Case No. 1,946.

4FED.CAS.—17

BROOKS et al. v. BICKNELL et al.

[4 McLean, 70;1 3 West. Law J. 109; 1 Fish. Pat. Rep. 72.]

Circuit Court, D. Ohio.

July Term, 1845.

NEW TRIAL.—OBJECTIONS TO VERDICT—WEIGHT OF EVIDENCE—EQUITY—DIRECTING ISSUE AT LAW—PATENTS—INFRINGEMENT—WHAT CONSTITUTES—INJUNCTION.

1. A verdict on an issue at law, directed by a court of chancery, will not be set aside on the ground that it is against the weight of evidence, unless the preponderance of the evidence shall be clear. Such an issue is not directed as a matter of form.

2. Where doubts exist, or testimony conflicts, or where the subject matter is fit to be examined by a jury, an issue should be directed. Patent right cases are of this character, as they are to be decided by experts, who generally differ in opinion.

[See Goodyear v. Day, Case No. 5,569; Van Hook v. Pendleton, Id. 16,851; Foote v. Silsby, Id. 4,918; Parker v. Hatfield, Id. 10,736.]

3. There is no infringement of a combined machine, unless all the parts which constitute the combination, are used.

[Cited in Crompton v. Belknap Mills, Case No. 3,406.]

4. Before the right under a patent is established at law, chancery will not decree an injunction, unless such right shall be clearly established.

[In equity. Bill by Moses Brooks and Joseph L. Morris against Benjamin Bicknell and Ebenezer Jenkins to enjoin infringement of a patent for an improvement in wood working machines, granted to William Woodworth December 27, 1828, and extended to his administrator February 16, 1842. On the question of validity of the patent and renewal, the court directed the issue to be tried before a jury (see Brooks v. Jenkins, Case No. 1,953), and the jury found for defendants. Defendants now move to set aside that verdict, and for a new trial. Denied.]

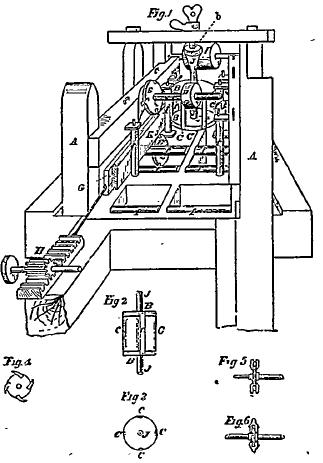

[William Woodworth, Planing Machine. Patented Dec. 27, 1828. Extended Dec. 27, 1843, and Dec. 27, 1849. Reissued July 8, 1845.2

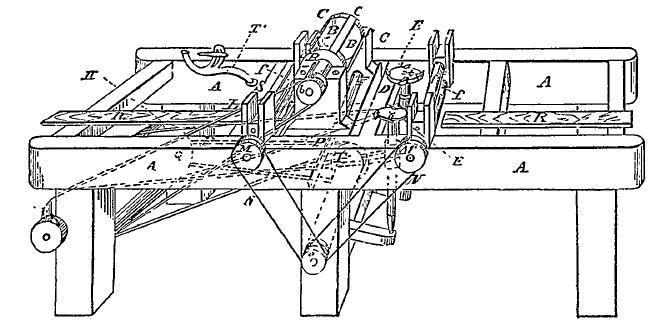

[Planing Machine. Fig. 1 is a perspective representation of the principal operating parts of the machine. A A is the frame of the machine; it may be either of wood or iron, and vary in size according to the work to be done. B B, heads of the planing cylinder; and C C, the knives or cutter which extend from one to the other of said heads, to the peripheries of which they are attached by screws. The knives, C C, may be placed in a line with the axes, J, of the cylinder, or obliquely thereto, as may be preferred: in the latter case the edge should form the segment of a helix, b represents a pulley near the upper end of the axes J. I represents a pulley or drum made to revolve by horse, steam, or other motive power, from which a belt may extend around the pulley b, to drive the planing cylinder and other parts of the machinery. G is the carriage, represented as being driven forward by means of a rack and pinion, H; against this carriage the plank K, which is to be planed, tongued, and grooved, is placed and made to advance with it.

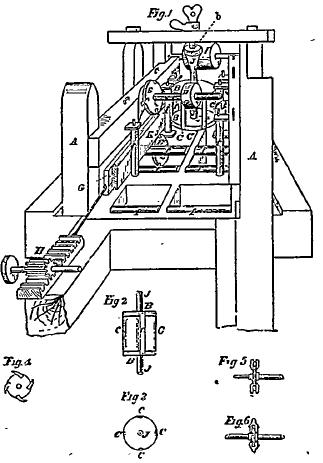

[Fig. 2 is separate view of the planing cylinder with its knives or cutters, and Fig. 3 an end view of one of the heads. E E are the revolving cutters or tonguing and grooving wheels; and D D, wheels upon their shafts which may be driven by bands or otherwise, in order that said wheels may revolve in the proper direction. Fig. 4 is a side view of one of these wheels; Fig. 5 is an edge view of the tonguing wheel, and Fig. 6 is an edge view of the grooving wheel—the latter being each shown with two cutters in place.]

Wright, Coffin & Miner, for plaintiffs.

Walker, Galloway & Kebler, for defendants.

