Case No. 4,014.

7FED.CAS.—60

DORSEY HARVESTER REVOLVING-RAKE CO. v. MARSH et al.

[6 Fish. Pat. Cas. 387;19 Phila. 395; 30 Leg. Int. 169; 5 Leg. Gaz. 139.]

Circuit Court, E. D. Pennsylvania.

April 7, 1873.

CORPORATIONS—PROOF OF CORPORATE EXISTENCE—PATENT FROM STATE—CORPORATE POWERS, HOW ASCERTAINED—PATENTS FOR INVENTIONS—ISSUANCE BY ACTING COMMISSIONER—REISSUES—INFRINGEMENT—INJUNCTION.

1. It is well settled that patents granted by a state or the general government are to be taken as prima facie evidence that they were regularly granted, and that they import conformity to the few requisitions of the laws authorizing their allowance.

2. The acceptance of the charter is essential in the process of constituting a body politic, and must be proved when the existence of the corporation is put in issue.

3. But it is well settled that acceptance will be presumed from facts which are consistent only with such hypothesis, without proof of any express declaration to that effect.

4. When a general law is in existence authorizing the creation of a corporation by letters patent, to be issued by a public officer, upon the performance of certain preliminary conditions, and letters patent are duly issued, reciting the performance of the conditions and investing the corporation with the franchises of a body politic, and these letters patent are produced by the corporation to establish its existence, it will be presumed that they were granted at the instance of the corporation and accepted by it.

5. The corporate faculties of a corporation are not to be ascertained by reference exclusively to the statutes authorizing its creation. Notice will be taken of any supplementary or general statute pertinent to the inquiry.

6. The purpose of a corporation may be inferred from its corporate name.

7. A corporation has power to purchase an invention which would tend to facilitate the purposes of its incorporation, as indicated by its

940corporate name, even in the absence of any law expressly conferring it.

8. A provisional officer, who is invested by law with the functions of the commissioner of patents, is properly described as commissioner so far as the efficacy of his official acts is concerned.

9. The actual incumbent of a public office is presumed to be in the lawful possession of it, and no affirmative proof of his title is required to support his official acts.

10. The contingency upon which the examiner-in-chief is authorized to assume the duties of commissioner is primarily to be taken to exist from his actual discharge of these duties.

11. The burden of showing the non-existence of the prescribed contingency is upon the party who denies the validity of the ostensible officer's acts.

12. When a patent is extended in apparent conformity to the act of congress, the decision of the officer granting the extension has the attributes of a final judgment. It is not subject to appeal or revision.

13. In a suit by a patentee against an in fringer, it can not be shown that the commissioner who granted the patent exceeded or irregularly exercised his authority, except by matter apparent on the face of the patent. The patent is conclusively valid until it is successfully impeached in a direct proceeding properly instituted for that purpose.

[Cited in brief in National Hay-Rake Co. v. Harbert, Case No. 10,044. Cited in Brown v. Deere. 6 Fed. 490: Fassett v. Ewart Manuf'g Co., 58 Fed. 364.]

14. A reissued patent can not be allowed for an invention different from the one of which the original patent is the basis. But any feature of an invention which is actually a part of it, that was only suggested or indicated in the specification or drawings, may be distinctly described in a reissued specification, and be protected by a reissued patent.

[Cited in Gould v. Ballard, Case No. 5,635.]

15. The claims of a reissue may be restricted or enlarged to cover the real invention.

[Cited in Gould v. Ballard, Case No. 5,635.]

16. It is no objection to a renewed patent that part of the original patent is omitted.

[Cited in Gould v. Ballard. Case No. 5,635.]

17. Absolute precision is not required in a specification. It is sufficient if a mechanic skilled in the art to which the invention pertains, not simply an ordinary mechanic, can from the specification and drawings, construct and use the invention described.

18. Dorsey's invention construed to be “a rake, with its arms attached by a pivot to a shaft, with which it revolves, and so that it will rise and fall as the arm passes along the surface of a cam, by which this latter movement is regulated and controlled.”

19. The reissued patent granted Owen Dorsey, June 9, 1868, No. 2,982, for improvement in harvester-rakes, and extended March 4, 1870, held valid, and infringed by the machines made in accordance with the patent granted James S. Marsh, February 28, 1871, for improvement in harvester-rakes.

