Case No. 3,929.

7FED.CAS.—48

DIXON v. COLUMBUS, ETC., R. CO.

[4 Biss. 137.]1

Circuit Court, D. Indiana.

Jan., 1868.

FREIGUT BILL—CONSTRUCTION—ONUS PROBANDI—LOSS BEYOND CARRIER'S LINE.

1. A freight bill is a contract; and its effect cannot be varied by parol evidence.

2. A freight bill ending “Acc't Henry Dixon,” and signed “W. T. Noell & Co., Agents,” may be construed as made to Henry Dixon, he being In fact the consignee.

3. The words “I. & C. Central R. R.” cannot, without an allegation of misnomer, or offer to prove the identity, be taken to mean the Columbus and Indianapolis Railway Co., in a contract not purporting to be made by such company.

4. Where a freight bill is signed “W. T. Noell & Co., Agents,” not appearing on its face to he the contract of a railroad company, parol evidence is not admissible to show that it is the contract of the company.

5. In the charge of a breach of a common law duty—as the duty of a common carrier—denied by the defendant, the burden of proving the breach is with the party alleging it, whether it is alleged as a mal-feasance or a non-feasance; and he cannot recover without proving it.

6. Where a railroad company received goods for transportation to a point beyond their own terminus, and the plaintiff alleges that they undertook to carry the whole distance by rail, the burden is upon him to prove such undertaking.[Cited in Robinson v. Memphis & C. R. Co., 9 Fed. 139.]

7. In such case the burden is not upon the carrier to account for the loss, if he has delivered at his own terminus to a proper person.

[This is an action at law by Henry Dixon against the Columbus and Indianapolis Railroad Company.]

McDonald & Roach, for plaintiff.

J. S. Ketcham, for defendant

MCDONALD, District Judge. This is an action of assumpsit the declaration contains two counts. The first count charges that the defendant is a common carrier from Indianapolis, Indiana, to Columbus, Ohio, in the direction of New York, its road forming one of several connecting lines from the city of Evansville to the city of New York; and that on the 12th of October, 1865, the defendant entered into a written contract with the plaintiff, and thereby promised, in consideration of the payment of freight, to transport twenty-five hogsheads of tobacco, worth four thousand dollars, from Evansville to New York by railroad. The count then avers that the plaintiff “shipped” said tobacco on the Evansville and Crawfordsville Railroad, which carried it to Terre Haute and delivered it to the Terre Haute and Richmond Railroad Company, which transported it to Indianapolis, and there delivered it to the defendant, to be by the defendant carried over its road in the direction of the city of New York; and that the defendant failed to deliver said tobacco at the eastern terminus of its road to any connecting line to be transported by rail to the last-named city; but on the contrary, forwarded it by rail to Baltimore, and thence by water toward New York, whereby the tobacco was lost at sea.

The second count is substantially like the first except that alleging no contract in writing, it avers that the defendant engaged to carry the tobacco from Indianapolis to New York “by railroad and not otherwise,” and “permitted it to deviate from the said route by railroad,” and to be transported part of said distance by water in boats; whereby it was lost at sea. The defendant pleads the general issue.

