Case No. 2,082.

BUCK et al. v. HERMANCE.

[1 Blatchf. 398; Merw. Pat. Inv. 414; 1 Fish. Pat. Rep. 251.]1

Circuit Court, N. D. New York.

June, 1849.

PATENTS—COOKING STOVES—COMBINATION—CONSTRUCTION OF CLAIM—INVENTION—VALIDITY—INFRINGEMENT—WHAT CONSTITUTES—DAMAGES.

1. Where, in a patent for a cooking-stove, the words of the claim were “the extending of the oven under the apron or open hearth of the stove, and in combination thereof with the flues constructed as above specified:” Held, that the claim was a combination of the extension of the oven under the hearth of the stove with the flues, as described.

2. Where, to a previously existing combination of an oven extending under the open hearth of a cooking-stove with reverberating flues, an inventor added a flue or fire-chamber in front: Held, that he had made a new and patentable combination.

3. A patent claiming the new combination was not void, as claiming the prior combination of the extended oven with the reverberating flues.

4. In a patent for a combination, where the novelty consists in the combination, it is immaterial whether the elements forming the combination are new or old.

5. In order to render a new combination patentable, the change from any former combination must be substantial, not formal, and must involve skill, ingenuity and mind. The new article must be different from the old one, not only in its mechanical contrivance and construction, but in its practical operation and effect in producing the useful result.

6. And the same test is a proper one in determining the question of an infringement on the patent.

7. The rule, on the question of damages for infringing a patent, is to give, not vindictive or exemplary damages, but the actual damages, which will be the ordinary profit derived by the patentee from the sale of the article containing the invention infringed upon.

[Cited in Perry v. Corning, Case No. 11,003; Mulford v. Pearce, Id. 9,908.]

[See Taylor v. Carpenter, Case No. 13,785; Hall v. Wiles, Id. 5,954; Pitts v. Hall, Id. 11,193; Parker v. Hulme, Id. 10,740; McCormick v. Seymour, Id. 8,726; Kneass v. Schuylkill Bank, Id. 7,875.]

At law. This was an action [by Darius Buck and others against John C. Hermance], tried before NELSON, Circuit Justice, and CONKLING, District Judge, for the infringement of letters patent [No. 1,157] granted to Darius Buck on the 20th of May, 1839, for certain improvements in the construction of stoves used for cooking.2 [Verdict for plaintiffs.]

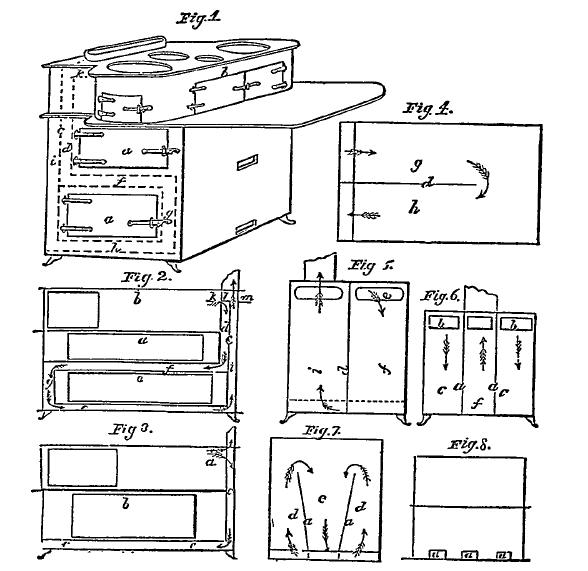

The invention of Buck consisted in taking the stove known as the Hathaway stove—in which the oven was extended under the apron or open hearth of the stove, and which had what are called reverberating flues, that is, two flues, starting from the top of the back of the stove, one at each side, running down the back and under the bottom to the front, and there uniting in a centre flue which returned under the bottom and up the back to the stove-pipe—and adding to it a close flue or fire-chamber in front, between the front plate of the stove and the front plate

