Case No. 3,155.

COOK et al. v. ERNEST et al.

[5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 396;1 1 Woods, 195; 2 O. G. 89.]

Circuit Court, D. Louisiana.

March, 1872.

PATENTS—“TIES FOR COTTON BALES”—UTILITY—PRESUMPTION—EXTENSION—DECISION OF COMMISSIONER—ANTICIPATION—INFRINGEMENT—INJUNCTION.

1. It is competent for a party to sue for an infringement of any one of the separate and distinct inventions that may be covered by his patent.

3862. The fact that other devices, superior to that covered by complainants' patent, taken as a whole, have been invented, and have driven the latter out of use, does not prove or tend to prove that such invention lacks utility, as the law uses that word.

3. The presumption, created by the issue of letters patent, that the patentee was the first and original inventor, is greatly strengthened by the extension of the patent, especially when the extension is resisted on the ground of want of novelty.

4. While the decision of the commissioner of patents is not entitled, upon this question, to the force of res adjudicata, yet it is a determination entitled to the highest respect of the courts, and should not be reversed except upon the most satisfactory proof.

[Cited in Odell v. Stout, 22 Fed. 161.]

5. The open slot in the metallic cotton-bale tie patented to Frederic Cook, March 2, 1858, was not anticipated by an elongated open ring, such as is used for fastening parts of chains together. No use to which the latter could naturally be applied would suggest the open slot in a rectangular flat buckle for the introduction of a flat band sidewise. Said invention was not anticipated by the English patent to George Hall, No. 2561, A. D. 1801.

6. The buckle described in the English provisional specification of Pilliner, A. D. 1856. was not described in such terms that the public could construct and put it to the use designed by Cook without further invention.

7. The fact that defendant has taken out patents for other improvements relating to the same subject is no reason why he should not be enjoined from infringing upon the improvement covered by complainants' patent.

8. The writ of injunction issues on the principle of a clear and certain right to the enjoyment of the subject in question, and an injurious interruption of that right, which, on just and equitable grounds, ought to be prevented.

9. Where complainants produced their patent; proved an uninterrupted use of the invention, without infringement, for eleven years; had established their patent by an action at law, in which every defense known to the law might have been set up; and had obtained an extension of the patent in the face of vigilant and interested opposition, a preliminary injunction was granted.

10. Property in a patent is just as much under the protection of the law as property in land. When the owner has made good his claim to his patent, and shown an infringement of it, it is the duty of the courts to give him the same relief meted out to suitors in other cases.

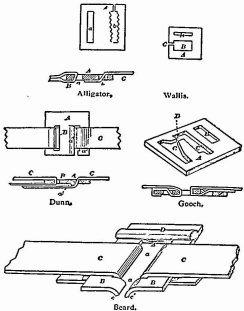

In equity. Motion for provisional injunction. Suit brought [by Frederic Cook and James J. McComb], upon letters patent [No. 19,490], for “improvement in metallic ties for cotton-bales,” granted Frederic Cook, March 2, 1858. and extended for seven years from March 2,1872, an equitable interest in which was conveyed to James Jennings McComb. There were six suits: One against Frederic B. Ernest and Frederic Ernest, agents for the sale of the “Gooch” tie; one against John S. Wallis, manufacturer of the “Wallis” tie; one against William Chambers, manufacturer of the “Alligator” tie; one against George Norton, M. O. H. Norton, and Arthur L. Stuart, agents for the sale of the “Dunn” tie; one against Andrew Stewart, William Stewart, Hugh Stewart, and A. D. Gwynne, agents for the sale of the “Beard” tie; and one against George Brodie, manufacturer of the “Brodie” tie, and defendant in the suit of McComb v. Brodie [Case No. 8,708]. The nature of the invention and the claims, together with engravings of the Cook and Brodie ties, will be found in the report of the latter case.

The accompanying engravings will illustrate the various ties sold by the defendants.

In the “Alligator,” “Wallis,” and “Dunn” ties, one end of the band was passed through the closed slot, and turned under, while the other end was first bent and then passed through the slit into the open slot. In the “Gooch” tie, the end which formed the fastening was bent and passed through the opening, D, into the slot, C, around the bar, A, and back and over the outer bar. In the “Beard” tie, both ends were bent and passed through the opening into the slot.

