Case No. 2,593.

CHANDLER v. LADD.

[1 McA. Pat. Cas. 493.]

Circuit Court, District of Columbia.

March, 1857.

PATENTS—“LEVEL”—INTERFERENCE—NON-APPEARANCE OF PATENTEE—COMMISSIONER'S DECISION ON PATENTABILITY—PRACTICE ON APPEAL—INVENTION—PERFECTING—UTILITY—REDUCTION TO PRACTICAL USE.

[1. The rule of law requiring the commissioner of patents to lay before the judge the grounds of his decision, fully set forth in writing, touching all the points involved by the reasons of appeal from his decision, should be strictly followed.]

[2. The practice of the patent office in deciding as to the patentability of the invention before declaring an interference is proper, and such a decision, being important as to the subsequent steps to be taken by the parties, should be made with deliberation.]

[3. That, as between an invention claimed and an invention patented, there is a difference of construction which allows the use of the former in a different way from the latter, although it may rarely be required so to be used, does not render such difference fictitious, nor deprive it of the quality of a useful invention.]

[4. It is not necessary that the utility of a patented invention should be great. If the invention is an improvement at all, it is sufficient if it is of a different construction from former articles of the same kind, and of any use. Morgan v. Seaward, 2 Mees. & W. 544, followed.]

[5. It is not necessary that the thing for which a patent is sought should be the best of its kind, but if its intended use is practicable the invention is patentable. Many v. Jagger, Case No. 9,055, applied.]

[6. Although an invention has not been reduced to actual, practical use, yet, if it appears to be capable of such reduction, other things not opposing, it is patentable.]

[7. Where an interference has been declared between an invention claimed and a patent there-tofore granted, and the patentee, although notified, fails to appear or take testimony, it is error for the commissioner to refuse to grant the patent applied for because of failure to furnish unequivocal proof of priority of invention, and because that granting the application might restrain the patentee from making and selling his patented article, as the action of the commissioner could in no wise affect the patentee's rights, where it appears that the applicant furnished the best proof under the circumstances, his principal witness having died pending the hearing.]

[8. The first inventor has the prior right to a patent, if he uses reasonable diligence in adapting and perfecting his invention, although the second inventor has in fact perfected the same, and reduced it to practical, positive form.]

[9. The invention of Thomas A. Chandler for a level having a graduated circle with a rotating pointer (for which patent No. 17,023 was subsequently issued) possesses patentable novelty, and is prior to the invention for which patent No. 7,263 was granted to William Gr. Ladd, and to the invention for which Samuel Reed applies for a patent.]

[10. “Graduated,” in connection with said invention, has the meaning of “to mark with degrees, regular intervals, or divisions.”]

[Appeal from the commissioner of patents.

[On interference. Application by Thomas A. Chandler for a patent for a level having a graduated circle with a rotary pointer. Interference declared with patent No. 7,263, granted to William G. Ladd, Jr., April 9, 1850, and with the claim of Samuel Reed for invention of a similar level. From a decision awarding priority of invention to William G. Ladd, Jr., and to Reed, the applicant Chandler, appeals.]