551of the oven. Into this fire-chamber, which had no opening except into the flues under the bottom of the oven, the smoke and gases generated by combustion entered, and in it they circulated before returning through the centre flue. By this means, the front part of the oven was more effectually heated and a more uniform baking in all parts of it was ensured. In the Buck stove, the dividing strips between the side flues and centre flue under the bottom did not extend quite to the front plate of the stove. The defendant's stove had the extended oven and reverberating flues, and a hollow space between the front plate of the stove and the front plate of the oven, closed on all sides except where it communicated with the reverberating flues; but the dividing strips between the flues extended quite to the front plate of the stove, and upwards into the space in front. He insisted that the smoke and gases in his stove passed immediately from the side flues into and through the centre flue, without circulating in the fire-chamber, because there was no space for them to circulate; and that, therefore, he had no fire-chamber such as Buck had, but only reverberating flues. He therefore claimed that he did not infringe Buck's patent He also set up various stoves prior to Buck's as containing his invention, and produced evidence for the purpose of showing that Buck had fraudulently obtained a patent for the invention claimed, and that it was in fact the invention of one Solomon Crowell, Jr., from whom Buck obtained a knowledge of it

William H. Seward, Stephen A. Goodwin, Hooper C. Van Vorst, and Samuel Blatchford, for plaintiffs.

Samuel Stevens and David Buel, Jr., for defendant.3

[Darius Buck. Stove. Patented May 20, 1839. No. 1,157.]4

[J. G. Hathaway. Cooking-Stove. Patented Dec. 7, 1837. No. 505.]4

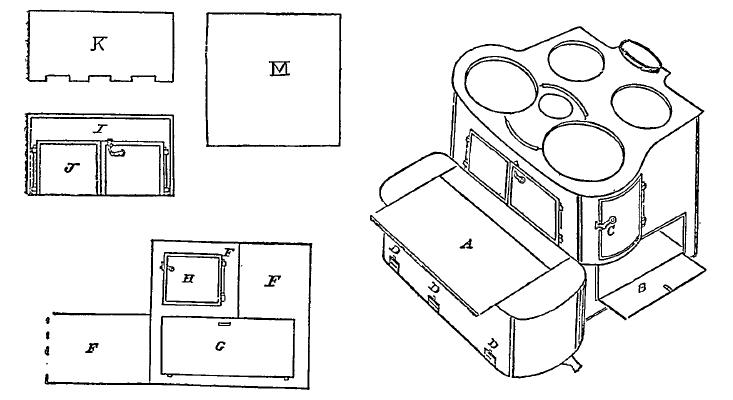

[Hathaway Cooking-Stove. Fig. 1 represents stove complete. The two lower apartments (marked in Fig. 2, a,) are ovens for roasting and baking. The upper apartment, b, Fig. 2, is the fire-room, the top of which is perforated with holes of any shape or size to admit of boilers; between the back of the stove and the backs of the fire-room and upper oven is a plate, c, running parallel with the back, which divides the space—which should be from two to six inches, according to the size of the stove—into two flues. This dividing plate rests on the back of the lower oven, which terminates the forward perpendicular flue, d, Fig. 2. The bottom of the upper oven and top of the lower one are placed at sufficient distance apart to form a horizontal flue, f, between the ovens, which is connected with flues which completely surround the lower oven. The front flue, g, is formed by a space between the lower front of the stove and the front of the oven. The bottom flue, h, is formed by a like space between the bottom of the stove and the oven bottom; the back flue, i, by a like space between the back of the stove and back of the lower oven, running to the pipe. The back of the fire-room—called the fire-plate—has an aperture, k, of sufficient capacity to admit of all the smoke to pass. The plate c, which forms a division of the upper flues, is made sufficiently wide to come as high as the top of the aperture in the fire-back, and on the top of said plate rests a plate or damper, 1, of sufficient dimensions to close either of the flues. This damper may be moved by a rod, m, which protrudes through a hole in the back of the stove, so as to cover either flue. When this damper is drawn so as to close the back flue, the smoke will pass through the aperture k in fire-back, and ascend immediately to the pipe, which is situated on the top of the stove, over the flues; when the damper is shoved so as to close the top of the front flue, the smoke and heat pass through the aperture k in the fire-back, thence down the back of the upper oven, through the horizontal flue between the ovens, down the front, and under the bottom, thence enters the back flue, and ascends to the pipe. When ovens have acquired a sufficient temperature of heat, the damper may be drawn to close the back flue, which stops the circulation of air and confines the heat in the flues around the oven, thereby keeping an even and proper heat for baking and roasting. The same principles may be applied to a stove with but one oven; which oven may be divided by horizontal and other plates into apartments, as represented in Figs. 3, 4, and 5.]4