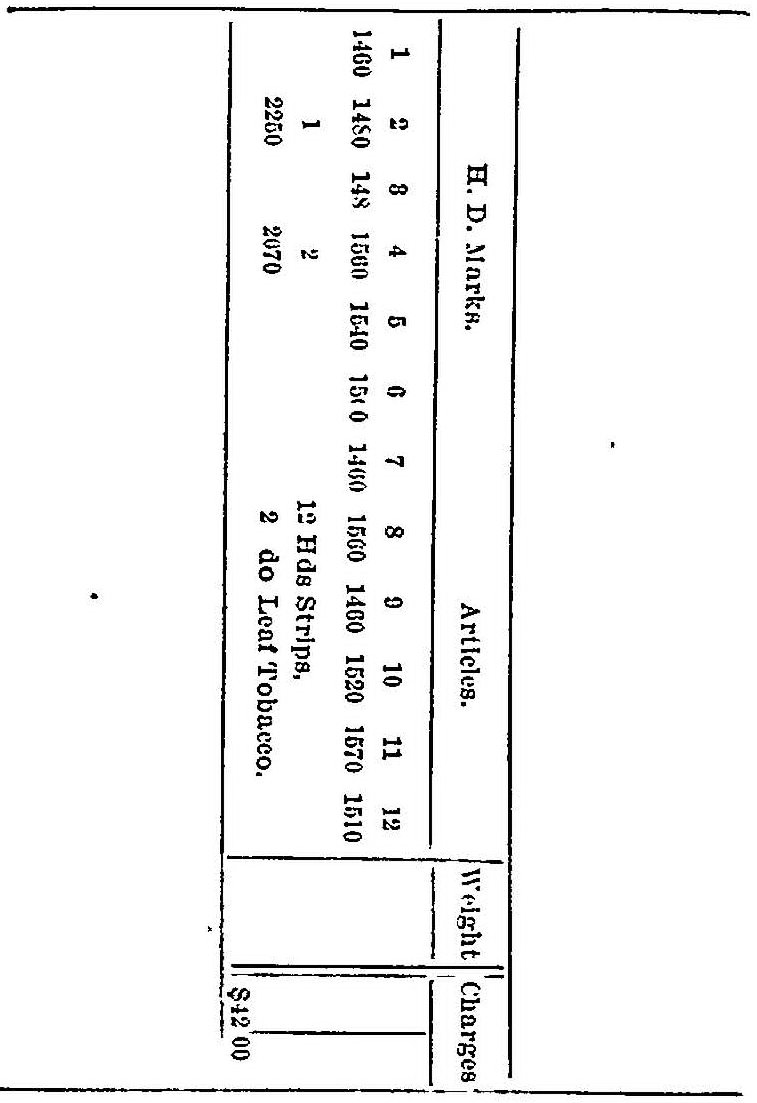

By agreement this cause is submitted for trial to the court without a jury. On the trial, the plaintiff proved the delivery of seven hogsheads of tobacco on the 12th of October, 1865, to the Evansville and Crawfordsville Railroad Company, and its carriage, by that company, to Terre Haute, thence by the Terre Haute and Richmond Railroad Company to Indianapolis, thence by the defendants railroad to Columbus,

752Ohio, thence by a direct railroad line to Benwood, thence by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to Baltimore, thence by a steamer for New York. The plaintiff also proved that the tobacco never reached New York, and that it would have been worth three thousand and fifty-six dollars and ten cents at New York, had it reached that place in due course of transportation.