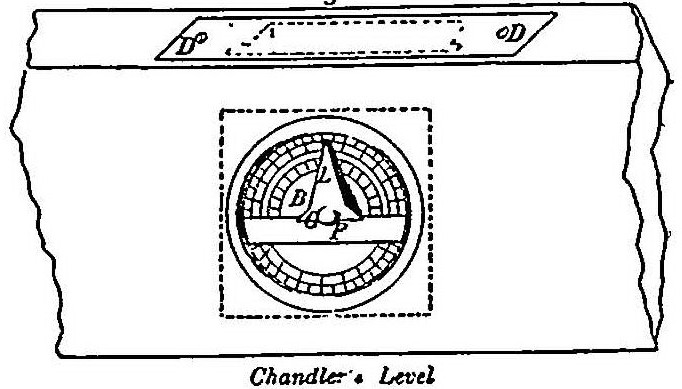

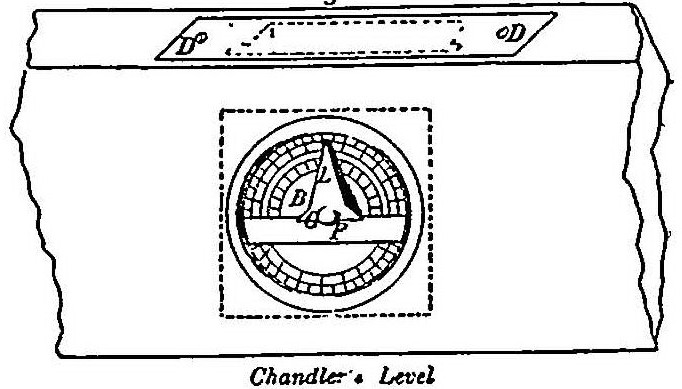

The question of the patentability of Chandler's device was reopened by the commissioner in his reply to the reasons of appeal. The discussion upon this subject will be readily understood by reference to the subjoined cuts, showing Chandler's level and the level patented to M. Georges, figured in the Brevet d'Invention, first series, vol. 52, p. 16, (plates,) which was principally relied upon by the commissioner as an anticipation of Chandler's alleged invention.

Fig 1.

In Chandler's level, a graduated circle with a rotating pointer or index finger L is placed on one of the sides of the stock and wholly within the faces of the level, so that either the top or bottom face of the instrument can be applied to the surface to be tested. By this arrangement the index can be caused to face front or back, as circumstances require, by simply turning the level on its longitudinal axis.

453

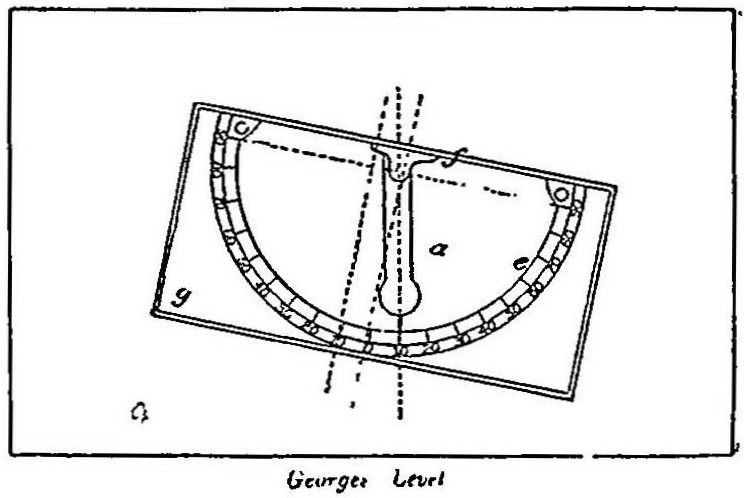

In the level figured in the Brevet d'Invention, the pendulum is hinged near the upper face of the instrument, and sweeps over a graduated semi-circle, so that the bottom face of the level must necessarily be applied to the surface whose inclination is to be determined. It was contended in behalf of Chandler that by reason of this difference in construction and arrangement his instrument can be used to greater advantage and under circumstances where it would be impossible to use Georges' device. As an illustration of the increased capacity of the instrument, a case was supposed where the level is placed in a confined space, from which it cannot be removed, and within which it cannot be turned around end for end. If, now, the spectator is at the back of the instrument, there will be no way in which he can obtain a view of the index on the Georges device so as to take the inclination. In the case of Chandler's device, however, he may apply the other face of the instrument to the surface by turning the instrument upon its longitudinal axis, thus bringing the index to the rear, so as to be visible to him in that position. The commissioner contended that the circumstances supposed had no real existence in practice; or, in other words, that they would so rarely occur that they could not affect the essential identity of the devices as ordinarily used. He further contended that the claim was not in any event properly limited to express the difference developed by this example. Upon the merits of the case, the commissioner contended that, with this understanding of the restricted nature of the invention, the proofs failed to show with sufficient clearness that Chandler had in view at the time he made his sketch A, upon which he relies to show his invention, the feature of novelty. The sketch in question was substantially as here represented.

