Case No. 2,275.

The BYRON.

ALBURY v. The BYRON.

[5 Adm. Rec. 240.]

District Court, S. D. Florida.

May 11, 1854.

SALVAGE—MAONIFYING SERVICES—FORFEITURE OF COMPENSATION—COSTS—RESTORATION OF VESSEL.

[1. Property libeled for salvage service is in the possession of the court, and can only be restored by its order. Neither dismissal of the libel nor satisfaction of the demand will operate as a restoration ispo facto.]

[2. Where a master claims as bailee of the owners, the court may refuse to restore the vessel to him, if satisfied from his past misconduct or present condition that he is an improper person to trust with the same, and that the interest of the owners will be jeopardized.]

[3. In such a case, the test as to restoration is, what, in the opinion of the court, would the owners themselves do, if on the spot, in possession of all the facts?]

[4. Wreckers who, under a pretense of making their best efforts to relieve a stranded vessel, keep her aground so as to enable them to render unnecessary service, and thus fabricate a case of meritorious salvage service, will forfeit compensation for real service rendered to which they otherwise would be entitled.]

[5. The master having been at fault, the costs should be charged to the vessel and cargo.]

[In admiralty. Libel in rem by John Albury and six others, against the bark Byron (Joseph H. Titus, master) for salvage.]

W. W. McCall, for libellant.

S. I. Douglas, for respondent.

MARVIN, District Judge. In this case, Albury, master of the wrecking schooner De Russey, and six other masters of wrecking vessels, consorted together, libel for salvage for services rendered to this bark and cargo, in lightening and getting the bark off from the reef, situated between Tavenier and Roderigues, known as the “Triangle Shoal,” on which she had run while on a voyage from New Orleans to Baltimore. The master has appeared and claimed the bark and cargo, as master thereof, and bailee of the owners, and has put in an answer. It having been reported to Captain Welch, resident agent of underwriters, that the bark had run aground in the daytime, after one of the wreckers had offered to pilot her out from inside the reef, where she had got, and that after getting aground, the master had declined the assistance of the U. S. steamer Corwin, engaged in the service of the coast survey, on the hearing he applied to the court and was admitted amicus curiae, under its 24th rule, to appear and defend the ship and cargo against the demand of salvage. He also prays the court to withhold any order to restore the ship to the master on account of his misconduct.

Two questions are presented by the case for the court's decision. First. Are the libellants entitled to salvage for their services, and if so, how much? Second. Ought the court under the circumstances, to order the bark and cargo to be restored to the master, that he may proceed on his voyage without any unnecessary delay, or detain the bark until time has been given to learn the wishes of his owners upon the subject?

I shall consider the last question first, and I shall state just what I conceive to be the law applicable to the question. In a proceeding in rem in admiralty, the court takes possession of the property, and it remains in its possession until some order for its restoration or delivery to the claimant is given. Neither a dismissal of the libel, not a satisfaction of the libellants' demands will per se operate to reinvest the claimant with its possession, but an order of the court is necessary to accomplish this end. The Phebe [Case No. 11,066]; Burke v. Trevitt [Id. 2,163]; La Jeune Eugenie [Id. 15,551]. Generally the libel being dismissed, or, the libellants'demand being satisfied, the order for restitution to the claimant

957is given of course, and without much inquiry into the claimant's right or title. But this arises from the fact, that the claimant's title rarely becomes a matter of controversy. But it is manifest, that it may become a proper subject of inquiry and the propriety of restoring to the claimant the possession even after the libel is dismissed, or the libellant's demand satisfied, may under certain circumstances, become a subject for very serious consideration by the court. Suppose for instance, in a suit for seaman's wages, or for salvage, or for bottomry, the libel should be dismissed, or the libellant's demand satisfied, and yet it should appear, that the ship had incurred a forfeiture for a violation of the revenue or neutrality laws, or the laws against the African slave trade; or that the goods had been smuggled; or it should appear, that the ship or goods had been piratically seized or feloniously run away with, can there be any doubt that in these and like cases, it would be the duty of the court to refuse to restore the property to the claimant, but to keep it to enable the government to proceed against it, in the first instance for the forfeiture, and in the second, to enable the real and true owner to recover his property? Or suppose the claimant be the master of the ship, and as such the bailee, and it should appear, that he had voluntarily cast his ship away, or had bored or burnt her, or run away with her, or had embezzled a part of the cargo or had colluded with salvors, or had become insane, or had fallen into such beastly habits of drunkenness, as to render him an unsafe guardian of the property, or, into such habits of brutal and ungovernable passion as to render it unsafe for the crew to perform the voyage with him—can there be any doubt that in these, and the like cases, it would be the duty of the court to withhold from him the possession of the property and preserve it for the owner? I have no doubt that such would be the duty of the court In these cases, no question of jurisdiction is involved, for the property is subjected to its jurisdiction by the libellant's suit, and its jurisdiction does not end with the suit, for we have seen, that it requires an order to restore or deliver the property to the claimant. But the question is one of right between a false claimant in court, and the true owner not in court, in the first instances, and in the second instance between an untrustworthy master or bailee in court, and the betrayed and injured real absent owner. In the case of the British brig Isabel [Case No. 7,098], decided in this court in 1840, and in the case of————decided in 18—, the court withheld the property from the master on the ground of a voluntary stranding.1