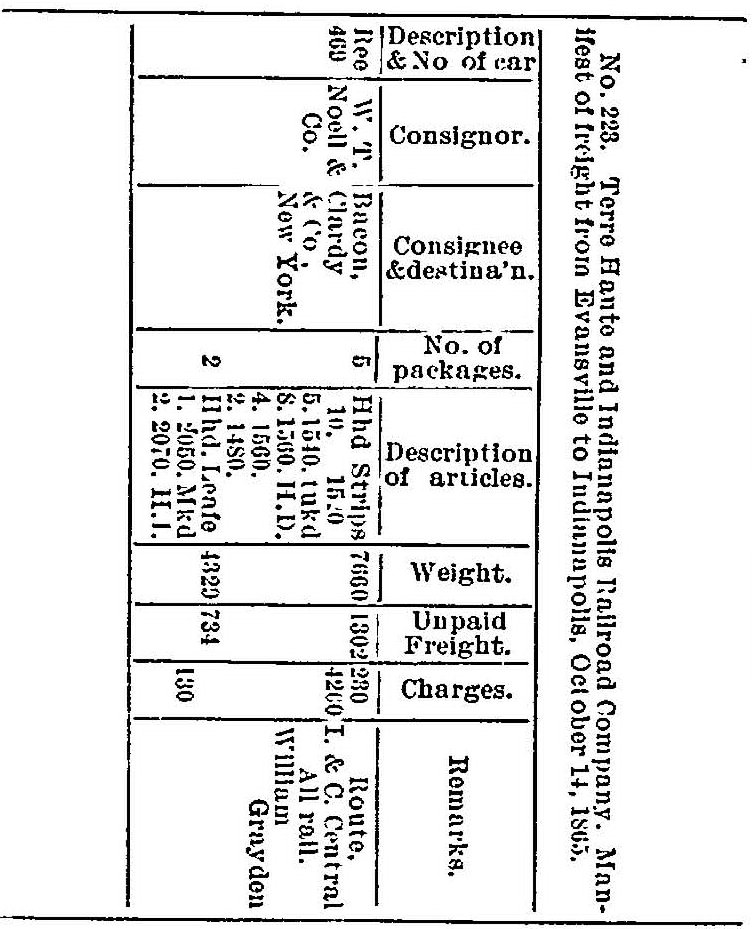

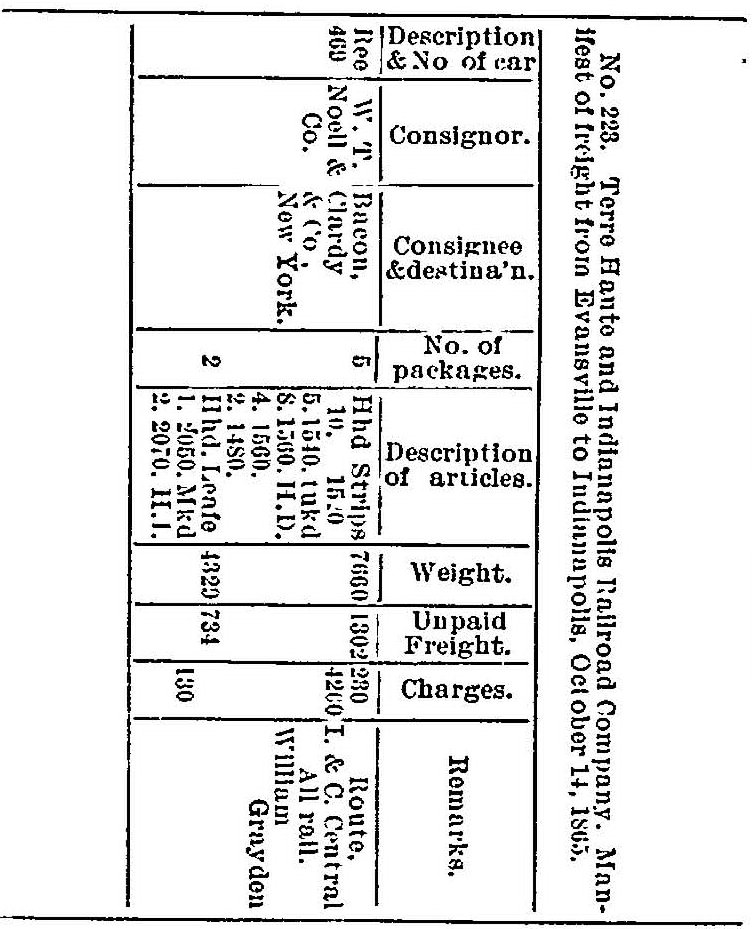

The plaintiff also produced in evidence a freight-book of the Terre Haute and Richmond Railroad Company, in which is contained the following manifest:

The plaintiff further proved that William Grayden, whose signature appears to the above manifest, was, at the time when it was made, the defendant's freight agent at Indianapolis. The manifest was read in evidence without objection from the defendant. Preparatory to the production in evidence of the writing hereinafter copied, the plaintiff further proved that W. T. Noell & Company, mentioned therein, and residing at Evansville, were in October, 1865, the agents of the defendant to solicit and procure freight to be passed over the railroad of the defendant; that said W. T. Noell & Co. executed the said writing, and that about that time they executed many other writings, all which the defendant had recognized and ratified as being done by the said W. T. Noell & Co. as the defendant's agents. This latter evidence was given under the objection of the defendant.