The commissioner contended that this sketch does not necessarily show that Chandler had an entire graduated circle to be used as he now claims. There are only three graduation marks upon the sketch, and the commissioner described a variety of ways in which such an instrument might be used without involving the idea of the present invention. He noticed the fact, also, that the circle is eccentric to the sides, and that the index would extend below the face if the instrument were reversed. Ladd's patented level had other features of construction which rendered it independently patentable in the opinion of the commissioner. The patent subsequently issued to Chandler, in accordance with the decision of April 14th, 1857, No. 17,023. The patent to Ladd was granted April 9th, 1850, No. 7,203.

P. H. Watson, for appellant.

Examiners Lane and Baldwin, for commissioner.

MORSELL, Circuit Judge. On the 30th of September, 1851, the above-named Thomas A. Chandler filed his petition and schedule. The amended specification is dated the 27th day of May, 1852. It contains a full and particular description of the invention, and states the claim as follows: “What I claim is the combination of an entire graduated circle, provided with a pendulum and index, with the two parallel sides of the level stock, whereby I am enabled to apply either side of said stock to the surface whose direction is to be ascertained, and at the same time have the index facing the operator in whatever position he may be placed. I do not claim the level stock with its opposite sides parallel, nor the graduated indicating circle or dial, the indicator with two horizontal and one vertical pointer, nor the knife edge bearing upon which the indicator and pendulum are mounted, nor the pendulum, be cause separately and for other purposes they are well known; but they have never before been combined to form a level, nor has a level of any kind ever before been made capable of performing the functions of this combination. Therefore, I claim the level composed of the before-enumerated parts, in combination, whereby, among other things, either edge of the instrument may be used uppermost with its face or dial towards the operator, and when any two of the pointers are screened from sight by an intervening body, the third will indicate the inclination of the surface to which the instrument is applied, and the angles at the head and foot of a rafter will be indicated at the same time.” Interferences were afterwards declared with the patented claim of the said William G. Ladd, Jr., and with the claim of Samuel Reed. Mr. Ladd's claim, as appears from his specification, is in the following words: “What I claim as my invention, and desire to have secured to me by letters-patent, is a level for determining a horizontal and perpendicular line and the inclination of any slope with the same, constructed substantially as hereinabove set forth—that is, with a shallow cylindrical vessel or a tube in the shape of an entire ring, half filled with quicksilver, or other liquid, in combination with a graduated annular dial, whether a floating needle or indicator

454be used or not, the whole arrangement being substantially as hereinabove set forth.” Patented April 9th, 1850. For the purpose of deciding said issue made by the said interference, the said parties were allowed to take testimony, upon the return of which the commissioner, on consideration thereof, on the 21st of January, 1853, decided as follows: “This case came up for hearing on the 17th instant. The claim of said Chandler and Reed is for the combination of an entire graduated circle, furnished with a pendulum and index, with the two parallel sides of the level stock. On examination of the evidence produced on the part of said Chandler to show that the said improvement was used by him as early as the year 1840, it is found that the graduation of the circle was not made to appear in that evidence, and that, therefore, the invention of the combination claimed, of which that graduation is an essential element is not proved therein. The evidence on the part of said Reed being unaccompanied with proof of notice to the other parties of the time and place of taking the same, as required by the rules prescribed in such cases, is necessarily excluded. On the part of said Ladd, no evidence has been produced. By the records of this office, it appears that the application of the said Ladd for his patent—the same being for a level containing the equivalent of the combination claimed by the said Chandler and Reed—was filed on the 1st day of February, 1850; that the application of the said Chandler was filed on the 30th day of September, 1851, and that the original application of said Reed, of which his present application is a renewal, was filed on the 30th day of December, 1851. In view, therefore, of the evidence before the office, the priority of invention as between the parties to this interference is hereby awarded to the said William G. Ladd, Jr.” From this decision the said Thomas A. Chandler hath appealed as aforesaid and hath filed his reasons of appeal. The first of which is because upon the examination of the said application it does not appear that the improved pendulum level, claimed by this applicant as his invention, had been invented or discovered by any other person in this country prior to the invention thereof by him, or that it had been patented or described in any printed publication in this or in any foreign country, or had been in public use or on sale with this applicant's consent or allowance prior to the date of his said application, or that the said invention is not useful and valuable. Second. Because the level of William G. Ladd, Jr., was invented subsequent to that of this applicant, as is shown by the testimony in the ease, and the honorable commissioner therefore erred in ascribing to said Ladd the priority of invention. Third. Because it fully appears from the testimony that the invention of this applicant was anterior to that of Samuel Reed, and the honorable commissioner therefore erred in deciding priority of invention in favor of Reed. Fourth. Because no pendulum level known prior to the date of this applicant's invention possesses all the advantages or is capable of performing all the functions of his level.