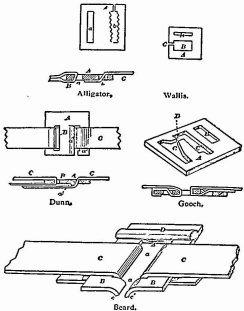

The accompanying engraving represents No. 16 of the drawings of Hall's English buckle, patented in 1801; and which, it was insisted by the defendants, anticipated the invention set forth in the third claim of the Cook patent.

Randolph, Singleton & Browne, J. A. Campbell, and S. S. Fisher, for complainants.

Clark & Bayne and Lea, Finney & Miller, for defendants.

WOODS, Circuit Judge. The bill states, in substance, that complainant, Cook, prior to March 2, 1858, was the original and first inventor of a certain new and useful improvement in metallic ties for cotton-bales, and which had not been known or used before his invention, nor been in public use before his application for a patent therefor.

387That on the day and year aforesaid, letters patent were issued to him for said invention by the proper department of the government of the United States, granting to him and his assigns, etc., the exclusive right of making, using, and vending to others his said invention. That on January 22, 1872, before the expiration of the original term of said letters patent, the said Cook contracted and agreed, in writing, to convey to his co-complainant, McComb, for a valuable consideration, all his right and title in said letters patent for the extended term thereof, if the same should be extended by the commissioner of patents, which agreement was duly recorded in the patent office. That on January 31, 1872, said Cook filed in the patent office a disclaimer to so much of said invention set forth in the letters patent as were embraced in the first claim of invention therein, which disclaimer was recorded according to law. That on February 17, 1872, the commissioner of patents renewed and extended said letters patent for the term of seven years from and after the expiration of the original term of fourteen years—to wit, from March 2, 1872.

That during the original term of said patent a suit was brought, on the law side of this court, by Mary Frances McComb and James Jennings McComb, the then owners of said patent, against one George Brodie, for an infringement thereof, which was tried before a jury at the November term, 1871, of this court—to wit, in March, 1872; that much testimony was introduced on both sides of said cause; the defendant denied the patentability of said invention described in the third claim, and the scope thereof, and denied infringement, and set up a claim in reconvention against the plaintiffs for the infringement of a patent issued to him on March 22, 1859, for an improved metallic band for baling cotton, and claimed that the buckle which he had made and sold was covered by his own letters patent; that the jury found, the issues joined for the plaintiffs, and rejected the claim in reconvention of the defendant That since the date of said extension the legal title to said letters patent has been vested in Cook, subject to the equitable rights of McComb, under the contract aforesaid; that the improvement specified in the third claim is of great value; that said claim has been applied by complainants to use, and introduced into the market, to the great advantage of the public.

That defendants, without consent of complainants, and in violation of their rights in said letters patent, have made, used, and vended to others to be used, and are now making, using, and vending to others, and are preparing to continue to do so, metallic ties for baling cotton, containing the invention set forth in said letters patent and claimed in the third claim of invention—that is to say, the slot described in the specification of said letters patent, cut through one bar of the clasp, which enables the end of the tie or hoop to be slipped sidewise underneath the bar in the clasp, so as to effect the fastening with greater rapidity than by passing the end of the tie through endwise, and that defendants have a large quantity of said ties, so constructed, in their possession, which they are preparing to sell, without consent of complainants, and in violation of their rights. That defendants have been requested to desist from making and vending said ties, and have been notified of complainants' exclusive rights as aforesaid; but, disregarding complainants' rights, have combined with others to make, use, and vend said ties. The bill prays for an account of profits and damages, and for injunctions, both provisional and perpetual, against defendants.

The case is now submitted to the court on the motion of complainants for a provisional injunction, after reasonable notice to defendants, who appear by counsel, and resist the motion. To sustain their motion, the complainants introduce the letters patent to Cook; the extension by the commissioner of patents; the contract of Cook with McComb, assigning to him the right of Cook in the extension; a certified copy of the examiner's report on the application of the extension of the Cook patent, and of the reasons of opposition to the extension filed by William Chambers; the testimony on said application; the affidavits of M. B. Muncy, Frederic Cook, F. B. Parkinson, James J. McComb, and William Clough; and the record in the case of McComb v. Brodie [Case No. 8,708], on the law side of this court From this evidence, it appears that McComb has the equitable title and Cook the legal title to the extension of the letters patent originally issued to Cook.

