771

Case No. 1,583.

BLYDENBURGH et al. v. WELSH.

[Baldw. 331.]1

Circuit Court, D. Pennsylvania.

April Term, 1831.

SALE—CONDITION'S—FRAUD—WAIVER—TIME OF DELIVERY—DEMAND—REFUSAL—MEASURE OF DAMAGES—VARYING PRICE.

1. On the 7th of April, A sold B a quantity of coffee “provided it is not sold in New York:” Held, that the sale to B. was absolute, if the coffee had not then been sold; the proviso does not refer to a future sale.

2. A purchaser of goods is not bound to answer the inquiries of a seller respecting the state of the market.

3. If after a party has acquired a knowledge of facts tending to affect a contract with fraud, he offers to perform it on a condition which he has no right to exact, he thereby waives the fraud and cannot set it up in an action on the contract.

4. What is fraud in a purchaser of an article of merchandize, considered.

5. Where no time is fixed for delivery of goods sold, the law makes them deliverable in a reasonable time: if when a demand is made there is no objection made as to time, or it was not then made a question by the vendor, the contract will be deemed to be broken by a refusal.

6. The rule of damages is the market price of the goods at the time when they were deliverable, a jury cannot give damages beyond the market value, though the refusal to deliver may have been with a view to profit. But if the price was not fixed and appears by the evidence to have ranged between different rates, the jury may take the highest, lowest or medium rate, according to the conduct of the defendant.

This was an action [by Blydenburgh and Burns] to recover damages from the defendant, for not delivering a quantity of coffee agreeably to a contract between him and the plaintiffs, through the agency of Joshua Percival, a regular broker employed by the plaintiffs.

The contract was as follows:

“Sold Mr. Percival all the coffee purchased from Mr. Jacobs, said to be about two hundred and eight thousand pounds at 17¾ cents, at four months, or two per cent, off, provided it is not sold at New York. J. Welsh.”

“7th of April, 1825—about eight o'clock, a. m., or between eight and nine o'clock. J Percival.”

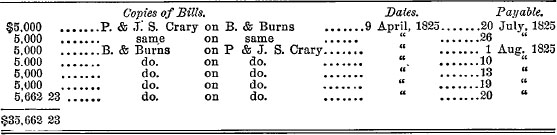

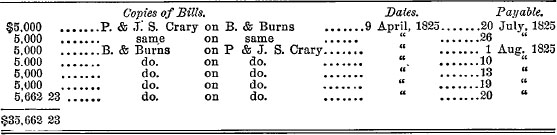

The quantity of coffee was two hundred thousand nine hundred and fourteen pounds, the price at 17¾ cents, was 35,662 dollars 23 cents. Policy of insurance, at Boston, 8th of April, 1825, by B. & B., 41,000 dollars (exact amount being unknown).

The following letters and papers were read by the plaintiffs:

“Philadelphia, 13th of April, 1825. Sir,—Circumstances connected with the purchase of coffee, which you made of me in the morning of the 7th instant, came to my knowledge yesterday, which will, in my opinion, annul the contract; but in order to avoid inconvenience, I will give the bill of parcels, and deliver the coffee, if your employer, Mr. Blydenburgh, is prepared to make the payment, (yesterday he had not the acceptances) on condition that an amicable action is entered in the circuit court of the United States to try the question, and if the contract is unlawful, to assess the damages I have sustained. Also, on condition that I am protected from the claim of William Read for Le Roy, Bayard & Co., if any should be made. Yours, respectfully, J. Welsh. To J. Percival.”

“Philadelphia, 23d of April, 1825. To Blydenburgh & Burns, New York. Mr. Read informs me that he is not authorized to give up the claim of Le Roy, Bayard & Co. to the coffee, and renews the proposal he made (which you rejected), of submitting it to friends. On receiving a protection from you against this claim, either the paper handed you for signature the 12th of April, or any other, I will deliver you the coffee, which remains where it was stored the 7th and 8th instants. I will say a word about this transaction more than that I want the funds, and feel a sincere desire to end the unpleasant controversy. Should you decline, I intend to ship the coffee, having a vessel ready, or dispose of it Yours, respectfully, J. Welsh.”

Paper handed Mr. B. for signature:

“Should any expense or damages arise from a claim for the purchase or supposed purchase or sale of coffee in New York, belonging to John Welsh, and which we purchased on condition it was not sold in New York, we hereby promise to pay all expense or damage, and clear the said Welsh of all liability.”