20. When the complainant is not a manufacturer of the patented article, and the defendant is an extensive manufacturer, with large capital invested, the court will withhold the issuing of the injunction, upon the filing by defendant of an ample bond, with good security, for the payment of such sum as may be ultimately decreed to complainant for profits and damages.

[Distinguished in Consolidated Roller-Mill Co. v. Coombs, 39 Fed. 804.]

In equity, Final hearing upon pleadings and proofs. Suit brought [against James S. Marsh and others] upon reissued letters patent for “improvement in harvester-rakes,” granted Owen Dorsey, June 9, 1868, No. 2,982, as a reissue of the patent originally granted him March 4, 1856 [No. 14,350]. The patent was extended for seven years, from March 4, 1870.

The claims of the patent were: “(1) A continuously revolving-rake, attached by a pivotal connection to the shaft on which it revolves, so as to allow it to describe the proper path, to gather or discharge the grain, and to clear the frame. (2) The combination of a platform, a vibrating cutter, and a continuously revolving, gathering, and discharging rake, so arranged as to enter the uncut grain in front of the cutter, and to discharge the cut grain in the arc of a circle. (3) A continuously revolving, gathering, and discharging rake, which enters the uncut grain in front of the cutters, and discharges the cut grain in the arc of a circle, in combination with one or more immediate revolving gathering heads or beaters. (4) The combination of a continuously revolving, gathering, and discharging rake, which discharges the grain in the arc of a circle, and the cam-way or guide for regulating the course of the rake. (5) The combination of a continuously revolving-rake, which discharges the grain in the arc of a circle, with a platform, having a fender conformed substantially to the path described by the outer end of the revolving-rake in passing over the same, substantially as described. (6) The combination of a continuously revolving, gathering, and discharging rake, which discharges the grain in the arc of a circle with a vibrating cutter. (7) The combination of a continuously revolving, gathering, and discharging rake, a cam-way or guide, and

friction rollers, attached to the arms of said revolving-rake.”

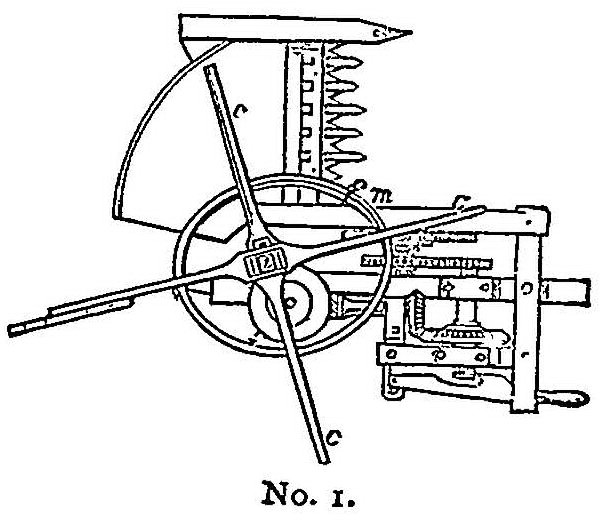

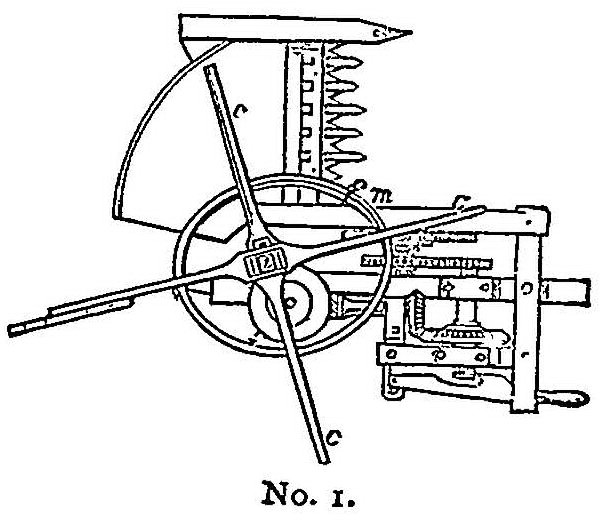

In the drawings, Fig. 1 represents a top view of Dorsey's harvester-rake, as shown in the original patent, and Fig. 2 a side view i is the pivoted shaft, to which the diametrically opposite arms c, c are attached; f, m, f is the guide-way or cam for regulating the elevation of the rake-head.

