Case No. 3,288.

COUSE et al. v. JOHNSON et al.

[4 Ban. & A. 501;1 16 O. G. 719; Merw. Pat. Inv. 363.]

Circuit Court, W. D. Pennsylvania.

Sept. Term, 1879.

PATENTS—EXPANSION OF CLAIM—PATENTABLE INVENTION.

1. The patentee's exclusive right is enforcible only within the limits of his own definition of his invention. What he has not distinctly claimed, much more what he has not claimed at all, cannot be injected into his claims, even to save the patent.

[Cited in Delaware Coal & Ice Co. v. Packer. 1 Fed. 852.]

6522. The application of old mechanical devices, without material change, to a use in which they were not before employed, but which was known and had been practised, does not constitute a patentable invention.

[Cited in Brown Manuf'g Co. v. David Bradley Manuf'g Co., 51 Fed. 227.]

3. It is not invention to make the legs of a stove long enough to allow a lamp to be placed under it, without touching it.

[This was a bill in equity by Lucius H. Couse and others against Grove H. Johnson and others to restrain the alleged infringement of letters patent No. 45,957, granted to W. B. Billings, January 17,1865.]

Sturgeon & Hallock and B. F. Lee, for complainants.

George S. Prindle and Bakewell & Kerr, for defendants.

MCKENNAN, Circuit Judge. I am unable to agree with the ingenious counsel of the complainants in his construction of the principal claims of the patent in controversy. “Nebulous” as they are, they ought not to be expanded constructively beyond the limitations which the patentee has imposed upon them, so as to cover subsequent improvements in an art in which the invention claimed was, at most, only a step in advance. The patentee's exclusive right is enforcible only within the limits of his own definition of it. What he has, then, not distinctly claimed, much more what he has not claimed at all, cannot be injected into his claims, even though that may be necessary to save his patent.

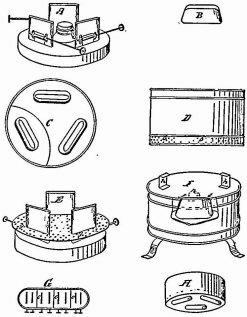

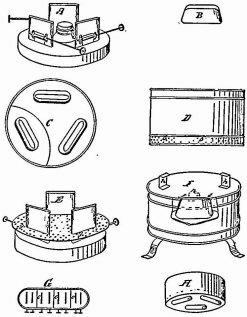

The first claim is for “the use and adaptation of the body or sides of the stove or range D to serve as and perform the office of a flue or chimney over the lamp or oil-holder A, substantially as described, and for the purposes set forth.” It is urged that this is to be regarded as a claim for a combination of three elements, to wit: the parts of the stove or range D above the air-guide diaphragm, with its elongated air-guides conforming to the wick-tubes, and the lamp. Whether the specification might warrant such a claim, it is not necessary to consider, but such is not the import of the claim, as the patentee has chosen to construct and limit it. It has exclusive reference to the cylinder to be placed on the top of the lamp, and to its adaptation to a single defined purpose, viz., to perform the office of a chimney. When this is done, the object contemplated by the claim is completely fulfilled, and no other part of the invention, which does not necessarily pertain to the special office stated in the claim, can be considered as embraced in it. Now, the functions performed by a flue or chimney over a lamp in an oil-stove are to create a draft of air to carry off the products of combustion and to direct the heat to the top of the chimney. All these functions are exclusively performed by the cylinder described in the patent, and hence no other device can be properly included in the claim. Now, the employment of a chimney over a lamp filled with kerosene oil and other combustible fluids, and for all the purposes indicated in this claim, is not new. It is unnecessary to analyze the numerous exhibits in the case, or to refer to them. It is sufficient to say, that it is shown in the patents of Fish, of Eddy, and of Clinton, and in the Dietz lamp, all of which antedate the plaintiffs' patent, and, therefore, anticipate this claim.

The second claim is for “the attaching of one or more air guides, cones, or deflectors in the diaphragm C, and the adjustment of the same in the stove or range F, substantially as described, and for the purposes set forth.” The following clause is all that the specification contains touching this claim: “The device for guiding the air into the flame, and to be placed over the wick-tubes, is shown in drawing B. These air-guides I fasten into a diaphragm about one fourth of an inch larger in diameter than the lamp A. The relative position of the air-guides in the diaphragm should be the same as that of the wick-tubes in the lamp A.” [See drawing C.]2 Drawing B represents an air-guide of oblong shape, and nowhere else in the patent is there any specific indication of its intended form. The claim is not limited to an air-guide of this form, and the specification does not assign any peculiar merit, or claim any new result, as the product of its conformation. No particular form of air-guide, then, can be considered as an essential part of the invention. Barry v. Gugenheim [Case No. 1,061]. The attaching of one or more air-guides to the diaphragm, and their adjustment in the stove, are the only features of the alleged invention claimed. How the air-guides are to be attached, the specification does not direct, otherwise

653than that they are to be “fastened into the diaphragm.” They are to be adjusted with reference to the location of the wick-tubes, over which they must be placed, so that the corners of the latter will be on a level with the lowest point in the slot or mouth of the air-guides.