In charging the jury, NELSON, Circuit Justice, remarked as follows:

The first thing which it is necessary to understand, and without a knowledge of which we can make no advance towards a proper settlement of the controversy between the parties, is the precise improvement which the patentee claims he has discovered. In other words, what has Buck invented in connection with the cooking-stove, as it existed before the date of his patent?

There is a radical difference of opinion on this branch of the case between the counsel who are engaged in the trial, and it is not at all surprising that there should be such difference, as the description given by the patentee is exceedingly obscure and difficult to comprehend. The question, however, is one of law, and one that the court is bound to determine, in order to give to the jury a guide by which to apply the facts in the case. The settlement of this question depends on a construction of the language of the patentee.

It will be seen, on reference to the specification, that the patentee describes particularly a cooking-stove, which, on the evidence in the case, there can be no doubt is what has been called throughout the trial the Hathaway stove. He specifies the flues of that stove, the two downward flues on the back at each corner, the side flues under the bottom to the front, and then the return flue through the centre. He describes also the flue or chamber in front of the stove, in connection with the side and centre flues; also the extension of the oven under the hearth; and then he undertakes to separate and distinguish from the general description which he has given of the Hathaway stove, the flues and the extended oven, &c., the part which he claims he has discovered, which was before unknown and not in public use. He names certain parts which he repudiates as not being within his invention, and then specifies the precise thing which he claims to have discovered and for which he applies for a patent.

The construction of the claim on which the court have agreed is this, that the invention of the patentee is a combination of the extension of the oven under the hearth of the stove, and the flues as described by him, with the flue or fire-chamber in front of the stove, formed by the two front plates. I am free to say that my own individual impressions are, that the patentee intended to claim the extended oven, and also a combination of the extended oven and the several flues he has particularly described, with the flue or chamber in front of the stove. But I have concurred with my learned associate in the construction which we have adopted for the purposes of this trial, with a view to enable the jury to reach the questions of fact involved in the case, intending, if the construction we have agreed on is erroneous, to give the defendant the benefit of the error.

The novelty, therefore, which is essential to sustain the patent, consists in the combination of which we have spoken. Our construction

554excludes the idea altogether, that Buck was the inventor of the extended oven. It excludes also the idea that he was the inventor of the several flues which he has described—the side flues, the return flue, and the flue in front. But, whether the extended oven or the flues which he has described are new or old, his claim is for the combination of the extended oven and the several flues with the flue or fire-chamber in front of the stove. Without going into the evidence, we may say in general terms, that the extended oven and the reverberating flues were before combined. That combination is found in the Hathaway stove, cast in Painesville, Ohio, as early as the fall of 1837, and again cast at Lockport, N. Y., in the spring of 1838; and, in the summer of 1838, a stove containing that combination was put up at Palmyra, N. Y., at a public house. We may say, therefore, that a combination of the extended oven with the reverberating flues, was discovered before the invention of Buck. We call your attention to this fact for the purpose of stripping the case of irrelevant matter.