The operation is described in the original patent as follows: “As the rake-head passes over the platform A, its movement is horizontal, the arm C passing over the rail from m to h; but, on reaching the edge of the platform, the rake-head is suddenly raised by the arm passing up the incline, m, of the guide-rail, while the rake and opposite end of the arm drops at a corresponding incline; and, by continuing its movement, the rake reaches over the heads of the grain, and, gradually descending by the guide-rail, draws the wheat toward the cutters.”

The claim of the original was: “The combination, with the rake-arms c, c, to which the rakes are firmly attached, of the vertical revolving-shaft i and cam-way or guide f, f, m, m, from which the rake-arms receive an undulating motion in a vertical plane, revolving about said shaft i, substantially in the manner and for the purposes set forth.”

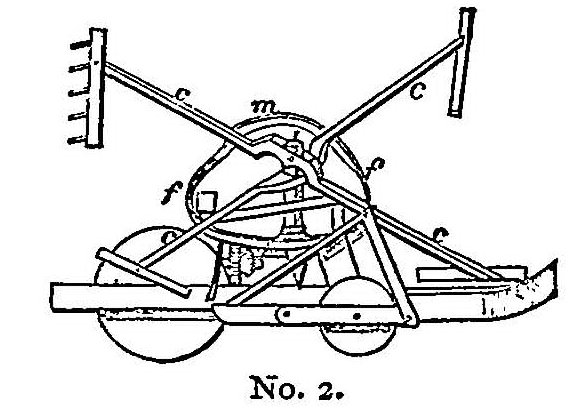

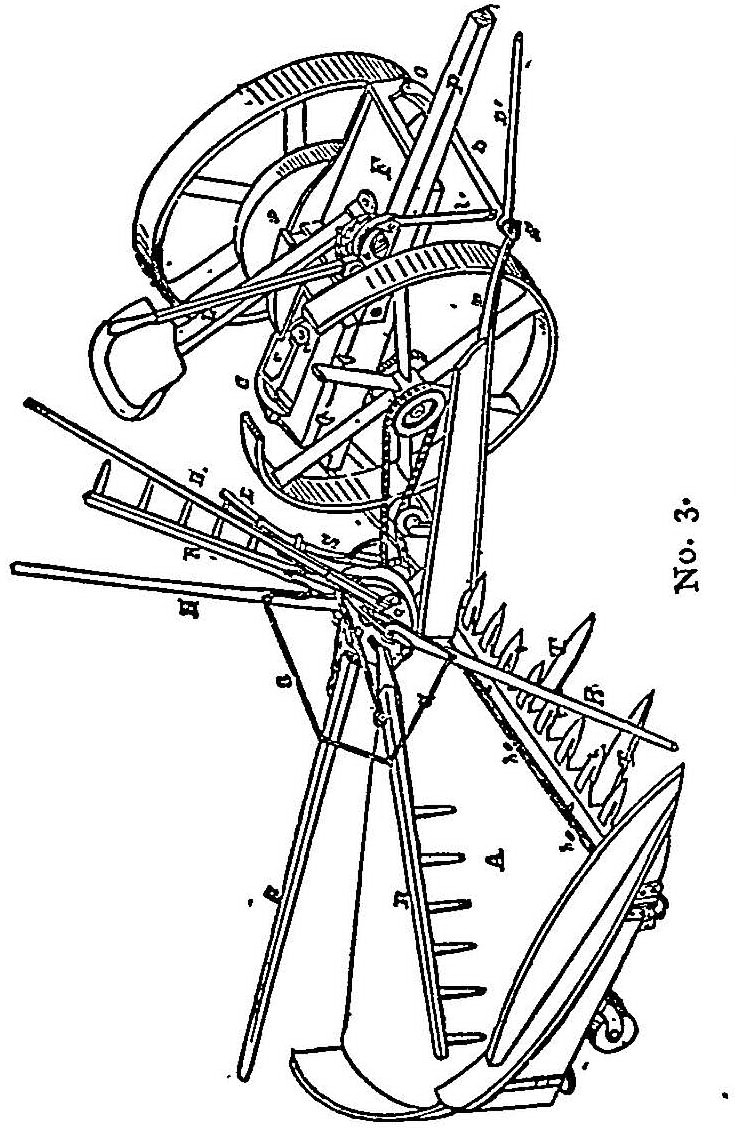

The machine constructed by Marsh was substantially the same as patented by him February 28,1871.