“It is admitted by the defendant, that on the 14th of April, 1825, the plaintiff, Blydenburgh, called on the defendant at his couning-house, and in the presence of a witness, told the defendant that he was prepared to pay him the exact amount of the coffee, in acceptances of Messrs. P. & J. S. Crary of New York, of bills drawn by Blydenburgh & Burns, and acceptances of Blydenburgh & Burns of bills drawn by P. & J. S. Crary; that the defendant said he would not deliver the coffee unless Mr. Blydenburgh complied with the terms specified in a note of the defendant to Joshua Percival; that Blydenburgh then tendered to the defendant seven bills accepted and drawn as above stated, true copies of which are hereto

772

annexed; that the defendant took the bills in his hand, looked over them; said he was perfectly satisfied with the paper, and would rather have it than the money, which Mr. Blydenburgh told him, if he preferred, he might have, and then returned them to Mr. Blydenburgh, saying, he would not deliver the coffee except on the terms before specified. Mr. Blydenburgh then told him he should be under the disagreeable necessity of commencing an action against him. Rich. Peters, for defendant.”

Indorsement on above. “I agree that the within shall be read in evidence on the trial of the cause. Richard Peters, defendant's attorney. October 5th, 1830.”

All dated New York.

It appeared in evidence, that Mr. “Welsh had made an offer of the same lot of coffee to Mr. Read of this place, agent of Le Roy & Bayard of Mew York, at 17¾ cents, at four months, and to deliver it at Hamburg or Petersburg at a certain freight Mr. Read wrote to Le Roy & Bayard on the 6th of April, 1825, informing them of the offer, to which they replied on the 7th, stating, that they never purchased, unless the debenture was taken in payment On the 8th Mr. Read offered to take the coffee at short price, the debentures to be in part payment, to which Mr. Welsh replied, that if his offer had been unconditional at short price, he would have considered it a sale to Le Roy & Bayard, but as they had not accepted his offer, it was no sale to them; he had sold it to another person, and it was now too late to sell to them. Mr. Read believed he had no right to the coffee, so informed Le Roy & Bayard, and they never sought to enforce the offer, but there was no evidence that such belief was communicated to Mr. Welsh. Coffee took a rise on the 7th of April, which continued for some time, the price ranging from 18 to 21 cents. Mr. Welsh retained the coffee till the 10th of May, when he shipped it on his own account, invoiced at 19¾ cents. It was alleged on the part of Mr. Welsh, that the state of the market for coffee was known to Mr. Percival on the 7th of April, but was concealed from Welsh and misrepresented; this was denied on the other side, and much testimony taken respecting it, which it is not necessary to refer to; in substance, it was, that on the arrival of the ship Crisis at New York, the accounts from Europe relating to the cotton market caused a rise in that article, but no notice was taken of coffee; on the morning of the 7th of April plaintiff, Blydenburgh, came express from New York, in advance of the mail, and gave orders to Mr. Percival to purchase this lot of coffee from defendant, which he had offered the day before but which Mr. Percival had declined. The arrival of the Crisis, and the rise of cotton, was entered on the coffee-house books before this sale was made, and was known to defendant; the rise in coffee took place on account of sales made on that day, and speculations in anticipation of its rise. The avowed object of the expresses was to purchase cotton; the purchases of coffee were more active, in consequence of calculations on its probable demand, and not from any definite information. At the time of the purchase Mr. Welsh asked Mr. Percival if there was anything about coffee, to which he replied, nothing on the books of the coffeehouse except the rise of cotton.

Mr. Chauneey and Mr. Sergeant, for the plaintiff.

By the terms of the memorandum of the 7th of April, the sale to the plaintiff was absolute; if Le Roy & Bayard did not accept the offer previously made, defendant was not at liberty to make a new one, or to vary the terms proposed. The offer was not accepted, and both defendant and Mr. Read considered it as no sale; it was therefore not sold in New York on the 7th. Mr. Welsh has no right to claim any indemnity, when he could in no event be subjected to any injury. As no time was fixed for the delivery of the coffee, the law makes it deliverable in a reasonable time, which, in this case, may be taken to be the 14th of April, when the coffee was demanded, and the defendant made no objections to the time, but offered to deliver it if the indemnity he required was given.

The contract was broken on that day by the refusal to deliver, in consequence of which we have a right to recover the difference between the price at which the coffee was sold on the 7th, and the price at which it could have been purchased on the 14th, with interest from that day. The price was then 20 cents, at less than which the plaintiff could not have purchased. This is the true rule of damages, which puts him in the same situation as if the contract had been complied with. [Shepherd v. Hampton] 3 Wheat. [16 U. S.] 204; [Hopkins v. Lee] 6 Wheat. [19 U. S.] 118; 2 Conn. 487; 5 Conn. 222.

773

The contract was fair; Mr. Pereival was not bound to communicate his instructions from the plaintiff, nor were either hound to disclose any knowledge they had of circumstances which might affect the market; they did or said nothing tending to impose on the defendant by any falsehood or misrepresentation, and had a perfect right to take advantage of the rise in the market, if they practised no deception on the defendant The case of Laidlaw v. Organ is decisive of this point (2 Wheat. [15 U. S.] 178, 195); the silence of a party is not imputable as fraud, unless there is an obligation to disclose (2 Brown Ch. 420; 10 Ves. 470; 7 Johns. Ch. 201); there must be fraudulent concealment or misrepresentation to taint the contract with fraud (18 Johns. 403).