In refusing to redeliver the ship and cargo or their proceeds, to the master on account of his unfitness to receive them, the court does not act upon the notion of inflicting upon him any penalty or punishment for misconduct, but upon the idea of preserving the property for the real owner, and his conduct is no farther a proper subject of investigation, than to enable the court to determine whether he will probably prove a safe keeper of the property and account for it, to the owners in case it should be delivered to him. The presumption of the law is in his favor, and it requires proof to overcome this presumption. In determining upon the sufficency of the proof, it is to be considered, that not every act of misconduct or omission of duty by the master will authorize the conclusion, that he will prove so faithless to his trust in the future, as to endanger the safety of the property if recommitted to his keeping. But it is to be borne in mind, that he has been appointed by the owners of the ship and they are responsible to the owners of the cargo for his conduct, and, unless the court should be of the opinion, upon a full consideration of all the facts, that the owners would themselves, if on the spot, and in possession of a knowledge of the facts, and uninsured, unhesitatingly remove the master, upon the idea, that the property would be unsafe in his hands, the court ought not to withhold the possession of the property from him. But, if the court should be of the opinion, that the owners, if present, would, with the evidence before them, remove the master, on the idea of the insecurity of the property in his hands, and the court should, nevertheless restore the property to him, and thereby enable him to destroy, embezzle or run away with it, it would, in my judgment, be guilty of a plain and manifest dereliction of duty. See the case of La Jeune Eugenie [Case No. 15,551].

To try this case now by the rule above laid down, the amicus curiae alleges that the master “caused the bark to go ashore, and be cast away.” The charge is vague and general, but it was evidently intended to convey the idea, that he voluntarily cast her away. If this charge were made good by the proof it would clearly be the duty of the court to withhold from the master the vessel and cargo, because it would be a fact from which the court would infer a probability that the property would be insecure in the hands of the master, and that the owners, if uninsured and present, would, on the same ground, remove him. But I think the charge is not proved. It seems to have been based upon the unexplained circumstances, that the ship was seen beating to windward inside and on the line of the reef, for some three or four hours, in the daytime, that the wreckers offered to pilot the bark out, but the master declined their services; and when he got aground, he declined the offered assistance of the government steamer Corwin, and accepted the assistance of the wreckers. These circumstances, unexplained, would, in my judgment, be sufficient to overcome the presumption of the captain's innocence and to establish the charge against him. But the the testimony of the mate, three of the men,

958and one of the wreckers so explains these circumstances as to make them consistent with his innoceace. The mate says, that he had the deck during the morning watch, from four to eight, the captain being below, that soon after daylight he discovered the Florida land and saw a large ship at anchor and several wrecking vessels, but did not think the reef was so near, did not know much about it, thought he would finish washing down the decks, and then call the captain and all hands to tack ship. Called the captain who came on deck detween six and seven o'clock, and after damning the witness a little for letting the ship stand in so close to land, he ordered the ship to be put about. In attempting to tack, the ship misstayed, filled away again, and attempted to tack a second time, when she misstayed a second time, filled away again and found the bark to be inside the line of the reef. Thinks the bark misstayed on account of the lightness of the wind, it being about a three knot breeze; had misstayed before during the voyage; got on more sail and the breeze freshening the ship now went about. About this time several wreckers came aboard and remained a few minutes and left. The captain said after they had gone, that they wanted to pilot him, but he said he would have nothing to do with them, that he could pilot the vessel out the same way she came in. After making another tack the captain went aloft and directed a boy to hold the colours in the rigging as a signal for a pilot, but in a little while, said “No; he would not have a pilot, that he could see a channel out a little to the windward.” In answer to the signal one of the wreckers came on board, but the captain did not employ him. While on the outward tack and running about six or seven knots, the captain standing at the time on the house, the bark struck upon the point of a shoal and stopped, between eleven and twelve o'clock, having run some two feet out of water. John Taylor, one of the crew, says that the bark in the morning between six and seven o'clock misstayed two or three times. Robert Arnold, another of the crew, says she misstayed three times. Albury, one of the wreckers, says that he saw the bark in the morning outside of the reef about three miles to the leeward of the place where his vessel lay. Saw her misstay either two or three times and come inside of the reef. He ran down to him in company with other wreckers, went aboard and offered to pilot the bark out. The captain declined his offer, and he, and the other wreckers, left Afterwards saw a signal in the rigging and he boarded the bark a second time. The captain declined his services.