The schedule accompanying Cook's original patent discloses that the patent was intended to cover three separate and distinct inventions; (1) A friction buckle or clasp, represented by figures 1, 2, and 3, showing the different views of it for attaching the ends of iron ties or hoops for fastening cotton-bales and other packages. (2) The manner of looping the ends of the iron ties or hoops into a buckle, by the form of which they are prevented from slipping, by friction, when the strain of the expansion of the bale comes on the ties. (3) The slot cut through one bar of the clasp or buckle, as shown in the diagram, which enables the end of the tie or hoop to be slipped side-wise underneath the bar in the clasp or buckle, so as to effect the fastening with greater rapidity than by passing the end of the tie through endwise.

As already said, the bill complains of the infringement of the third claim only. The device covered by this claim is so clearly stated as to need no explanation. The affidavit of Cook shows that in 1857 he commenced the manufacture of ties according to his invention, which was patented to him

388in March, 1858, and that up to 1861, when he sold his patent to one A. O. Sturdevant, he had made and sold a number sufficient to bale twenty thousand bales of cotton; and he exhibits with his affidavit one of the ties made, according to his invention, in 1857. The affidavit of McComb shows that, since 1856, he has been engaged in the enterprise of introducing metallic ties for baling cotton; that in 1859 his attention was called to a device said to be the invention of one Taylor, which was simply a square buckle with an open side, through which the loop-end of the band could be-passed edgewise; but, on inquiry at the patent office, he learned that the open buckle was the invention of Cook, who had taken out a patent for it March 2, 1858; that he afterward invented a modification of the form of the mortise in the buckle, now generally known as the “arrow tie,” and in 1861, through an intermediate assignment; his wife, Mary Frances McComb, became the owner of the device patented by Cook; and, by uniting his own with Cook's invention, produced what is known as the “arrow tie:”

That in 1861 he went to England and made arrangements for shipping large quantities of bands and lies as soon as the blockade, then existing, was raised; which did not occur until 1865, when he at once commenced shipping his ties to each of the southern ports, and has continued to do so until the present time, and is prepared to supply fully the demand for iron ties in this country. That the first open infringements of the open-slot tie were in 1869, and they have increased, so that in 1870 one-third of the ties in competition with the arrow tie were open-sided, and in 1871 the entire importation was open-sided. That he has frequently and constantly notified infringers that they would be prosecuted, and has only refrained from so doing by the fear of impairing his credit in England, where litigation in reference to patent rights is much dreaded. Nevertheless; he did bring the suit of McComb v. Brodie [supra], which resulted as stated in the bill of complaint.

The affidavit of Muncy shows that the defendants are selling, in the city of New Orleans, ties with a buckle containing an open slot, one of which buckles is attached to the affidavit; and the affidavit of William Clough, an expert; is to the effect that the buckle sold by defendants employs the device described by Cook in the third claim of his letters patent. The documents filed, showing the extension of Cook's letters patent, show that, in applying for said extension, he disclaimed the first claim of invention in his original patent, and took out his extension for only his second and third claims. The certified records from the patent office also show that the extension of Cook's patent was opposed, among other grounds, because other parties, and not Cook, were the first to invent devices that rendered the use of iron bands practicable for baling cotton, and because Cook was not the first to use the slotted link for fastening metallic bands around cotton-bales.

The report of the examiner, in the application of Cook for an extension, states that, among the numerous American inventions of that class, none is found previous to that date (the date of Cook's patent) with an element of construction answering to his open slot Attention was, however, called by him to the English patent No. 2,561, A. D. 1801, granted to George Hall, for elastic fastenings for shoes, and also bands, garters, and ornaments for the knees, etc., showing buckles provided with open slots in numerous modifications of form and construction. On consideration of this report the commissioner of patents, as shown in the proof, extended the patent of Cook for the term, of seven years, as alleged in the bill.