Fig. 3 shows this rake as illustrated in the patent, and will be readily understood when examined in connection with the opinion of the court.

George Harding, for complainant.

David Wright, for defendant.

MCKENNAN, Circuit Judge. The bill in this case is founded upon an extended patent to Owen Dorsey, for an improvement in harvester-rakes, dated March 4, 1870. Every material allegation of the bill is denied in the answer; and the validity of the patent and the sufficiency of the complainant's proofs have been contested in an argument of unusual minuteness of elaboration. It has failed to convince me that the complainant is not entitled to a decree, and the reasons for the conclusion reached by me can perhaps be more briefly and lucidly stated by an examination of the points of that argument, in the order in which they were presented.

The suit is brought by the complainant as a corporation, and its existence as such is denied in the answer. It is proved by the exhibition of letters patent, issued under the great seal of the state of Pennsylvania, signed by the governor, and countersigned by the secretary of state. That the governor had authority to cause these letters to be issued, is indisputable, and if they do not warrant a presumption that they were rightfully issued, and therefore that what the law prescribes as necessary to be done to that end had been done, it is difficult to perceive what significance they have. To the acts of public officers within the general scope of their power, some degree of faith and credit is due, and it is no stretch of presumption to consider that they have faithfully performed a duty imposed upon them by law, with a proper observance of all its preliminary conditions. Therefore, it has been held, and is settled law, that patents granted by a state or the general government are to be taken as prima facie evidence that they were regularly granted, and that they import conformity to the prerequisitions of the laws authorizing their allowance. Trenton R. Co. v. Stinson, 14 Pet [39 U. S.] 458; Rubber Co. v. Goodyear, 9 Wall. [76 U. S.] 797.

Nor has the second branch of the objection, that the acceptance of the charter is not shown, any better foothold. This fact is undoubtedly essential in the process of constituting a body politic, and it must therefore be proved where the existence of the corporation is put in issue. But it is well settled that it will be presumed from facts, which are consistent only with such hypothesis, without proof of any express declaration to that effect. Thus, where a law is enacted applicable to a designated corporation, the mere passage of the law will not sufficiently prove its adoption by the corporation. But where it appears that the law was enacted upon the application of the corporation, its acceptance is a necessary inference from that fact. And so where a general law is in existence, authorizing the creation of a corporation by letters patent to be issued by a public officer upon the preliminary performance 942 of certain things by the persons to be incorporated, and letters patent are duly issued, reciting the performance of the required conditions, and investing the corporation with the franchises of a body politic, and these letters are obtained and produced by the corporation for the very purpose of establishing its existence, can any doubt remain that they were granted at the instance of the alleged corporation, and were accepted by it? The possession by a grantee of a deed for his benefit, is everywhere sufficient prima facie evidence of its acceptance by him. Why, therefore, will not the same facts authorize a like presumption as to a corporation? The proofs here leave no doubt that the complainant was duly constituted a corporation according to law.