The real point of novelty in the case, on the construction we have given to the patent and on the evidence is, if any, in bringing together, in connection with this previous combination of the extended oven and reverberating flues, the element of a flue or fire-chamber in front. The combination of the extended oven and reverberating flues, meaning the side flues and the centre flue, was old; but it is claimed on the part of the patentee, that he has brought into connection with this old combination, another element, the flue in front, making, as he claims, a new combination, of which he is the first discoverer and for which his patent has been issued. If that element was never before used in combination with the extended oven, and the patentee was the original inventor of it, then in our view it is a new combination, and, if useful, patentable. It is insisted on the part of the defendant, that the patentee, in respect to this combination, has claimed more than he invented; that he has claimed things which he did not invent, with those which he did; that the old cannot be separated from the new, where both are described in the patent; and that, therefore, the patent is void. The position taken by the defendant's counsel is this, that the combination of the side and centre flues with the extension of the oven was old, being found in the Hathaway stoves at Painesville, Lockport, and Palmyra, and that the patentee should not have claimed it in his patent; that he should have confined his claim to the combination of the fire-chamber with the extended oven; that then he would have set up a claim to the very thing which he insists he has discovered; that, as he has incorporated in his claim the combination of the extended oven with the reverberating flues, he has claimed too much; and that, therefore, the patent is void. We are inclined to think that this view is not well founded, and that, if the combination of the fire-chamber in front with the extended oven and flues is new, it is the subject of a patent. In a patent for a combination, where the novelty of the invention consists in the combination, it is altogether immaterial whether the elements forming the combination are new or old. All may be old; but, if they are brought together in a combination which was never before known and practically produces a new and useful result, it is a patentable subject. If then, looking at all the elements of which the combination consists, the bringing together of the extended oven, the side and centre flues, and the open chamber, for the purpose of improving the stove as it existed at the time, was new and produces a useful result, it is, as a whole, a new combination, and the proper subject of a patent.

Assuming, for the purposes of this trial, that this view of the claim is the sound one, the next question, and one of fact belonging to the jury to determine, is, whether or not Buck was the first and original inventor of this improvement. If he was, then, in the view we have taken, the patent is valid, and secures to him the exclusive right to the benefit of his improvement. If he was not, then the patent is void and no right can be set up under it.

It is insisted on the part of the defendant, that this combination was before known and in public use, and that Buck is not entitled to the merit of having first discovered it. On the part of the plaintiffs it is claimed that he was the first discoverer, and that, he is entitled to the enjoyment of the fruits of it. This question will depend, mainly, if not altogether, on a consideration of the stoves which have been produced in the course of the trial, and of which descriptions have been given by the witnesses on the part of the defendant, and of the testimony of the experts who have been examined. It is claimed by the defendant that the Hathaway stove with the double oven contained an open flue in front of the oven. In that stove, however, there were no reverberating flues. It is claimed, also, that the Burnell stove contained the combination; likewise the Stewart stove; and the Hoxie stove.

It is also insisted by the defendant that assuming the combination claimed by the patentee not to have existed in any stove in public use, still Buck was not the inventor of the combination, but that it belonged to Crowell. On the part of the plaintiffs it is insisted, that the Hathaway stove with the double oven, the Burnell stove, the Stewart stove, and the Hoxie stove, are altogether different in construction, combination, operation, and effect, from the stove or the improvement invented by the patentee. A specimen of each of these stoves, either a stove in use or a model not in dispute, has been

555exhibited in court. You have had an opportunity to examine them for yourselves. You have heard the testimony of the witnesses, and of the skilful experts, and, on this evidence and your examination, it is for you to determine, whether or not this combination of Buck's, as we have expounded it to you, was new or not. It is a question of fact which it is your province to examine and settle. There are some general principles, however, which may assist in guiding your deliberations on the evidence, to which we will briefly call your attention.

A formal difference between the combination of Buck and any previous combination is not patentable, and involves no skill, ingenuity, or mind. It is simply a difference in mechanical construction. In order to be patentable, the change must be substantial, as contradistinguished from formal. The new article must be different from the article on which it is claimed to be an improvement, not only in its mechanical contrivance and construction, but in its practical operation and effect in producing the useful result. Then it is not formal. Then it requires mind, ingenuity, labor, time, and expense. Keeping in view this distinction between a formal change and a substantial change, you will take up the evidence on both sides, the stoves claimed to contain the improvement, the witnesses, the experts, the explanations and arguments of counsel, and it will be for you to determine whether the combination claimed to have been invented by the patentee was new, or whether it existed before. If it was new and is useful, then it is a patentable subject, and the patent is valid. If it was not new, but old, then the patent is void.