It is not saying too much to affirm that the subject of this claim is of, at least, doubtful patentability, and that, in view of the vagueness of the specification, the patentee cannot make a valid claim to it; but, in consideration of the state of the art, I am satisfied that the matter claimed is not novel. It is embodied in several of the devices exhibited in the defendants' proofs, which are prior in date to the complainants' patent. Nor is the effect of the exhibits upon any of the claims of this patent averted by the fact that the patentee proposed to use his device exclusively as a stove and to employ kerosene for combustion, while some of the exhibits were intended for use as illuminating lamps in which alcohol or other combustible fluids were to be burned. The use of kerosene oil to produce both heat and light was not new, nor is any new function performed by the devices employed by the patentee to feed the lamp-flame with air, and to promote and govern the escape of the products of combustion. The application of old mechanical devices, without material change, to a use in which they were not employed before, but which was known and had been practised, does not constitute a patentable invention. Bean v. Smallwood [Case No. 1,173].

The third claim is for “the arrangement of the diaphragms C and g, g, thus forming an air-chamber between the oil-holder and stove or range, substantially as described, and for the purposes set forth.” Between these diaphragms, a space is left about one-half inch in height. This constitutes a chamber into which the air is admitted through perforations in the lower diaphragm, or in the body of the stove at its lower end, and the object is to interrupt the radiation of heat from the burners to the oil-holder below. An air-chamber or receptacle for air around the wick-tubes, and below the burner, is an indispensable adjunct to every petroleum-burning lamp, to supply the air needed for combustion. Hence it is found in most of the exhibits produced in evidence, and, doubtless, its contemplated use was as a reservoir of air to supply the burners; but, at the same time, it “prevents the heat from being thrown” upon the oil-holder. It is the same device, operating in the same way, and producing the same result with that embraced in this claim, and, therefore, the complainant cannot appropriate it as his exclusive property.

The fourth claim is for “a non-conductor of heat used as a packing between the stove and the oil-holder, arranged substantially as described and set forth.” Referring to the specification, it is plain that this is merely an alternative of the third claim. It expressly says so, and it contemplates only the substitution of a solid non-conductor for the air relied upon in the preceding claim. Its direction is to “fill the space between the diaphragm C and g, g, with a slab of corkwood, or pack it with granulated cork, asbestus, or any similar non-conductor of heat adapted to the purpose, leaving an opening under each of the air-guides for air.” It is obvious that water is not the equivalent of either of the non-conductors contemplated, because its use as they are directed to be used, is utterly impracticable. The air-chamber could not be filled with water, because it would not retain any of it, and if the air-chamber could be thus filled, its indispensable use as a means of supplying the burners with air would be effectually precluded. Water, then, contained in an open vessel placed on top of the oil-holder, is not an infringement of this claim, limited as it is; but, even if it were, its use is fully warranted by a similar prior use of it in vessels outside of the air-chamber, as shown in the Clinton and Custer exhibits.

The fifth claim is for “the insulation of the lamp or oil-holder by non-contact with the heater, stove, or range, substantially as described and set forth.” In simple phrase, the import of this is, that the body of the stove and the oil-holder are to be made in detached parts, which are not to be placed in contact with each other. “Insulation” is effected by making the legs of the stove long enough to allow, the lamp to be placed under it, without touching. The object is to avoid the transmission of heat from the stove to the oil-holder by conduction. To call this invention, is to misapply the term. The means of effecting the desired result are so obvious that it does not require ordinary mechanical skill to devise and apply them. But, in the respondents' stove, it is not sought to avoid contact between the flue or chimney and the oil-holder. To the former are attached not less than three metallic legs, which extend downward and rest upon the top of the oil reservoir. The two parts are thus directly in contact, but the heat transmitted through the legs is intercepted by a body of water which surrounded them in a trough aranged upon the top of the oil-holder. Thus there is no infringement of the claim.

The bill is dismissed at the costs of the complainants.

1 [Reported by Hubert A. Banning, Esq., and Henry Arden, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

2 [From 16 O. G. 719.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.