This is the case as presented by the complainants, and it appears to me that it establishes the right of the complainants to the writ of injunction, unless the case is overthrown by the showing made by defendants. To resist the motion for injunction, defendants have offered a large number of affidavits; Many of these affidavits are to the effect that affiants have for a long time been engaged in the sale of metallic cotton-ties, and have never sold or seen in use a tie constructed according to the original patent of Cook. The affidavit of John S. Wallis, among other things, states that long before Cook's invention the use of open buckles, for the fastening of belts, bands, and chains, was common and public; and he illustrates his affidavit by attaching thereto what is popularly known as an open link, commonly used in trace-chains. Samuel H. Boyd testifies to the same effect; and Francis B. Fassman testifies that in April, 1871, he saw the open link, like the one described by Wallis, actually used to fasten the bands around a bale of cotton. Caleb S. Hunt also testifies that he is familiar with the use of links or buckles having slots for introducing rapidly an end-loop into the mortise, and has known of such use for forty years. The English patent to George Hall, referred to in the report of the examiner on the application of Cook for an extension, is also introduced to show want of novelty in Cook's invention. Numerous affidavits are introduced showing models and drawings of Frederick James Pilliner's provisional specification, No. 1,584 of English patents of 1856, showing a device which is claimed to be substantially the device of Cook's third claim. This device of Pilliner was intended for fastening military belts.

From this statement of the contents of the affidavits presented by defendants, it will be seen that Cook's invention is attacked on two grounds: want of utility and want of novelty. It is obvious to notice that all the affidavits intended to show want of utility

389referred to the three claims of invention, covered by Cook's patent, taken together. The affiants say that they have never seen the tie, as described In these three claims, used. But, as already stated, Cook's patent covers three separate and distinct inventions. It is competent for the complainants to sue for an infringement of any one of them, and in this case they complain only of the infringement of the third claim under the patent.

These affidavits do not show or propose to show that this claim is not a useful contrivance. The testimony clearly shows that the open slot for passing the end of the iron tie through the bar of the buckle sidewise is used on nearly all the ties now sold, which is conclusive proof of the utility of that part of Cook's claim. But, taking the three devices of Cook's patent as one combined contrivance, there can be no doubt of its utility. The testimony shows that ties made according to all three claims of his letters patent, sufficient to bale twenty thousand bales of cotton, were made and sold by Cook.

All the law requires as to utility is that the invention shall not be frivolous or dangerous. It does not require any degree of utility. It does not exact that the subject of the patent shall be better than anything invented before or that shall come after. If the invention is useful at all, that suffices. Hoffheins v. Brandt [Case No. 6,575]. To warrant a patent, the invention must be useful—that is, capable of some beneficial use, in contradistinction to what is pernicious, frivolous, or worthless. “Useful,” in the patent law, is in contradiction to mischievous; the invention should be of some benefit Cox v. Griggs [Id. 3,302]. The degree of utility is not pertinent to the question of the validity of a patent Tilghman v. Werk [Id. 14,046].

The word “useful,” in section 6 of the act of 1836 [5 Stat 119], and in section 1 of the act of 1793 [1 Stat 318], does not prescribe general utility as the test of the sufficiency of an invention to support a patent. It is used merely in contradistinction to what is frivolous or mischievous to the public; it is sufficient if the invention have any utility. Wintermute v. Redington [Case No. 17,896]. If the defendant has used the patented improvement or something substantially like it he is estopped from denying its utility. Vance v. Campbell [Id. 16,837].

Tested by these rules, the defense of want of utility is clearly untenable. The entire invention covered by Cook's patent was intended for a useful purpose. It can be and has been used for that purpose. It is not frivolous or mischievous. The fact that other devices superior to Cook's original device, taken as a whole, have been invented and have driven it out of use, does not prove, nor tend to prove, that his invention lacks utility, as the law uses that word.

The next defense presented by the affidavits is the want of novelty. This is confined to the third claim of invention—namely, the open slot for passing the end of the iron tie sidewise under the bar of the buckle. The issue of letters patent is prima-facie evidence that the patentee was the first and original inventor. This prima-facie case is greatly strengthened by the extension of the letters patent especially when, as shown in this case, the extension is resisted on the ground of want of novelty. While the decision of the commissioner of patents is not entitled upon this question to the force of res adjudicata, yet it is a determination entitled to the highest respect of the courts, and should not be reversed except upon the most satisfactory proof. The original presumptions of novelty and utility arising from the grant of a patent are strengthened by its extension. Whitney v. Mowry [Id. 17,592]. Upon an application for an extension of a patent, the law requires a very rigid scrutiny into the original claim of the patentee, as to the novelty and utility of the invention; and the extension strengthens the novelty and utility of the patent Swift v. Whisen [Id. 13,700].