There is some conflict in the testimony in relation to the bearings of the ship, at the time she struck, and while she lay aground. Lieutenant Craven, of the United States steamer Corwin, first noticed the bark about eleven o'clock in the morning about six miles off to leeward, the steamer, at the time, running down inside, and thought, that the bark was close to the reef, but outside, but as he neared her, saw that she was inside. Was looking at her a little before, and as he thinks, at the time she struck. Thinks, that she struck in stays; head to wind or nearly so—(The witnesses all agree that the wind was N. E. or N. E. by E.) The Corwin passed close under the stern of the bark, and Mr. Craven thinks she headed nearly N. E. Lieut. Renshaw, of the Corwin, was looking at the bark at the time she struck; she was braced sharp up, but running. The pilot, Johnson, says she was running at the time she struck, he thinks, about five knots. The mate and three of the crew say, that she was running between six and seven knots, when she struck; she struck heavy, making her tremble. That she came a little, about a point, to the wind when she struck and remained stationary. The mate says, that after the bark was fast aground he looked at her compass and says that she headed nearly east. She was out of the water between two and three feet. Mr. Randolph of the revenue cutter service was at the bark between three and four o'clock. He says, that she was out of the water at the bows between two and three feet, that the wind was N. E. and that the wind struck the bark about a point on the weather bow, making her head, about N. E. by E. He says too, that his vessel rode head to wind and that he had in his mind's eye, at the time of giving his testimony, the relative position of the vessels, and that the bark and his vessel lay nearly parallel. The wreckers say that the bark headed while on the shoal E. quarter S. The testimony on this point is no further material than as aiding to determine the question, whether the master, seeing this shoal, before hand had luffed up, in order to put his bark on it, for, it extended only about ten or fifteen yards to leeward. I think the weight of the testimony is in favor of the idea, that the bark was running, at the time she struck, in a straight course, at the rate of about six or seven knots, and consequently, must have headed nearly east. The steamer Corwin passed close under the stern of the bark. Mr. Craven thinks she was afloat aft. He hailed the captain and offered his assistance to jerk the bark off. He received for answer from the captain “No; I will get off myself during the night.” He thinks the steamer could have hauled her off. He then sent Mr. Renshaw on board who offered the assistance of the steamer to jerk her off. The captain answered Mr. Renshaw, “No; I have run up two feet and I don't think you can do anything for me. I think I can get off myself.” He had been starting molasses casks on deck and Mr. Renshaw inferred from what the captain said and his staving the molasses, that he thought he would need to be lightened before she could be hauled off. Mr. Renshaw says the bark had run

959up at the bow two feet out of water. He thought at the time the steamer could pull the bark off. Mr. Randolph was at the bark about three hours later. He thinks the steamer could not have pulled her off, at the time he arrived, without lightening. After the captain had employed the wreckers to lighten and get the bark off, it does not appear, that he gave much attention to the matter, or exerted himself to save the property. On the contrary he seems to have left them to do as they please. This is a fact to be considered in connection with the others in deciding the question whether this bark was voluntarily stranded or not.

All the facts duly considered, I am of opinion, that they do not prove a voluntary stranding, and although it does appear, as will be seen more fully in a subsequent part of this opinion, that the captain failed very much in duty in not giving a better attention to the lightening and heaving the bark off by the wreckers, yet, this neglect of duty, taken in addition to the other facts, and circumstances already detailed, do not prove a voluntary stranding, nor make it probable, that he will not safely navigate his vessel to its port of destination if restored to him, nor bring the case within the rule of law, I have laid down. The bark and cargo will, therefore, be restored to him.