It is further denied that the complainant has any right to acquire and hold the patent in question. The corporate faculties of the complainant are not to be ascertained by reference exclusively to the statutes authorizing its creation. Notice will also be taken of any supplementary or general statute pertinent to the inquiry. Now, the Pennsylvania statute referred to in the complainant's letters patent authorizes the creation of a corporation upon the fulfillment of certain prescribed conditions, and they are recited to show that these conditions have been complied with, and, as a consequence, it is declared that the applicants are constituted a body politic, “with all the rights, powers, and privileges,” conferred upon it by “all the laws of the commonwealth.” The creation of the corporation was thus complete, but its powers are not to be sought in these acts alone. The supplementary act of February 27, 1867, extended the scope of the original act, so as to embrace companies thereafter formed for the purchase and sale of patents granted by the authority of the United States, and of rights and licenses under said patents. The right to acquire and hold patents is here clearly given to corporations organized under the original act, thus amplified. If the patent in controversy is related to the purpose of the complainant's organization, the right to take and hold it is expressly conferred upon it. It is not requisite that this purpose should be proved by direct evidence, but it may be inferred from the name of the corporation alone. So it was held in Blanchard's Gunstock Turning Factory v. Warner [Case No. 1,521], where it was inferred that the corporation, plaintiff, “had power enough to purchase an invention which would tend to facilitate the purposes of its incorporation, as indicated by its corporate name,” in the absence of proof of any law expressly conferring it. But in this case the law expressly authorizes the purchase and tenure by the complainants of a patent, which is cognate to the purpose of its incorporation. That it is founded upon the Dorsey patent, I think, is manifestly indicated. It adopts the name of Dorsey's invention, set forth in his patent, as part of its own; but to individuate the patent more distinctly, it superadds Dorsey's name, so that its corporate style, “The Dorsey Revolving. Harvester Rake Company,” denotes exclusively Dorsey's invention. I think, therefore, the inference is both legitimate and obvious, that the purpose of the complainant was to operate in reference to the Dorsey invention, and that it has the right to acquire and hold his patent.

The third point is purely verbal. The bill alleges that the Dorsey patent was duly extended by the commissioner of patents, and the proof is that the extension was granted by S. H. Hodges, acting commissioner, and it is therefore urged that the bill must be dismissed, because the proof does not support the averment. The gist of the averment is, that the patent was extended by an officer having authority to grant it, and if the proof substantially supports it, there is no discordance between them. A provisional officer who is invested by law with the functions of the commissioner of patents, is properly described as commissioner, so far as the efficacy of his official acts is concerned, and for this purpose only is it necessary to describe him at all. The validity of his act, not the verbal accuracy of his title, is the essential subject of inquiry.

The fourth and fifth points may be considered together. They affirm that the acting commissioner did not acquire jurisdiction to consider Dorsey's application for an extension, and that his patent was not extended until after the expiration of the original term.

The actual incumbent of a public office is presumed to be in the lawful possession of it, and no affirmative proof of his title is required to support his official acts. This is a familiar maxim. Accordingly, it was held in Winans v. York & M. L. R. Co., 17 How. [58 U. S.] 41, that “the court will take notice, judicially, of the persons who, from time to time, preside over the patent office, whether permanently or transiently, and the production of their commission is not necessary to support their official acts.” So, therefore, the contingency upon which the examiner-in-chief is authorized to assume the duties of commissioner, is primarily to be taken to exist from his actual discharge of these duties. That this presumption is conclusive, in a contest between third parties, is, I think, a logical result of the principle affirmed and applied in Rubber Co. v. Goodyear, 9 Wall. [76 U. S.] 796. But, at any rate, the burden of showing the non-existence of the prescribed contingency is upon the party who denies the validity of the ostensible officer's acts. That burden the respondents here have not sustained. They have shown only that the commissioner was at the patent office part of the day on which the extension was granted, not later than 11½ o'clock a. m.; while it appears that the commissioner, in writing, informed the chief examiner of his intended absence at the time of the decision of Dorsey's 943 application, and that the case was actually decided by the chief examiner. There was an actual abdication by the commissioner of his official functions, and an exercise of them by the chief examiner; and, as this was done with a distinct reference to the provisions of the act of congress, the inference that they were strictly observed is legitimate and fair.

The granting of an extended patent is a judicial act. Authority to that end is conferred upon the commissioner of patents by act of congress. The manner in which it is to be exercised, and the time within which it may be exercised, are prescribed by the act. The extension must be granted before the term of the original patent expires; but when it is granted, in apparent conformity to the act of congress, the decision of the officer has the attributes of a final judgment. It is not subject to appeal or revision. This is the clear import of numerous decisions of the supreme court. In Seymour v. Osborne, 11 Wall. [78 U. S.] 516, the court says: “When the commissioner accepts a surrender of an original patent, and grants a new patent, his decision in the premises, in a suit for infringement, is final and conclusive, and is not re-examinable in such suit in the circuit court, unless it is apparent upon the face of the patent that he has exceeded his authority; that there is such a repugnancy between the old and new patents that it must be held, as matter of legal construction, that the new patent is not for the same invention as that embraced and secured in the original patent.” And this doctrine is asserted with equal distinctness, in reference to the granting of an extended patent, in Rubber Co. v. Goodyear; Wall. [76 U. S.] 798. It is there said: “The law made it the duty of the commissioner to examine and decide. He had full jurisdiction. The function he performed was judicial in its character. No provision is made for appeal or review. His decision must be held conclusive until the patent is impeached in a proceeding had directly for that purpose, according to the rules which define the remedy, as shown by the precedents and authorities upon the subject.”