In the commissioner's report dated 5th January, 1857, after the reasons of appeal in this case were filed, he says: “For the reasons of decision in this case, the office will refer to the accompanying copies of letters addressed to the applicant, such only being copied as are deemed sufficient to give all the grounds assigned by the commissioner for his decision. Little need be said here in addition to what has been said in these letters, the copies of which are made a part of this document. I will only add here the suggestion that the reason which may fairly be assigned why in the level referred to in the Brevets d'Invention more than a semicircle was not used was that the maker saw that the instrument would conveniently do all that was required of it without it. In fact, the first question that always arises in getting up any instrument of the class is. How long an arc do I want?—do I need the whole circle?—or, can I do with only a portion of it, and what portion? If these questions are not formally stated and dwelt upon, they are still practically and in effect necessarily asked and answered. In the old plumb-line quadrant of altitude, they resulted in the adoption of a quarter of a circumference. In the level cited in the Brevets d'Invention, for good reasons half the circumference was used, and for equally good reasons the other half was not used. In this point of view, the greater or less extension of the graduated arc upon the rectangular level stock, as in other instruments of the general class, seems to the office to be clearly a matter for the exercise merely of arbitrary choice and discretion, not involving any new invention. It will be seen that one of the official letters here copied proceeds on the supposition that a level in Rees' Cyclopaedia had been referred to in a former letter of the office. This was an oversight—the one really referred to being that in the Brevets d'Invention; and that part of the argument which is not appropriate to the last mentioned is of no special importance, though it would be regarded as having its weight in the absence of the closer reference given, me commissioner desires that this, and the letters to which he refers as a part, shall be taken for his reasons of the decision.” The rule of law declares that it shall be the duty of the commissioner to lay before the judge the grounds of his decision, fully set forth in writing, touching all the points involved by the reasons of appeal, to which the revision shall be confined. The irregularity of the course which it is desired thus to be pursued will at once be perceived by the commissioner

455to be something more than mere form. I have, however, examined the letters and their effect on the point of novelty, as far as it is understood to he in question in connection with any part of the issue, which is as much as under any circumstances ought to be here noticed. During the pendency of the application, the various objections and the nature of them were stated and insisted on by the commissioner. It seems, however, to have resulted, on the 24th May, 1852, in submitting the matter in controversy to the examination of four examiners, two of whom reported in favor of a claim according to the amendment and disclaimer suggested, which was afterwards substantially adopted by the appellant. The decision of interference followed shortly afterwards in these words: “In the matter of your (Chandler's) pendulum level, the feature in question covered by your claim has been decided to be patentable, and on the 18th instant notice was given to the party who filed the rejected application mentioned.” This decision as to the patentability of the invention has always, in the practical course of the office, been pursued before declaring an interference and putting the parties to the trouble and expense of obtaining proof; and certainly it was reasonable and right, and the decision should be with a deliberation becoming the subsequent important step necessarily to be taken by the parties to maintain their claims to priority of invention. There are a few letters subsequent to this event. The only one which it is important to mention is the one of the 22d of January, 1853, which awards priority of invention to William G. Ladd, Jr. It is difficult to understand what the commissioner meant by the letter of 11th of February, 1853. It seems to consider the patentability of the claim still open. Upon this state of the case, according to notice duly given of the time and place of hearing, the commissioner laid before the judge his decision and reply to the reasons of appeal, with the said reasons of appeal and the original papers and the evidence in the cause; on which occasion, an examiner appeared on behalf of the office, and the appellant by his attorney; and for the purpose of explaining the nature of the said invention, Mr. Lane and Mr. Baldwin, two of the examiners of the office aforesaid, were examined on oath before me; which evidence on said examination was reduced to writing, and will be sent with my decision. The parts only which are deemed most material will be here stated. Mr. Lane, in defining the term “graduated,” says: “It is a general term, used to signify the dividing of a line into parts which can be read off.” He states what he considers to be the difference between the graduated semi-circle and the entire graduated circle; that the difference of function in the latter is not of such importance, especially when considered in connection with the obvious nature of the means of producing it, as to constitute more than a colorable difference. His answer to the eleventh interrogatory is: “Both levels are in the same box; it is equally difficult to get both out into the air; and the fact about applying the level is partly owing to the fact that one has the entire graduated circle and the other only a graduated semi-circle, and partly to the fact that they are boxed up so that they cannot be got out.” The substance of the same question is repeated in the fifteenth interrogatory. In answer, he says there is no other material difference.