If you shall come to the conclusion that the patent is valid, as embracing a new combination, then the next question will be, whether or not the defendant has appropriated the combination of the patentee to his own use in the manufacture of his stoves. Two of the defendant's stoves have been produced in court one is produced by himself, and is conceded to have been manufactured by him. You have had an opportunity to examine it in connection with the Buck stove. The same doctrine that we laid down on the first question of fact, in respect to distinguishing the combination of Buck from any previous combination, is equally applicable to this branch of the case. A formal change on the part of the defendant will not distinguish his stove from the Buck stove. That would be an evasion. The change must be substantial. It must be a difference in the mechanical structure, in the physical existence of the thing, and also in its practical operation and effect in producing the result; and it will be for you, on examining the construction of the two stoves, and the testimony of the experts and the other witnesses, to determine whether the stove of the defendant embraces the combination of the patentee or not. If it does, then it is made in violation of the patent. If it does not, then it is no violation, and the defendant is entitled to your verdict.

If you should come to the conclusion that the patent is valid, and that the defendant is guilty of violating it, the next question will be as to the amount of damages. On this branch of the case there is no contradiction. It is admitted by the defendant that he has manufactured one hundred of his stoves. It appears that the profits derived from the manufacture of the Buck stove are two dollars or two dollars and a half for each stove. The rule which is to govern on the question of damages is, to give the actual damages; not vindictive or exemplary damages, but the actual loss sustained, which will be the ordinary profits the patentee derives from the sale of his stoves. It will be for you, on the evidence in the case, to say what shall be the amount of the recovery.

The jury found a verdict of $200 for the plaintiffs.

[NOTE. For other cases involving this patent, see Buck v. Gill, Case No. 2,080.]

1 [Reported by Samuel Blatchford, Esq., and William Hubbell Fisher, Esq., and here com piled and reprinted by permission. Merw. Pat. Inv. 414, contains only a partial report.]