It is plain, from these authorities, that in a suit by a patentee against an infringer, it can not be shown that the commissioner who granted the patent exceeded or irregularly exercised his authority, except by matter apparent on the face of the patent, and that it is conclusively valid until it is successfully impeached in a direct proceeding, properly instituted for that purpose. We have, then, a case where a patent has been extended, with every apparent legal sanction, which it is sought to invalidate by parol evidence contradictory of its purport, and claimed to show that it was granted at a time and place contrary to law. This is a forbidden inquiry in this case, and it is therefore unnecessary to notice the evidence presented in relation to it.

The invention of Dorsey belongs to the widely useful class of mechanical devices designed to facilitate the harvesting of grain. His special object was to produce a device which would automatically separate the standing grain in suitable gavels, press it against the vibrating knives of a reaping machine, and, sweeping it in the arc of a circle, deposit it in the rear of the machine, out of the way of the team when it passed round again. By no pre-existing invention was this double effect produced. The function of discharging the cut grain had been performed by a rake sweeping over the platform of the machine, and of separating and gathering the standing grain to the cutters by a revolving reel. These were the more recent and approved automatic devices for these purposes, preceding the invention of Dorsey. But in all the literature of the art, which has been so exhaustively exhibited, no instance is shown in which the gathering office was performed by a rake.

To effectuate his object, Dorsey constructed a continuously revolving-rake, with arms attached by a pivot to a shaft or head, around which they revolve, and so as to allow of their being elevated or depressed by an inclined cam-way, on which they rest. Guided by the cam, the rake is caused to fall in front of the cutter-bar into the standing grain, thereby separating it for each gavel, pressing it against the cutting-knives, and sweeping it over the platform in the arc of a circle, depositing it behind the horses and out of their track on their next round.

The novelty of the operation consists in the performance of the functions of gathering the grain to the cutters and discharging it from the platform by the same instrumentality, and in the mechanical means employed to guide and cause it to rise and fall to perform these functions together. And in these features the complainants invention is distinguishable from the various devices exhibited by the respondents. I do not propose to consider them in detail, but content myself with saying that in none of them is a rake employed to separate and gather to the cutters the standing grain, nor is there in any of them a similar pivotal attachment of a rake-arm, by which it is capable of rising and falling in its revolving movement; and in all of them, except in Seymour's and Palmer and Williams', the cut grain is discharged directly behind the cutter. I can have no doubt, therefore, of the novelty of the invention.

It is urged that the patent in controversy is void, because the reissue is not for the same invention described in the original. That a reissued patent can not be allowed for an invention different from the one of which the original patent is the basis, is undoubtedly true. But it is equally true that any feature of the invention, which is actually a part of it that was only suggested or indicated in the specification or drawings, may be distinctly described in an amended 944 specification and protected by a reissued patent, and that accordingly the claims of the patent may be restricted or enlarged to cover the real invention.

It is a just rule that patents are to be construed liberally, so as to sustain the right of the inventor. Mere verbal discrepancies, therefore, are entitled to but little consideration, especially where, in view of the mechanism devised, the functions it was designed to perform, and its mode of operation, there is substantial accordance between the original and reissued patents. Nor is it any objection to a renewed patent that part of the original invention is omitted. This an inventor may do, because the public may use it, and there is nothing in the policy or terms of the patent act which forbids it. Carver v. Braintree Manuf'g Co. [Case No. 2,485].