Mr. Baldwin, being next, examined, is asked to state the principle of the two levels. He answers: “The principle of operation is the same; that is to say, each will determine the inclination of a plane, by marking with the pendulum the degree of inclination on a graduated scale; but the instrument, with the entire circle graduated, will always show to the operator occupying one position the degree of inclination, while the semicircle must be reversed in determining the inclination of the same planes—the two opposite sides of a pyramid for example, and to see this registration the operator would be compelled to change his position, or the operator would be obliged to reverse the ends of the level in the case last supposed; and in some positions, where the level would be useful, this might be found impossible, as, for example, in a shaft or tunnel.” In answer to a question propounded for the purpose, he says: “If the invention of the entire graduated circle made the instrument operative, where the instrument with the semi-circle would not be, it would seem to present a patentable invention beyond question; and even if it operated better in some particulars than in others, the graduated circle, or an improvement on the semi-circle for the specific purpose to which the improved operation referred, might also be patentable.” To a question propounded for the purpose, he answers: “The model of Samuel Reed does not seem to have contemplated the use of the opposite edges of the level as parallel planes, but to have used sights on the top to determine the plane for long distances. If he did contemplate such use of his instrument, it is the same invention substantially as that of Chandler, with the exception of the substitution of the mercurial indicator for the pendulum. In William G. Ladd, Jr.'s patent, this instrument is substantially the same as Chandler's. Both of these cases would probably embrace the combination constituting the first clause of Chandler's claim. The model of James Eames does not involve the invention claimed by Chandler's first claim. M. Georges' level is limited to the semi-circle, and will of course not operate under all circumstances like that of either of those having an entire graduated circle, for the reasons given in my first answer.” He is asked: “Please examine the drawing marked ‘Exhibit A,’ and annexed to the deposition

456of M. L. Dunlop, and state whether it represents the combination claimed by the appellant in his first claim.” Answer: “The drawing represents a level having parallel sides, and a circle graduated by a marked division into parts—three of which indicate quarters of the circle—and a pendulum indicator, and of course it involves the combination embraced in the first clause of Chandler's claim.” Written arguments were made by the counsel for the appellant and on the part of the office, and the case was submitted. Regularly, and according to the usual practice, the only question which the present issue would present on this appeal, as arising before the commissioner, would be that of priority. The argument before me on behalf of the commissioner is on two grounds: First. That the invention as claimed is not patentable, for want of invention. Secondly. Because of priority in William G. Ladd, Jr.