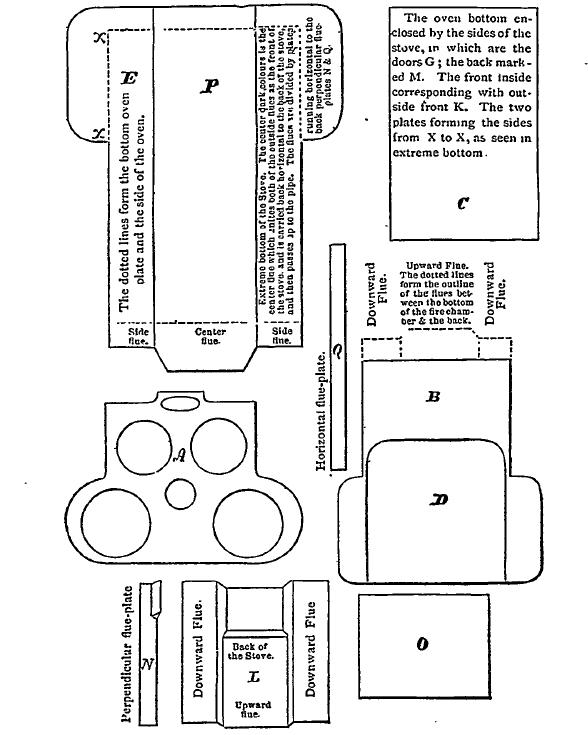

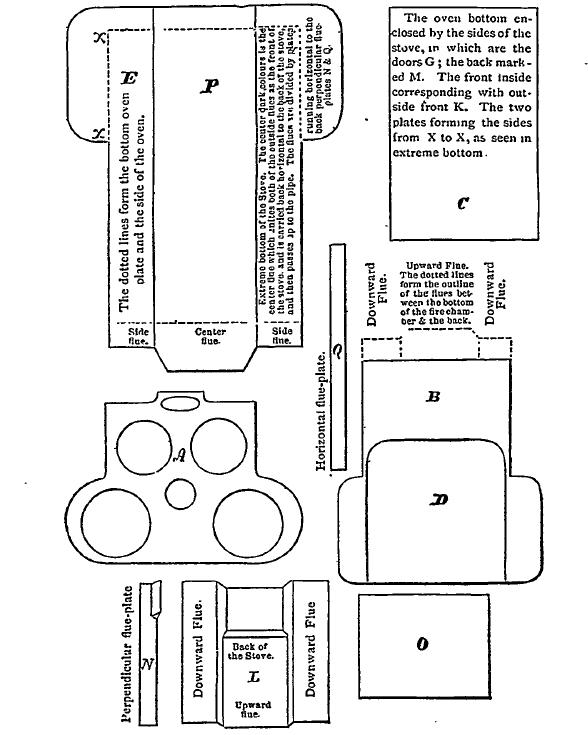

2 The specification annexed to the patent was in these words: “Whereas difficulties occur in the cook-stoves now in use, in carrying on at the same time baking and boiling, and also in having an oven of such uniform temperature that every part will cook or bake uniform; and also in having an oven of sufficient size so as to do away with the occasional use of the brick oven, even in large families, without any increase of fuel; and also in having an oven around which there is a certain free and uniform draft. And whereas my invention has respect to the afore said difficulties: Now therefore he it known, that I, Darius Buck, of the city and county of Albany, and state of New-York, have invented certain improvements in the construction of stoves used for cooking; and I do hereby declare, that the following is a full and exact description thereof, reference being had to the drawings which accompany this specification, and are a part of the same: I build my stove as follows: Plate marked E P E, I lay down first, and call it my extreme bottom; I divide plate E P E, into three flues, two of which are on the outside of the sunk-bottom part of the plate, and are used for passing the smoke and heat forward under the oven. The other flue, marked P, I use as the return flue of the smoke and heat under the oven. These flues are constructed by two pieces similar to the piece marked Q, being cast on the bottom; I then set up the plate L, which is the back of the stove; then the plates marked F F F, which are the sides; I then put in the plate C, which is the oven bottom, which rests on plates Q Q; I then put in the plate M, which is the back and front oven plate; I then put in plate K, which is the front of the stove under the hearth; I then pass two plates similar to plate N down along plate L till they reach plate E P E, by which means I get my two downward flues S S; I then put in my plate B D; I then put in my plate I J; I then put on the top plate A, which completes the stove. I thus place my oven M M in drawing No. 1, in such manner that the fire is made on plate B, drawing No. 2, which is the fire bottom and top plate of the oven and hearth; then the fire passes along plate B down plate L, in the downward flues marked S S in drawing No. 2; thence along plate E E in drawing No. 2; then back through flue P in drawing No. 2; then up the upward flue in plate L, drawing No. 2, to the outlet R in plate A, drawing No. 2; the oven is thus made to extend from the back part of the stove to the front of the stove under the open hearth, so that the back plate of the stove is a flue plate; as is also the front plate under the open hearth of the stove. The plates that form the outside of the flues around the oven under the hearth are so constructed, that any horizontal division of the flues and oven under the hearth is similar to the hearth, or the last mentioned outside flue plate may be made straight or flaring; but they are better to curve according to the shape of the hearth plate, for by preserving this form, the flue will be enlarged; the heat of the hearth, the top of the oven, the temperature of the oven, and the draft, all will be increased. I do not claim as my invention the placing of the oven in cooking-stoves under the fire place of the stove, as that has been long known and in use, nor do I claim the invention of reverberating flues for conducting the heat, &c., under the oven, as they have also been for a long time known. What I do claim as my invention, and for which I desire to secure letters patent, is the extending of the oven under the apron or open hearth of the stove, and in combination thereof with the flues constructed as above specified, by which means I am enabled to obtain greater room for baking and other cooking purposes, and effect a greater saving of expense and fuel than in cooking-stoves of the ordinary construction.”

3 This case was tried four times. On each of the first two trials the jury disagreed. On the third trial the defendant had a verdict, but a new trial was granted. See 1 Blatchf. 322 [Case No. 2,081].

4 [From 1 Fish. Pat. Rep. 251.]

4 [From 1 Fish. Pat. Rep. 251.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.