I do not think, however, that it requires any great liberality of construction to harmonize the original and reissued patents. The main ground of the objection is that in the reissue the invention is described as a continuously revolving, gathering, and discharging rake, which descends into the standing grain in front of the cutter, so as to gather the grain for each gavel, and that the gathering function thus defined is not suggested or indicated in the original patent. In the latter it is said “the rake-head is brought by a sweeping descent upon the front edge of the platform, and in so doing draws the uncut grain toward the cutters.” And, again, describing the operation of the rake, “by continuing its movement, the rake reaches over the heads of the grain, and gradually descending by the guide-rail, draws the wheat toward the cutters. By this means, I dispense entirely with the reel used on harvesters for drawing the grain to the cutters.” Now, the reference here to the gathering function of the rake is distinct. It is expressly stated to be a substitute for the reel, the sole function of which is to gather the grain to the cutters; and it operates so as to reach over the heads of the grain, and, descending gradually, draws or gathers the grain to the cutters. Every step in the process is not as fully described as in the amended specification, but it is obviously implied that the rake, reaching over the heads of the grain, was intended to descend below them into the grain, as it could thus only perform its appointed duty of drawing it to the cutter; and, in so operating, it must necessarily effect a separation of the grain between the rake-head and the cutter-bar from that standing in the rest of the field. The description, therefore, plainly points to a rake adapted to gather the grain to the cutter, as well as to discharge it from the platform, and, in so performing its intended office, necessarily passes down into the grain in front of the cutters, and divides it so as to form the succeeding gavel in the standing grain.

Again, it is objected that the original and amended specifications are vitally irreconcilable in this: that in the former is described a rake attached to the end of a diametrical arm; “each pair of arms, formed of metal or wood, with an opening at their half length of a longitudinal form, so as to allow them to pass over the end of a vertical turning-shaft;” and that this description is omitted in the latter. Diametrical arms are undoubtedly one form of embodiment of the patentee's conception, but they are not the only one to which the principle of his invention is susceptible of application, nor is it so declared. His patent covered equivalent, although formally different, mechanical devices, which operated in the same way and to the same end with diametrical arms. Hence it was legitimate to modify the specification so as to secure protection broadly to the real invention of the patentee against any form of infringement. This is well and accurately illustrated by Acting Commissioner Hodges, in his opinion, where he says, in reference to the distinctive merit of the invention: “It lies in attaching the rake-arm by a pivot to a shaft, around which it revolves, and may be made at the same time to rise and fall upon the pivot. By this construction the rake may be guided in the direction desired. These are the essential features of the invention, and equally so whether the arms are diametrical or merely radial. After trying the latter, Dorsey adopted the former, because he found he could use the limb opposite the rake as a means for guiding it. But the combination of the revolving movement of the arms and their swinging movement upon their pivots, which alone gave him the power to direct the path of the rake at will, was common to both, and constitutes the merit of the contrivance.”

Nor does the objection apply with any greater effect to the claims of the reissue. It has been already shown that the original and amended specifications describe a continuously revolving-rake, with a pivotal connection to the shaft on which it revolves, which performs the functions of gathering and discharging the grain, so arranged as to enter the uncut grain in front of the cutters, and discharge the cut grain in the arc of a circle, and so as to separate the grain which is to form the next gavel in the standing grain. It follows, therefore, that the claims of the reissue which embrace the device and combination of devices by which these functions are performed, are in entire harmony with the specification.

Another objection to the validity of the patent is that the patentee has not so described his raking device and its arrangement as to enable an ordinary mechanic to make, construct, and use the same. Absolute precision as to details is not required in the specification. It is only intended as a guide; but it is not the sole instructor. Nor is it addressed merely to ordinary mechanics; but the test of its sufficiency is whether 945 a person skilled in the art to which the invention appertains can construct and use it. The special skill of the mechanic, derived from familiarity with the art, may he applied in aid of the instruction given by the specification, and this skill may be exerted to modify any direction in the specification as to the matters of mere adjustment or adaptation of the invention to its intended use, else the authority to employ it at all is of but little value. “It will, perhaps, rarely happen, even where the utmost vigilance and care are observed, that the machine or structure will be so accurately described as that the description can be literally and strictly followed in every particular. The skilled mechanic will see that in some particulars there is some vagueness, and some discretion is required, but that fact will not invalidate the patent.” Seymour v. Osborne [Case No. 12,688]. But it is a complete answer to the objection that the thing which, it is argued, can not be done, has actually been done. In 1858, Adam Reese acquired a license to use the Dorsey invention, and, in substantial accordance with the specification and drawings, he made and applied it to over fifteen hundred machines, which worked successfully. Against such a practical demonstration, argumentative speculation, reinforced though it may be by the untested opinions of experts, will be of little avail.