The first reason of appeal involves the consideration of the question under the first head. It is in proof that the construction of the appellant's level is different, and capable of performing functions of which no level known to the commissioner was capable. This does not seem to be denied; but it is contended that this difference is not invention; that it is formal, not substantial; merely colorable. The argument of the commissioner seems to be intended to show that the objections are sustained. The commissioner takes the position that the office has stated that the level with the graduated semi-circle, the other elements of the combination being the same, enables the operator to measure the angle of inclination of any surface” with the index facing him, in whatever position he may be placed. This, in point of fact, seems to be inconsistent with what Mr. Lane, the examiner, has said in his testimony as a witness, in which he says that of two levels in all respects precisely alike, except that one has a semi-circle and the other an entire circle, the one with the circle can be applied to a given surface in a given place with the index facing towards the operator, so that he may see whether or not the surface is level; and the other level with the semi-circle cannot be so applied. The next position is that the appellant's description of his claim does not set forth the particular functions of the level, or any indication that it refers to aught else than a definition of the natural capabilities of the level in regard to the variety of positions it can assume; that it does not refer to the application of the level under obstacles or confinement, since, certainly, obstacles could readily be contrived to prevent its application to a given surface. The conclusion to which the commissioner comes on this point is: “It is certainly fan to apply the same rule of construction to the language which the office bas employed to define the extent to which the level with a graduated semi-circle is capable of assuming different relative positions.” To make his meaning more clear, the commissioner has given a very full amplification. He says: “The difference between the two levels is thus completely defined by this language, when taken in connection, as it was intended to be, with that of the claim, as also it is in the statement made by Mr. Lane before the court; and this difference or distinction between the two levels, so defined by the different extent to which, without obstruction, they are callable of assuming different relative positions,” he says: “I will for greater clearness call A; and aside from the question of the meaning of former language of the office, it is plain now what is meant by A. * * * Another point arises, and that is the advantage which the level with the entire graduated circle has, by virtue of the difference A (the principal element of which difference, as defined in the claim, is that it can be applied, supposing no obstruction, with either side of its stock to the surface) over the level with the graduated semi-circle, when we come to have the level confined in a space (a tunnel, for instance) from which it cannot readily be taken out, and in which it has so little room that it cannot be toned end for end. The special occasion of this kind I will call B. Now, the advantage which arises out of A when the occasion B occurs is palpable, and the office is by no means disposed to ignore it, supposing B to have a real existence. * * * If the occasion B do have to a material extent a real existence in practice, it shall impart importance to A; but if B do not have a real existence in practice, and is only a fictitious occasion, then A shall not receive importance from it.”

The point of the argument thus far appears to be for the purpose of showing by a construction fairly applicable to both levels, (for the reasons stated by him,) that In giving the description and definitions at the various times when he has been called upon to do so, he has been entirely consistent as to the semi-circle, intending to mean a limitation of its application to instances without obstruction. I have stated this part of the argument, not with any view to criticise it, but to show that a due respect has been paid to it. As to the question to which the commissioner considers himself finally brought—“that the feature of the invention in its combination is not real, but fictitious, because not known in fact in practice; that the occasion has not arisen in actual practice; and that it would not occur once in the lifetime of one level in a hundred or a thousand“—and as to the reply to the instance of the aqueduct and tunnel, the principles involved in this part of the argument cannot be acceded to. The fact of the difference of which the invention consists is certainly not fictitious. It has been looked upon; it has occular demonstration; nay, it has been admitted by the commissioner; and

457although it may not be an ordinary occurrence, that it is required to be so used, yet, even if used in the admitted rare instance, that would be no sufficient reason to deny useful invention. So with respect to the little difficulty a skillful workman would have in making it, one thing is certain—it never has been made or used in its present combination; and why, therefore, is it not a useful invention? The commissioner himself on a former occasion, and some of the examiners, have said the feature is patentable; and the able Examiner Baldwin has fully examined it, and has pronounced it, under the circumstances stated by him, to be patentable. And now I will state a rule of patent law which directly, in my judgment, bears on the case. In Norm. Pat. p. 23, § 4, quoting from Baron Alderson's opinion in the case of Morgan v. Seaward [2 Mees. & W. 544], it is said: “It is not necessary that the utility should be great; it is sufficient if the invention is an improvement at all. If it is of a different construction from former articles of the same kind, and of any use, that is sufficient. If a new description of steam-engine could be used where other engines would not answer, that would be sufficient; it need not be likely to come into general use.” This case seems to me to run on all-fours with the case before me, and I cannot help thinking that it may satisfy the commissioner that he has been in error on this point. There is still another case applicable to this point, to be found in Curt Pat (New Ed.) p. 37, footnote,—a decision of Mr. Justice Nelson in the case of Many y. Jagger [Case No. 9,055], in which the judge says: “To maintain a patent it is not necessary that the thing should be the best of its kind; but if the use for which it was intended is practicable, that is sufficient to sustain it as a useful invention.” I will add, in addition, that the law is well settled that although the invention has not been reduced to actual practical use, yet if it appear to be capable of being so reduced, it will be sufficient (other things not opposing) to entitle the party to a patent.