To overthrow the case made by complainants, as to the novelty of the invention described in Cook's third claim, we have, first, the affidavits of Wallis, Hunt, and Fassman, showing the long anterior use of open links, like those attached to their affidavits, for connecting chains and bands. Upon the issue of novelty, testimony will not be received to show what might have been done with previous machines. Howe v. Underwood [Case No. 6,775]. It is not enough to defeat the novelty of an invention, that prior contrivances are produced, which might, with a little change, have been made into the patented contrivance, though not so intended by the maker. Livingston v. Jones [Id. 8,413]. When a useful machine is sought to be invalidated by an old one, made years ago, the testimony should be examined with care and caution to; ascertain whether the prior machine was actually and substantially the same. Hayden v. Suffolk Manuf'g Co. [Id. 6,261].

Changes in the construction and operation of an old machine, so as to adapt it to a new and valuable use, which the old machine had not are patentable, and may consist either in a material modification of old devices, or in a new and useful combination of the several parts of the old machine. Seymour v. Osborne, 11 Wall. [78 U. S.] 516. The link presented by the affidavits of Wallis and others is an elongated open ring. It is similar to a device long used for attaching the clevis of a plow to the double-tree, and it is exactly like the open links used by farmers for lengthening trace or other chains, by fastening two parts of chains together. The pretense that the prior use of this open link shows want of novelty, in Cook's third claim, is utterly untenable. It is a device designed to accomplish no such purpose as Cook's device, and is not adapted to that end. As used for uniting chains, a closed link is inserted

390in the slot of the open link. It was not designed to be used for the insertion of a hook or loop; for that could be done in a closed as well as open link, and with more facility in the former by putting the end of the hook or loop into the link than by passing it sidewise through the opening. It can, with more plausibility, be claimed that all closed buckles for fastening the ends of the metallic cotton-ties lack novelty, because iron links have been in use ever since the invention of chains. The fact that the link shown by Wallis' affidavit is in the form of a ring, shows that it was not designed for the introduction of flat bands, like cotton-ties, and no use to which it could naturally be applied would suggest the open slot in a rectangular flat buckle for the introduction of a flat band sidewise.

The next item of evidence to establish the want of novelty is the English patent to George Hall for elastic fastenings for shoes, bands, garters, etc., No. 2,561, A. D. 1801. This patent was used before the commissioner of patents to show want of novelty in Cook's third claim, in order to defeat the extension of his patent; but the effort was not successful. An examination of a model of Hall's buckle shows that it was not intended as a fastening for metallic ties or bands, and that it is so constructed that a metallic band can not be introduced sidewise through the open slot into the buckle, the stationary tongues in the buckle preventing the passage of any metallic bar or band. This, therefore, can not be claimed as an invention embodying the same principle as Cook's. The provisional specification of Frederick James Pilliner, No. 1,584 of English patents of 1856, shows a buckle which, as represented in the drawings of the experts who have attempted to give form to the device described in the specification, approaches much nearer the invention of Cook than the open link described by Wallis, or the device patented by Hall. It is a contrivance for fastening military waist-belts. It is not shown that any patent was issued for that device, and the proof does not show that it was described in any printed publication prior to Cook's invention, which the evidence shows was as early as 1857. But I am by no means satisfied that the device of Pilliner is identical with that of Cook. The provisional specification does not describe the device covered by Cook's third claim of invention. Remotely suggestive of it, it may be; but the illustrations given by experts do not agree, nor is the buckle described in such terms that the public could construct and put it to the use designed by Cook without further invention. Opinion of McKennan, J., in McMillin v. Barclay [Case No. 8,902].

We are, therefore, brought to the conclusion that defendants have not only failed to show the want either of utility or novelty in the Cook invention, but that they have not overcome the case made by the complainants as to the validity of the patent. The question of infringement of the third claim of the Cook patent, by a device the same in principle as that of defendants, has been recently tried by a jury on the law side of this court, resulting in a verdict for the plaintiffs. An inspection of the tie of defendants shows that it is substantially identical with the device of Cook, embodying the principle of his invention.