The plaintiff thereupon offered in evidence said writing, which is as follows:”

W. T. Noell & Co., Forwarding and Commission Merchants, and agents for the Great Eastern Express Line, via Evansville and Indianapolis.

“Through Bill of Lading.

“Evansville, Indiana, October 12th, 1865.

“Received from W. T. Noell & Co., in apparent good order, the articles described below, contents and value unknown, which are to be transported to Terre Haute by the Evansville and Crawfordsville Railroad Company, and thence via Terre Haute and Richmond Railroad and connecting roads, I. and C. Central R. R., all rail, to Messrs. Bacon, Clardy & Co., at the customary place of delivery in New York, he or they paying freight at the rate—cents, if of first class; if of 2d class,—cents; if of 3d class, SO cents; if of 4th class, per 100 pounds,—cents; per bbl.,—and charges as below.”

And it is agreed and is a part of the consideration of this contract, that the several carriers and parties in whose charge said goods may be, between this and the place of delivery, are not to be held responsible for any loss or damage arising from the danger of the seas, or railroad, canal, river, or lake transportation, or from providential causes; for delay of perishable articles, or for loss or damage to packages, the bulk of which renders it necessary to forward them in open cars; or from fire from any cause while in transit or at stations; nor for any accident or delay from any unavoidable cause. And it is further agreed that in case of any loss, detriment, or damage done to or sustained by any of the property herein receipted for, whereby any legal liability or responsibility shall or may be incurred, that company shall alone be held answerable therefor in whose actual custody the same may be at the time of the happening of such loss, damage or detriment.

It is understood that the shipper, in accepting this bill of lading, agrees to all its terms and conditions.

“Sell leaf in New York, and forward strips to Messrs. Robert Kerr & Son, Liverpool. Acc't Henry Dixon, Esq., Henderson, Ky.

“W. T. Noell & Co., Agents.”

The defendant objected to this paper as evidence: First, because it is only a receipt, and not a contract; secondly, because on its face it does not purport to be a contract, of the defendant. These objections were held over till the final decision on the evidence; and I now proceed to decide them.

1. It is argued that this writing is not a contract, but a mere receipt. Certainly, in its general features, it seems to be a bill of lading; and a bill of lading is always a contract—one which, according to the authorities, may be assigned very much like a note or bill of exchange. Conard v. Atlantic Ins. Co., 1 Pet [26 U. S.] 386. Singularly enough, however, at first sight this would seem to be a bill of lading executed by W. T. Noell & Co. to W. T. Noell & Co., for it is signed by that company, and it begins with these words: “Received from W. T. Noell & Co.,”; and if it is a receipt made by them to them it is a nullity. But, on a closer inspection, we find that it ends thus: “Acc't of Henry Dixon, Esq., Henderson, Ky.” In view of this language, and of the maxim that written contracts should, if possible, be so construed “ut res magis valeat quam pereat” I am inclined to hold the instrument as being made to the plaintiff, Henry Dixon. If I am right in construing this to be a bill of lading made to the plaintiff by W. T. Noell & Co., there can be no doubt that it is a contract For it contains an express agreement as to the liabilities of the carriers. Indeed, it seems very plain that it is a receipt and a contract both.

2. It is insisted that this bill of lading does not on its face, even prima facie, purport to be the contract of the defendant. It appears to me that this objection is well taken. The name of the defendant does “not appear in it. It is true that in stating the route which the tobacco was to take, it has this phrase: “I. & C. Central R. R.” But this is not the name of the defendant or the defendant's road. If the phrase had been the “C. & I. Central R. R.,” perhaps the court ought' to construe it to mean the defendant's road. But as there is no allegation of a misnomer in the declaration, and no offer to prove that the “I. & C. Central R. R.” means the Columbus & Indianapolis Railway, I think the court cannot officially take notice of such meaning.