It now only remains to consider the question of priority of invention between the appellant and Ladd and Eeed. With respect to Eeed, he has offered no testimony legally, and therefore he may be considered out of the question. With respect to the other defendant (Ladd), he can carry his invention back only to the time of filing his specification on the 1st day of February, 1850.

In considering the testimony, it will be proper to notice the affidavit of Chandler, in which he states that he had relied upon the testimony of Calvin D. Bristol, late of the county of Dupage, Illinois, to substantiate his claim to said improvement in levels; but by a dispensation of Providence, the said Bristol departed this life in the month of September last past, and in consequence he was under the necessity of relying upon the testimony of M. L. Dunlop, who during the years 1837, 1838, and 1839 was head clerk for the contractors, Messrs. Hugunin & Brown, on the Illinois and Michigan canal, where his said improvement was first used, and who was frequently on the work and familiar with the machinery during the year 1840, after he had retired from the principal charge of the work, and is now acting justice of the peace in the said county of Cook. He has carefully examined the sketch marked “Exhibit A,” drawn by the said M. L. Dunlop, and purporting to represent his said improvement in pendulum levels; that this pen sketch is substantially a correct representation of a level constructed by him for the purpose of leveling the drilling-machines on the works of said Brown in the year 1840. The deposition of said M. L. Dunlop, which appears to have been regularly taken 22d of December, 1852, is as follows: That during the years 1837, 183S, and 1839, he was principal clerk for Messrs. Hugunin & Brown, contractors on the Illinois and Michigan Canal, at Eupotors, Illinois; that he was familiar with all the machinery used in their said work; he became acquainted with Thomas A. Chandler, the preceding deponent, in the fall of 1837, and the said Chandler was machinist and superintendent of the mechanical department in said work most of the time, until the deponent left the work in the month of September, 1839; and after that time, and during the year 1840, he was frequently on the work aforesaid, and frequently saw the said level as claimed to have been constructed by the said Thomas A. Chandler, of which the pen sketch annexed, marked “Exhibit A,” is a correct representation of said level as was used by the said Chandler to level the drilling-machines on said work—P P P being arms or pointers, C the circle. The stock was made of wood, while tfie pin and pointers were of iron. He understood at the time that said Chandler was the maker and inventor of said level, and that he fully believes that such is the fact. He was knowing to C. D. Bristol having charge of one of the drilling-machines on which said levels were placed. It is generally understood that the said Bristol died of cholera, at his residence in Dupage county during the month of September last.

The decision on the subject of the evidence, as before stated, is placed upon the ground that the graduation of the circle was not made to appear in the evidence; and the rule which he, the commissioner, says in his argument should be adopted is that the testimony on the part of Chandler ought to exhibit the most unequivocal proof that in the level described therein he had the difference A distinctly in view before the grant of a patent would be proper. Such

458proof, on a careful examination of the testimony, is clearly wanting. And this yery rigid rule should be adopted because of the peculiarity of the case in this particular—that granting the patent for the appellant's claim might have the effect of restraining Ladd from the right of making and selling his level. Now, in this, I think the commissioner is mistaken, because it is a well-settled principle of law that after the commissioner has granted a patent, and delivered it, nothing he can do afterwards can affect the patentee's rights under the patent. Ladd is a patentee. Again, Ladd is in the issue against the appellee, and, although duly notified, has failed to take any testimony, or even to appear and cross-examine the witness; nor does it appear that he was before the commissioner—certainly not before the judge—contesting or denying the sufficiency of the evidence on that or any other of the various grounds stated by the commissioner. What is then (not to say the legal but) the common-sense inference? Again, as before said, the act of the commissioner cannot affect Ladd's title under the patent, but the rejection against the appellant would be fatal. Again, it appeals from his affidavit that during the protracted investigation in this case he lost by death his principal witness. Further, Ladd's title, which it is admitted can be only carried back to the time of filing his petition, which is comparatively recent, is supported by only his own oath, and this, with the patent, is prima facie evidence only of his right, which may be repelled by a greater weight of evidence, whether offered as in the original order or otherwise. Better evidence than the nature of the case will admit of ought not to be required. The evidence in its nature as to this particular point is not so much for the purpose of showing that the instrument showing the invention was perfected and matured, as for showing the particular periods of the conception of the idea embracing the invention, and showing that it was then known. For perfecting and maturing the instrument, by which it could be reduced to practice, he had a right to make his experiments, if necessary, even for a greater length of time than taken in this case before filing his petition and specification, which, when done, should have relation back, so as to protect his priority. In the familiar case of Reed v. Cutter [Case No. 11,645], the plaintiff was a patentee suing for an infringement of his patent, and in which the court, among other things, decides as follows: “The clause of the fifteenth section now under consideration seems to qualify that right, by providing that in such cases he who invents first shall have the prior right, if he is using reasonable diligence in adapting and perfecting the same, although the second inventor has in fact perfected the same and reduced the same to practice in a positive form. It thus gives full effect to the well-known maxim, that he has the better right who is prior in point of time, namely, in making the discovery or invention.”