In Union Sugar Refinery v. Matthiessen [Case No. 14,399], Mr. Justice Clifford said to the jury: “You will regard the well-known substantial equivalent of a thing as being the same as the thing itself; so that if two machines have the same mode of operation, do the same work, in substantially the same way, and accomplish substantially the same results, they are the same; and so also, if the parts of two machines, having the same mode of operation, do the same work, in substantially the same way, and accomplish substantially the same results, these parts are the same, although they may differ in name, form, or shape.”

The invention of Dorsey consists of a rake, with its arms attached by a pivot to a shaft, with which it revolves, and so that it will rise and fall as the arm passes along the surface of a cam, by which this latter movement is regulated and controlled. It operates with a continuous revolution, descending with the inclination of the cam in front of the cutter-bar, thence sweeping backward in the arc of a circle to the rear of the platform, where it is elevated by the cam to clear the frame of the machine, and, passing again to the front repeats the movement. Its functions are to descend into the standing grain in front of the cutter, thus separating the grain which is to form the next gavel, to draw or gather it to the cutter, and when cut, onto the platform, and then to sweep it across the platform in the arc of a circle, and to discharge it onto the ground out of the way of the return of the machine in cutting its next swarth. These are the characteristic features of the invention.

Now, the alleged infringing devices embodied in the defendants' machines “have substantially the same mode of operation, do the same work, in substantially the same way, and accomplish substantially the same results” as those claimed by the complainants. In the defendants' machine is to be observed a rake-head, with an arm attached to a crown-wheel or head, with which it revolves, and to which it is pivotally connected, so that it will rise and fall under the guidance and control of a cam-way. It revolves continuously, descending into the grain in front of the cutter, separating the gavel, gathering it to the cutter, and, traversing the platform in the arc of a circle, discharges the grain in the rear by a side delivery, out of the way of the return of the machine, and then rising clears the machine and renews the operation. It is obvious, then, that the functions and mode of operation of both devices are substantially the same. In their construction the differences are formal rather than substantial. Instead of a vertical post, the shaft and head of which are of one piece, and revolve together, to which the rake-arm is attached, as in the Dorsey invention, the defendants employ a vertical iron shaft, which passes through the center of a metal head, to which the rake-arm is attached, and which revolves around this shaft, instead of with it; but the mode of operation and the results accomplished by both devices are the same. In Dorsey's drawings and model a diametrical rake-arm is shown; in the defendants' machine the rake-arm is radial, but both are pivoted at the same point to the central revolving head, and are alike guided and governed by the cam in their rising and falling movement. The defendants use a cam, formed in a segment of a circle, while Dorsey's cam is a complete circle; but I think the part of the latter, at its lowest inclination, where the defendants' cam is open, exerts no essential agency in guiding the rake in its traverse on the platform, and that therefore the difference in form between the two is immaterial.

Upon the whole case, I am of the opinion the complainant is entitled to a decree; but it ought to be so framed as not to subject the defendants to any avoidable loss or injury. The complainant is not a manufacturer of reaping-machines, so far as appears, and will be adequately protected by the payment of a just compensation for the use of the Dorsey invention. The defendants have an extensive establishment, and a large capital invested in it for the manufacture of machines, and seem to have conducted their business under the impression that it was no invasion of the rights of others. A sudden stoppage of it would be disastrous to them, and would not benefit the complainant.

A decree will therefore be entered for an injunction and an account; but no injunction 946 will issue until the further order of the court, if the defendants, within thirty days from the date of this decree, file a bond, in such form and amount, and with such security, as the court or judge thereof may approve, to secure to the complainant the profits and damages which they may ultimately be decreed to pay.

[NOTE. For another case involving this patent, see Dorsey Revolving Harvester Rake Co. v. Bradley Manuf'g Co., Case No. 4,015.]

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

Google.