On its face, then, this bill of lading does not appear to be the contract of the defendant, and the question is, can the plaintiff be permitted by parol evidence, to prove that it is the defendant's contract? I think he cannot I think that on its face, the bill of lading is the receipt and contract of TV. T. Noell & Co., and not of the defendant. The general rule, that parol evidence is inadmissible to add to or vary the terms of a written contract is too well settled to require any citation of authorities, and I see no reason for not applying this general rule to the contract in question. It has been applied in several cases. Higgins v. X. S. Mail Steamship Co. [Case No. 6,469]; The Reeside [Id. 11,637]; Goodrich v. Norris Lid. 5,545].

The circumstance that, to the signature of TV. T. Noell & Co., to this bill of lading, is added the term” “Agents,” amounts to nothing: If, on examining the whole bill, we do not construe it so as to make Noell & Co. “agents for the Great Eastern Express Line,” whatever that may be, I think we must regard the term “Agents” attached to their signature as mere descriptio personarum. McClure v. Bennett 1 Blackf. 189; Hobbs v. Cowden, 20 Ind. 310; Pentz v. Stanton, 10 Wend. 271. The plaintiff insists that the case of Mechanics' Barik v. Bank of Columbia, 5 Wheat. [18 U. S.] 326, is in point to show that parol evidence to aid this bill of lading is admissible. In that case the check sued on was as follows: “Mechanics' Bank of Alexandria, June 25,1817. Cashier of the Bank of Columbia: Pay to the order of P. H. Minor, Esq., ten thousand dollars. W. Patton, Jr.”

The question was, whether the Mechanics' Bank was liable on this check, and it was decided in the affirmative. And the court said that “the appearance of the corporate name of the institution on the face of the paper at once leads to the belief that it is a corporate and not an individual transaction.” “The evidence, therefore, on the face of the bill predominates in favor of its being a bank transaction.” This ruling goes as far as I would be willing to follow. But, whether right or wrong, the case is evidently different from the one at bar. The ground of the decision was that because the name of the Mechanics' Bank was at the head of the draft, it was prima facie the act of the bank. But in the present case, the defendant's name is not at the head of the bill of lading, or any where in it or on it No one looking at it could suppose that it is a contract by the Columbus & Indianapolis Central Railway Company.

On the whole, then, I rule out the bill of lading as evidence against the defendant. On this ruling, the plaintiff cannot recover on his first count. For as it is on a written agreement, and as he shows no such agreement in evidence, there is a failure of proof to sustain it.

It remains to be inquired whether the evidence sustains the second count of the declaration. This count, as we have already seen, is on a parol contract It charges that the defendant received the tobacco in question at Indianapolis, and, on sufficient consideration, promised to carry it by railroad to New York, and, in violation of that promise, permitted it to deviate from said route by railroad, and 754 to be transported part of said distance by water, in boats. Are all these allegations substantially proved?

I think it is fair to conclude from the evidence, that the defendant did receive from the plaintiff, at Indianapolis, the tobacco in question, and did promise to carry it to Columbus, Ohio, and there to deliver it to some other railroad carrier for transportation on a usual and safe route all the way by rail to New York. I conclude also from the evidence, that, if the defendant did so carry the tobacco to Columbus, and did so deliver it there to some other railroad company whose track formed a linK in a usual and fair line of transportation by rail to New York, directing it to be so transported, the defendant is not liable in this action.

There is not the slightest evidence that the defendant promised to carry the tobacco to New York by rail or any other conveyance. But, as the defendant must be presumed, from the manifest shown in evidence, to have known that the plaintiff intended that his tobacco should be carried all the way by rail to New York, and as the defendant with this knowledge undertook to carry the goods to Columbus, an implied obligation followed to deliver the tobacco there on some other road forming a link in a proper and usual line of transportation by rail to its destination in New York, and notify the party to whom the same was so delivered of the plaintiff's direction to have it earned all the way by rail. Did the defendant do this? And if there is not evidence on any point included in this duty, what is the legal presumption? The answers to these two questions must decide the plaintiff's right to recover on his second count.