MCLEAN, Circuit Justice. This is a motion for a new trial of an issue at law, directed by the chancery side of this court. The complainants filed their bill, representing that they are the assignees of Wood-worth's planing machine, etc., for the county of Hamilton and other territory; that the defendants have infringed their rights by the use of a machine, the same in principle as Woodworth's; and they pray that the defendants may be enjoined from the use of their machine. The court directed an issue at law to try the rights of the respective parties. An issue was made up, involving the following points in regard to the validity of Woodworth's patent: 1. The renewal of the patent by the administrator of Woodworth. 2. The assignment of the patent to the plaintiffs. 3. The sufficiency of the specifications. 4. The validity of the disclaimer of the circular saws by the administrator. 5. The novelty of the invention. 6. Whether the machines are substantially the same in principle.

More than thirty witnesses were examined in the case, either orally or by written depositions, many of them being eminent for their theoretical and practical knowledge in mechanics, and in the structure of machinery in general. On all the facts submitted to the jury, the witnesses differed in opinion, rather more than half being on the side of the plaintiffs, and the others for the defendants. The cause was patiently heard by the jury, argued by counsel, and submitted to them by the court They returned a general.

[Wm. Woodworth, Planing Machine. Patented Dec. 27, 1828. Extended Dec. 27, 1842, and 1849. Reissued July 8, 1845.]2

verdict for the defendants. And now a motion is made to set aside the verdict. In Stace v. Mabbot, 2 Ves. Sr. 552, it is said that “courts of equity are much less strict in granting new trials than courts of law, it being necessary, not that the question should be decided to the satisfaction of others, though ever so often, but that the conscience of the court should be quite satisfied.” In another case it was said, “the court will not direct a new trial of the issue, if application for a new trial rested solely upon the ground that the verdict was against the weight of evidence.” In this case, there is no objection, founded on the admission or rejection of testimony—none to the conduct of the jury, or the charge of the court. The motion for a new trial rests wholly on the allegation that the verdict was against the weight of evidence. In an ordinary case at law, a new trial is rarely, if ever, granted on this ground. The jury weigh the evidence, and determine on the credibility of witnesses; and when they have thus determined, the preponderance must be striking and clear, to authorize a court to order a new trial. The conscience of a chancellor must, it is said, be satisfied: but the same may be said in a court of law. The word, conscience, here means nothing more than a sacred and legal conviction in the mind of the court, that the verdict is sustained by the evidence.

The finding of a jury is entitled to great weight, whether on an issue directed out of chancery, or in an ordinary case at law. If this were not so, why should a court of chancery direct an issue? This is not done as a mere form, but to relieve the court in a matter of doubt, or because, from the nature of the case, and the conflict of the testimony, it is fit that a jury should decide. Of this character was the case under consideration. It involved the structure of complicated machinery, the sufficiency of its description, and its identity in principle with other machines. These points could only be satisfactorily decided by the testimony of experts; and, as usual in such cases, there was great diversity of opinion among the machinists examined as witnesses. Now, such a controversy is not to be determined alone by the number of witnesses on the respective sides; but their character, knowledge, experience, and manner of statement, have great influence in the decision. Such a matter is most appropriately referred to a jury. The rule has been well settled, that in these cases an injunction will not be decreed, unless the right is clear, or has been established by an action at law. That these same issues were submitted to a prior jury, which, after a full hearing of the evidence, were discharged by the court, because they could not agree upon a verdict, is a fact which can not be entirely overlooked on this motion. As the verdict was a general one, the court can not judicially know on what point or points it turned. If the jury found against the plaintiffs on the third, fourth, fifth, or sixth point above stated, unless otherwise instructed, their verdict would have been, generally, as rendered, for the defendants. In this aspect of the case I have had the most difficulty. For if the jury found that the defendants' machine was an improvement upon the plaintiffs', there was still an infringement, if the plaintiffs' entire machine had been used by the defendants. I say the plaintiffs' entire machine, as it was the opinion of the court that Woodworth's specifications could only be sustained for a combination of known mechanical powers. Had Woodworth's machine, as specified, been an improvement upon any other, then the use of any part of the improved machine would be an infringement. But there is no infringement of a combined machine, unless every part be used. All the witnesses called by the defendants, stated their planing irons were substantially different in their mode of being fastened and operating, from those of the plaintiffs; and Keller, one of the principal witnesses of the plaintiffs, coincided with this view, and said he considered that in this respect the defendants' machine was an improvement upon the plaintiffs', which entitled them to a patent. Now, if this improvement was substantially different from one of the combined parts of Woodworth's machine, though it was substituted for it, and all the other parts were used, still there was no violation of the plaintiffs' right. The same parts must be used in the same combination, to make the defendants liable. This I understand to be the rule as laid down in numerous cases.

Upon the whole, on a full consideration of the case as stated, and as shown by the evidence, I do not feel authorized to grant a new trial, or set aside the verdict. There is evidence, and strong evidence, to sustain the finding of the jury. On the other side, the evidence for the plaintiffs is as strong, perhaps stronger; but the preponderance is not so clear as to enable the court to disregard the verdict. If Woodworth's specifications had been sufficient for an improved machine, and the same points had been submitted to the jury, that were submitted to them in this case, I should have ordered a new trial.

[NOTE. For conditional dissolution of interlocutory injunction. See Case No. 1,944, and for an opinion given in the progress of the suit, as to whether or not the benefit of the renewal issued to the assignee of the original patent, see Id. 1,945. For other cases involving this patent, See note to Bicknell v. Todd, Id. 1,389.]

1 [Reported by Hon. John McLean, Circuit Justice.]

2 [Cut from 1 Fish. Pat Rep. 72.]

2 [This cut and the description of same were taken from the case as reported in 1 Fish. Pat. Rep. 72.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.