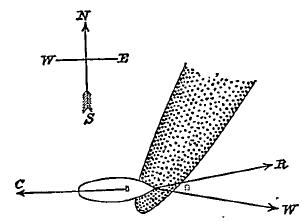

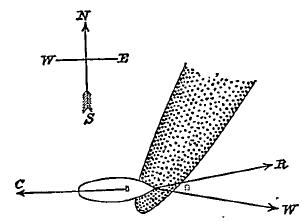

In relation to the question of salvage little need be said. The shoal on which the bark struck is called the “Triangle Shoal.” It could be seen from the decks of the vessel and is described by the witnesses as being about three hundred yards in circumference, and having from five to ten feet of water on it. It extended towards the northeast or the windward of the bark, about two hundred yards towards the southwest, it ran into a narrow point measuring about fifteen or twenty yards across directly ahead of the bark, and extended past the bows of the bark to the leeward about fifteen or twenty yards. The bark was aground on this point, heading, as the wreckers state, and as I think is true, east a quarter south. They carried out an anchor, according to their own account in an east by south direction and planted it in the greatest depth of water to be found, and as they say “in the only way in which the vessel could come off,” and then heaved taut. Mr. Albury, the principal wrecker, says, the anchor was carried out nearly ahead, but on the lee or starboard bow. This agrees with the libel. Taylor, a seaman belonging to the bark, says “the anchor led from the port bow over the chock about a point on the larboard bow. Peters, another seaman, says, the hawser went out over the larboard bow and led to the anchor planted off the larboard bow. Mr. Morris, the mate, says, that the hawser ran through the ship's chock on the larboard bow nearly ahead. Mr. Randolph says it ran about a point on the larboard bow. I think the anchor was planted nearly a point on the larboard bow. The diagram will show the position of the vessel and anchor.

R represents the anchor as testified to by Randolph, Taylor, and Peters. W, as alleged by the wreckers. Now, this bark ran ashore bow on, and the bow was two feet out of water. She was aground from the bow to aft the mainmast. Whether she was at any time aground abaft the mainmast is left in doubt by the conflicting testimony. Is there any possible room for doubt, as to what the effect of the anchor carried out by the wreckers and planted nearly ahead where they and the mate say it was, or at a point on the larboard bow, where Mr. Randolph, Taylor, and Peters say it was, must be upon the vessel, when heaved upon? It could have no other effect than to keep her on the reef, and heave her further on as she was lightened, and thereby prolong and increase the danger to the vessel. Accordingly the mate tells us, that after the wreckers had lightened the vessel and she began to lift, they heaved her ahead a little, perhaps half the ship's length, and then, eased away on the hawser, set the jib and foretopmast staysail and she went off sideways to leeward. The anchor ought to have been carried out astern, and this must have been so palpably clear to the wreckers at the time (for they say they could see the shoal) that there is no possible way of accounting for their carrying it out ahead, but by supposing that they desired to keep this vessel on the reef, and by lightening her to a considerable extent, and more than was necessary, make out an artificial and fabricated case, of meritorious salvage services, and impose it upon the court as genuine, with a view to a larger compensation than they thought the true state of the case would warrant! This conduct was a fraud, upon the owners of this property which they hoped so to conceal as to escape detection in this court. The master of the bark either connived at their conduct, or was grossly inattentive to, and neglectful of his duty. But, with his conduct, on this point, the court has nothing to do. Had then: conduct proceeded from ignorance or want of skill, they might be compensated, by a diminished rate of salvage, for the services really rendered. But their conduct cannot be accounted for on this ground.

Believing, therefore, as I am sorry to say,

960I do, that their design, in placing the anchor where they did, was such as I have mentioned, and dishonest and fraudulent, their entire salvage must he forfeited. The costs are in the discretion of the court. The wreckers have rendered real and valuable service, for I think the bark could not have been got off without their assistance, or a sacrifice of a considerable part of the cargo. The master, who represents the owners, has been at fault as well as they. These circumstances make it just, that the costs should be paid by the bark and cargo. It is therefore ordered, adjudged and decreed that the salvage of the libellants for their services rendered to the bark Byron and cargo while ashore on the Florida reef be forfeited, on account of their having carried out an anchor ahead of the bark, with a fraudulent view of holding her on the reef, until they had time to lighten her more than was necessary, and, in this manner fraudulently magnify their services into greater importance than they were entitled to, with a view to a larger compensation than the true situation of the vessel and their fair and necessary services would warrant, whereas, they ought to have carried the anchor out astern, as must have been evident, and plain to be seen by them, at the time. That the concurrence of the master in carrying it out ahead instead of astern is no justification of the wreckers, for their good conduct and good faith are due to the owners of the property as well as to the master. For this cause it is ordered that their salvage be forfeited and their libel be dismissed. That the costs and expenses of this suit be charged to the bark and cargo, and that after ascertaining the same and the charges incurred upon the property in this port, and the payment thereof, the marshal restore said bark and cargo to the master thereof, for and on account of whom it may concern.

1 The title of this case cited in blank cannot now be supplied.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.