The defendants claim that to entitle complainants to an injunction they should have an undisturbed possession, and that an injunction will not be granted if it disturbs the existing condition of things. If by undisturbed possession it is meant that the patent has never been infringed, then an injunction could never be granted in any case; for, when there is no infringement, there is no necessity for, no propriety in the allowance of an injunction. The claim of Cook under his patent has never been attacked in the courts. He and those claiming under him have had undisputed possession of their property in their patent. They have continually asserted then rights under it, and have warned and threatened infringers. Notwithstanding their warning and threats, the latter have, as the evidence shows, continued to invade the rights of the patentee and his assignees. It is now claimed that an injunction should not issue, because it would disturb the existing order of things—that is, it would put a stop to infringements, and give a protection to the property of complainants, which the defendants will not voluntarily accord. In other words, the claim is, that because the defendants have been invading the rights of claimants for one, two, or three years, they should not be enjoined, lest the existing order of things should be disturbed.

The very purpose of the bill of complaint is to disturb the existing order and to induce a new order, by which the complainants may be protected in their property and rights. If the existing order of things is a good reason for refusing a preliminary injunction, it would be a still stronger reason for refusing a perpetual injunction on the final hearing; for the order of things would then have existed for a greater period of time. The rule laid down by Mr. Justice Woodbury in Perry v. Parker [Id. 11,010], is, that if respondent denies the complainant's title, and casts a shadow over it by evidence, the grant of the injunction must be delayed till the validity of the title can be tried under a proper issue in the case, unless the complainant can strengthen his claim beyond the mere patent by showing former recoveries in favor of it, quiet possession of it for some time, or frequent sales and use of it under him. In this case, the complainants have strengthened their claim by showing that their original patent has been extended in spite of strong opposition; that they have

391recovered upon their patent at law, when all defenses to its validity might have been made if defendants had so elected; and quiet possession and frequent sales and use, and a general acquiescence in their rights from 1858 to 1869, when open infringements first appeared.

Several patents issued to the different defendants for various improvements in cotton-ties have been introduced in evidence, and the rule of law is invoked that an injunction will not issue where the defendant holds under a patent Admitting this to be the correct rule, it has no application to this and similar cases; for none of the patents issued to the defendants cover the third claim of the Cook patent, for the infringement of which this suit is brought. The fact that these defendants have taken out patents for other improvements in cotton-ties, is no reason why they should not be enjoined from Infringing upon the improvement covered by complainants' patent. As well might a defendant to a bill for the infringement of a sewing-machine patent set up against a prayer for injunction the fact that he held a patent for a reaping-machine. The writ of injunction issues on the principle of a clear and certain right to the enjoyment of the subject in question, and an injurious interruption of that right, which, on just and equitable grounds, ought to be prevented. Hil. Inj. 818.

In this case the complainants have clearly established their rights under their patent; first, by the production of the patent itself; second, by the use of the patented article for three years immediately after the date of the patent, followed by the uninterrupted use of the assignee, without infringement, for eight years more; then, by an action at law, in which the patent was sustained, in which every defense known to the law might have been set up; and, finally, on the expiration of the original term of fourteen years, by proof of the extension of the patent in the face of vigilant and interested opposition. The defendants have been warned to desist from their invasion of the plaintiffs' rights. They disregard the warning, and continue to use complainants' property without their leave and without any compensation to them. If the rights of property so invaded were rights to land or other tangible estate, no court would hesitate for a moment to restrain the wrong-doer by injunction. The property in a patent is just as much under the protection of the law as property in land. The owner has the same right to invoke the protection of the courts, and when he has made good his claim to his patent, and shown an infringement of it, it is the duty of the courts to give him the same relief meted out to suitors in other cases. The defendants have had ample notice of this motion; they have been fully heard upon it I am convinced that the complainants have shown themselves entitled to the relief they ask, and that defendants have shown no good reason to the contrary. Injunctions will issue against all of the defendants.

[NOTE. For other cases involving this patent, see note to McComb v. Brodie, Case No. 8,708.]

2 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.