it would be too much to say, that this court ought to interfere, merely because the party has since become dissatisfied. But supposing these discharges were never executed, but fraudulently or surreptitiously obtained, there can be no legal ground to make such fraud an exceptive bar to further proceedings.

Now, whatever doubts might very properly be entertained, as to the fact of such fraudulent conduct, upon the evidence in the district court, I feel no hesitation in saying, that the new evidence here appears to me decisive, that the discharges were not voluntarily or fairly delivered. The deposition of Mr. Phillips (introduced in behalf of Mr. Walker) is so equivocal, disingenuous, and evasive that it authorizes the most violent presumptions against his coadjutor. His very silence, as to the occasion of the quarrel between the parties; his studied ignorance of all the special circumstances attending the delivery of the papers; and his misstatements of material facts relative to himself, throw a suspicion over his testimony, that necessarily involves his principal. Combining this deposition with the relaxed and general denial of Mr. Walker, and the testimony of Mr. Prince, it seems difficult to resist the conclusion, that the discharges of the 28th of August came into the hands of Mr. Walker, mala fide. It is probable, that Mr. Walker thought, upon reflection, that in agreeing to give $500 to the claimant for the deficiency 982 discovered in the corn, he had acted with imprudence, and taken the hardship of an unequal bargain. But the mode he adopted to relieve himself, was as unjustifiable as it was dishonorable. The agreements of the 26th of August were but executory, and if he were overreached, as he now pretends, he was not without relief in this or in any other court. And even now, late as it is, as the claimant asks our interposition in his, behalf, if the sum stipulated be in equity and good conscience, in sound and substantial justice, too much, the party shall not be without relief.

And this leads me to the argument in defence, that, upon the whole facts disclosed, the claimant has no merits, and is entitled to no damages, because he has received his vessel and all the cargo, which came to the possession of Mr. Walker. I do not however, consider this defence on the merits to be fully supported. Ordinarily, after a capture by an enemy, a presumption of subtraction or a portion of the cargo might arise. But it is a presumption liable to be rebutted. And in the present case, there is strong evidence taken by Mr. Walker himself, that shows no more than 14 or 15 bags of corn were taken out by the enemy. The residue came into the possession of the recaptors, and there is not the slightest evidence to show, that a single bushel was embezzled by them. On the contrary, the proof is pretty direct, that the whole of the recaptured cargo came into the custody of Mr. Walker.

Undoubtedly, Mr. Walker is not responsible for more than came to his actual possession; nor for more than fair and reasonable diligence in the custody thereof. The deficiency is very considerable, even after a liberal allowance for that portion taken by the enemy. It is incredible, that Mr. Walker should agree to give $500 on account of the deficiency, unless he was sensible, that it was properly imputable to him. He had taken counsel on the subject of his rights, and had filed an allegation in the alternative, as a case of prize or of salvage. Under such circumstances, he agreed to discontinue the legal proceedings, to pay his own costs and expenses, and to pay the claimant $500. I am aware, that this sum was considered in the district court, as nomine poenae a mere penalty to secure the performance of the principal agreement, as to the restoration of the property. I cannot yield to this construction of the words of the instrument, and it seems irreconcilable also with the actual intentions of the parties. It is also material, that no such construction is asserted by Mr. Walker in his affidavit; and Mr. Ladd asserts positively, that it was a sum to be paid him for damages. This assertion of Mr. Ladd is no where contradicted or denied: and this silence certainly authorizes me to say, that the sum was not a penalty. Under all these circumstances, I must conclude that Mr. Walker had withheld from the claimant the whole quantity of corn which was deficient Nor do I think, that the terms of the discharges of the 28th of August invalidate this conclusion. They are very inartificially drawn, and acknowledge a receipt of $30 on each side in full of all demands. Either this sum is merely nominal, or the parties had materially varied in their respective claims. At all events, as the transactions of the 28th of August never acquired a legal validity, they offer no sufficient presumption to weaken the inferences from the preceding conduct of the parties. Had Mr. Walker behaved correctly, although he might not have been entitled strictly to salvage, yet the court would have been indulgent in allowing him a recompense for his services, in the preservation of the property. Embezzlement of property saved, is a forfeiture of the right of salvage. I would not apply so harsh an imputation to Mr. Walker; but he cannot expect after so much impropriety and disingenuousness, that this court should listen to any claim for a recompense in the nature of salvage. He must, therefore, be confined to the allowance of such expenses only, as were incurred in the actual landing of the cargo; and I shall allow a reasonable sum for these expenses, to be deducted from the damages, which he may be ordered to pay to the claimant.

I shall order a decree, that Mr. Ladd recover against Mr. Walker the value of the deficiency of the cargo, deducting the allowance aforesaid, and his costs in these proceedings. The actual damage sustained by Mr. Ladd, and no more, can be recovered. Probable profits can form no item in the account; and, as to other allowances claimed, it cannot be necessary for me to state my reasons for rejecting them. The value of the corn must be estimated at the market price at Harwich, at the time of landing.

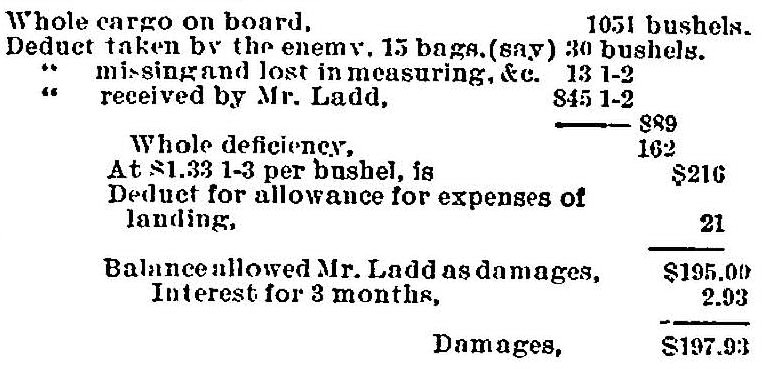

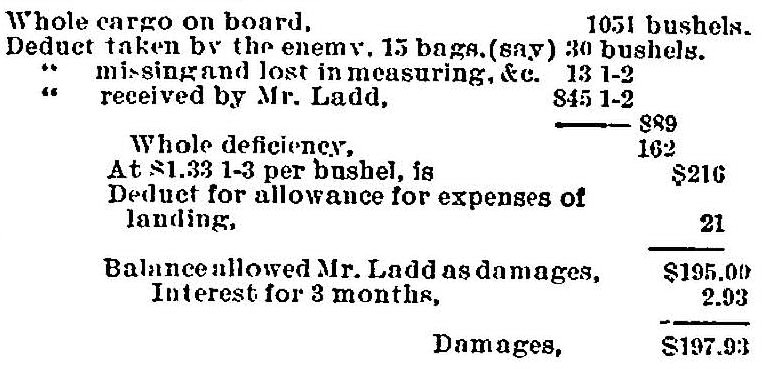

On these principles and facts, the following account is adjusted:—

1 [Reported by John Gallison, Esq.]

2 See The Mary [Case No. 9,184]; The Joseph [Case No. 7,538: The Concordia, 2 C. Rob. Adm. 102; Mason v. The Blaireau, 2 Cranch [6 U. S.] 240; S. P. applied in case of salvors. See The Bello Corrunes, 6 Wheat. [19 U. S.] 152; The Boston & Cargo [Case No. 1,673].

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

Google.