In this case the evidence offered in defense to show another to be the prior inventor was evidence in its character tending to prove the fact of prior invention, because it might be deemed sufficient by the jury. I trust I have thus shown that if the evidence would be sufficient were it as an original question, it certainly ought to be so considered in this-case; and then I have the concession of the commissioner that it would be deemed sufficiently suggestive to the mechanic or instrument-maker of any such pendulum level as that, for instance, in the Brevets d'Invention. “In other words, the office would say, as an original question, that it was sufficiently suggestive of a pendulum level in general.” The subject has been placed upon still stronger grounds—that the evidence does show unequivocally the entire graduated circle, and instances of the practical use of the instrument successfully. That the instrument about which the witness testified, and a rough sketch of which he gave, had been in useful operation for some time, is positively proved. As to the meaning of the term “graduated,” Craig's Etymological, Technological, and Pronouncing Dictionary is referred to, which gives it this definition: “To mark with degrees, regular intervals, or divisions.” It is contended in argument that Mr. Lane admits that the circle in Exhibit A is marked off into divisions by three marks (the fourth mark being screened from view behind the pendulum). It is plainly to be seen that it is; and it is thence concluded that, according to said definition, Chandler's original level did contain the feature of an entire graduated circle. The commissioner in his argument says that there is no proof to show that the sides of the pendulum bar were truly adjusted, so that the mean of their two readings would give a correct result. He says further: “This, then, is a level that manifestly presents no idea of using it with either side up; that is, with either side applied to the surface whose direction is to be ascertained.” The commissioner, in respect to this, is mistaken as to the facts. The Exhibit A represents the two parallel sides of the level stock. This is plainly shown by inspection and actual measurement, and demonstrated by a model level made in accordance with that sketch, and now before me. And it very satisfactorily shows, also, that it can be used with either side up; that is, with either side applied to the surface whose direction is to be ascertained. This error in point of fact no doubt contributed in a great degree to the incorrect conclusion of the commissioner's argument on this most important point of evidence, which would have been avoided if at the time of writing this part of the argument the sketch had been before him. To show more clearly that the rough

459sketch made by the witness, and a part of his testimony, has not been duly appreciated by the commissioner, see the testimony of Mr. Examiner Baldwin, hereinbefore recited, and a part of which I will here again repeat. He says: “The drawing Exhibit A of Chandler's testimony represents a level having parallel sides and a circle graduated by a marked division into parts (three of which indicate quarters of the circle), and a pendulum indicator, and of course it involves the combination embraced in the first clause of Chandler's claim.” And if I may be allowed again to repeat another part of the testimony of the same learned examiner as to the points of novelty and patentability of the claim in this case, having before him the various levels exhibited in this case, with the graduated circles and semi-circles, respectively, he said both were alike as related to the general principal upon which their operation depends—that is, the stability of the indicator under the influence of gravitation—while the stock and graduated circle are turned to accommodate themselves to the varied surfaces whose inclination is to be observed.

With the views which have been taken, I think the testimony fully supports the priority of the appellant in his claim aforesaid. And, upon the whole case, I think the invention aforesaid patentable, and that the decision of the commissioner in this case is erroneous, and ought to be reversed.

[NOTE. In accordance with this decision, patent No. 17,023 was issued to Thomas A. Chandler, April 14, 1857.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.