1. Did the defendant carry the goods to Columbus, and there deliver them to some other company whose road formed a link in a proper and usual line of transportation by rail from Columbus to New York, and notify the company to which such delivery was made of the plaintiff's direction to carry all the way by rail? It is clearly proved that the defendant carried the goods to Columbus. It is also clear that, at that city, the defendant delivered the goods to a company whose railroad led directly to Benwood, the western terminus of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; and that they were carried on the two last-named roads from Columbus to Baltimore. At Baltimore, it appears that the tobacco was put on a steamer to be carried by sea to New York. The evidence adduced by the defendant also proves that from Columbus to New York there are several usual and proper through freight railroad lines; and that one of these is by the way of Benwood and Baltimore, though it is not the nearest and most direct line. It is certain that the tobacco might have gone all the way by rail on this line to New York; that it was a usual and proper line for freight transportation to that city from Columbus, Ohio; and that, forsending the tobacco on that line, the defendant, therefore, is not chargeable with any breach of duty. But did the defendant in delivering the tobacco to be carried on this line properly direct that it should be carried all the way by rail? On this point there is no evidence.

2. The only remaining question, then, is, what is the legal presumption? The defendant having performed all the other duties of a carrier, ought we to presume, in the absence of all proof, that on the delivery of the tobacco at Columbus to be carried by the route past Benwood and Baltimore to New York, the defendant properly directed that such carriage should be all the way by rail? In other words, as to this point, on whom does the burden of proof devolve? If the plaintiff had proved the allegation in his second count, that the defendant, for valuable consideration, promised to carry the tobacco all the way by rail to New York, this question would be unimportant. But as there is not sufficient proof of that promise, the question, I think, is the turning point in the case.

It is, indeed, a general rale that he who affirms a proposition must prove it. To this rule, however, there are many exceptions, especially in charging breaches of common law duties. For, in general, a court ought not to presume such a breach of duty without proof. And in those cases in which the plaintiff grounds his right of action upon a negative allegation, and, where, of course, the establishment of this negative is an essential element in his case, the burden devolves on him to prove the negative. 1 Greenl. Ev. § 78.

Such is the present case. The averment as to the defendant's breach of duty concerning the tobacco, is that the defendant “permitted it to deviate from the said route by railroad and to be transported part of said distance by water in boats.” Now if this word “permitted” is to be construed as the charge of some wrongful act by the defendant, the allegation is affirmative; and so the necessity on the plaintiff to prove it would be unquestionable. But if it is to be deemed—as I think it should be—merely an allegation of an omission of duty, then it is substantially a negative averment, on which, in the language of Professor Greenleaf, “the plaintiff grounds his right of action;” and still, I think, according to the rule above laid down and to the reason of the thing, it devolved on the plaintiff to prove the omission of that duty.

The plaintiff, in order to escape this conclusion, insists on the application of another rule, namely, that where the action is founded on a negative allegation, and the affirmative is peculiarly within the knowledge of the defendant, the burden is on the defendant to prove such affirmative. No doubt this is law. I do not think, however, that it is applicable to the point under consideration. It is mostly applied to charges of unlawfully performing things without a written license,—as to retailing liquor without a license.

755Here, if there is a license, the defendant is supposed to have possession of it; and if he does not produce it, it is fair to presume he has none. But in the case at bar, it ought to he presumed, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, that the defendant gave directions to carry the tobacco by rail to New York, and that those directions were in writing, and were delivered with the tobacco to the next carrier. The matter of such directions, therefore, was not peculiarly within the knowledge of the defendant.

It is also insisted on behalf of the plaintiff that, though no presumption of the breach of a common law duty on the part of a common carrier ought to be indulged in the absence of the evidence, yet when the plaintiff proves, as in this case, the loss of his goods, the burden of accounting for that loss devolves on the carrier. This is undoubtedly the general rule; but I think it is inapplicable to the present case. It applies to losses happening while the goods are under the care or control of the carrier; and it should not be extended to cases of loss after the carrier has taken the goods to the proper place, and delivered them to the proper person. Here, I repeat there is no evidence that the defendant engaged to carry the goods beyond Columbus, Ohio. The goods were lost at sea hundreds of miles beyond the eastern terminus of the defendant's road. The proof of such a loss, in my opinion, does not cast on the defendant the burden of accounting for that loss. Upon the whole, I think the plaintiff cannot recover on this evidence. He may be non-suited if he please, else I shall find for the defendant.

The plaintiff submitted to a non-suit.

NOTE. So far as bills of lading and other writings are mere receipts, they may be contradicted by parol, but so far as the writing contains terms of a contract it stands on the same footing as other written contracts. Thus a bill of lading receipting goods as in good order and well conditioned, may be contradicted by showing that their internal order and condition was bad, and any other fact erroneously recited. 1 Greenl. Ev. § 305, and notes. As to how far bill of lading is a contract, and how far a receipt, consult 1 Par. Shipp. & Adm. 190, 191, and notes; 3 Kent, Comm. 208; The J. W. Brown [Case No. 7,590], and cases cited; The Wellington [Id. 17,384]. As to the shipment, it is not conclusive evidence between the original parties. Grant v. Norway, 10 C. B. 665; Bates v. Todd, 1 Moody & R. 106; Berkley v. Watling, 7 Adol. & E. 29.

Though it appears to have formerly been the general rule that the contract must show on its face, that a person other than the executing party is the principal, or such principal is not bound, yet this would seem to hold now only in cases of solemn instruments under seal; and the authoritative rule now is that where the agent makes a contract, apparently in his own name, but really for his principal, his principal is liable. The difference being that the agent also makes himself personaily responsible. Mr. Justice Story says “there is no doubt that parol evidence is admissible on behalf of one of the contracting parties to show that the other was an agent * * * although contracting in his own name, so as to fix the real principal.” Story, Ag. § 270; also Id. §§ 110, 147, 160–162, 269, 392; 2 Smith, Lead. Cas. 226, and cases cited; Chit. Cont. (11th Am. Ed.) 149, note o; Id. 303, note o; Id. 309, note h; Higgins v. Senior, 8 Mees. & W. 834; Dykers v. Townsend, 24 N. Y. 57.

Mr. Parsons, in his work on Contracts (volume 1, p. 55,) states the general rule to be, “Parol evidence may always be admitted to charge an unnamed principal; but not to discharge the actual signer.” Consult also notes to same page, and page 549. Common carrier under special contract limiting his liability has no authority to contract with next carrier for a limited responsibility. Babcock v. Lake Shore & M. S. R. Co., 49 N. Y. 491. Effect of marks showing ultimate destination and using printed blank adapted to through contract. Id.

Where a common carrier contracts for the transportation over his route and delivery to connecting line, the fact that the contract fixes the price for the entire carriage does not make it a through contract, so as to entitle the succeeding carriers to the benefit of exceptions from liability contained in the contract. Aetna Ins. Co. v. Wheeler, 49 N. Y. 616. In a contract by a carrier to transport and deliver to a point beyond its own line, an exception as to liability extends to connecting lines who share the freight. Maghee v. Camden & A. R. Transp. Co., 45 N. Y. 514. Under an agreement to carry freight to a point beyond the terminus of its own line, a railroad company is liable for the default of a connecting line; but the mere receiving goods marked for such a point only binds the carrier to deliver to the next carrier. Root v. Great Western R. Co., 45 N. Y. 524.

For an elaborate discussion of the liability of common carriers on through bills of lading, and what constitutes a through bill, and under what circumstances a carrier is discharged from further liability by delivery at his own terminus to a connecting carrier for further transportation, consult Woodward v. Illinois Cent. R. Co. [Cases Nos. 18,006 and 18,007], and cases there cited; also a recent opinion by the U. S. supreme court. Railroad Co. v. Manufacturing Co., 16 Wall. [83 U. S.] 318. The rule adhered to by the Illinois supreme court is that a carrier receiving goods marked beyond his own route is liable for their delivery at their ultimate destination. Illinois Cent. R. Co. v. Copeland, 24 Ill. 332; Same v. Johnson, 34 Ill. 389; Same v. Frankenberg, 54 Ill. 88.

1 [Reported by Josiah H. Bissel, Esq., and reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

Google.