Mr. Peters and Mr. Binney, for defendants, admitted the rule of law to be as laid down in [Laidlaw v. Organ] 2 Wheat. [15 U. S.] 195, in relation to the communication of the vendee's information to the vendor of goods. In contracts of insurance, the insured must communicate his whole knowledge of every matter material to the risk, but this is not required in other contracts. In contracts of sale the true question is, whether what is said, or omitted to be said, tends to deceive. The party may be silent when asked, for his silence puts the other on his guard, a contract may be avoided though there is no design to mislead or deceive, if what the party say, is calculated to have that effect. An answer may be true, but by reference to the subject matter may tend to deceive; there may be partial truth yet general falsehood; on this subject the same rule prevails as in contracts of insurance; the assertion of a fact includes all natural inferences (Phil. Ins. 82); if the vendor throws himself on the confidence of the vendee, and he either says what is not true, or does not say what is true, it is a fraud in law (2 Dow, 263, 266; [Laidlaw v. Organ] 2 Wheat [15 U. S.] 186, 190, note); or has knowledge of any fact not disclosed, which is contrary to his representation (10 Ves. 470). The rule of damages for not delivering articles sold, is not what the vendor could purchase the article for, but the injury sustained; the vendee is entitled only to indemnity, that is, to be put on the same footing, as if the article had been delivered. As a general rule, the price demanded is the market value, for the purchaser must pay it; but if the market is stagnant, if none or but small sales are made, the true rule is, what could the article sold have been sold for, if the plaintiff had had it in his possession, in the state of the market on the 14th of April when it was demanded? The jury must look to what a sale would have produced, and not the price demanded by holders at a time when prices were nominal.

BALDWIN, Circuit Justice, charged the jury as follows:

The contract of sale on the 7th of April was conditional, “provided it is not sold at New York;” as the contract is in writing its meaning is matter of law to be settled by the court In our opinion, it does not refer to a sale to be made in New York after the 7th, but to a sale then made; the proviso is not prospective, so as to bring a future sale within the condition; if it was not sold before the contract was signed, the sale to the plaintiffs was absolute. On the other hand, if the offer made on the 6th had been accepted by Le Eoy & Bayard on the 7th, the coffee would have been in law and fact sold on the 6th, and the plaintiffs would have had no right to it But to make out a sale on the 6th, the precise offer made by Mr. Welsh must have been accepted; any variance in the terms would have been a new contract which he was not at liberty to make. The letter of Le Eoy & Bayard of the 7th was not such an acceptance, and was so considered by Mr. Welsh and Mr. Eead; nor do Le Eoy & Bayard even seem to have made or contemplated any demand on Mr. Welsh. The contract thus becomes divested of the only condition annexed to it, without any right in Mr. Welsh to require any indemnity against Le Eoy & Bayard. It bound Mr. Welsh to deliver the' coffee, if it is not infected with fraud in the suppression of truth, or the suggestion of falsehood. On this subject the law is well settled.

To avoid a contract on this ground of fraud, there must be a concealment of something, which the purchaser is bound to communicate to the seller, or some misrepresentation on a matter material to the contract, which misleads and deceives him, or is calculated to do so. But a purchaser may avail himself of information which affects the price of the article, though it is not known to the seller; though the latter inquires if there is any news which affects the price, the purchaser is not bound to answer, and the contract is binding, though there was news then in the place which raised the price thirty or fifty per cent [Laidlaw v. Organ] 2 Wheat [15 U. S.] 195.

When the means of acquiring knowledge are equal to both parties, he who first receives it may avail himself of his activity or of accident; but if he makes use of any circumvention or art to conceal the fact from the other party, it will invalidate the contract The buying and selling merchandize being for mutual profit, the law exacts only good faith; one is not bound to impart to another his views of speculation, his opinion of the effect of news or events, the bearing of the rise of one article on another, or the results of his mercantile skill and knowledge of the markets, fairly acquired, and not unfairly concealed. An unfair concealment is where pains or means are taken to keep the other party in ignorance of material facts, when he asserts a fact not true, or true to the letter but not the sense—not

774

according to the common meaning and acceptation of the words used, and calculated to impose upon or deceive—representing a fact to be one way, but concealing circumstances which bore directly upon it in a contrary way; in a word, any declaration which induces another to buy or sell, on the confidence in its truth, according to the common acceptation of the words used in reference to the transaction, is fraudulent suppression, if the assertion is not strictly true as so understood, though it may be true in another sense different from the ordinary import.

Misrepresentation is asserting what is not true in whole or in part; though not bound to answer a question, yet if the party does answer he must do it fully, fairly and in good faith, so as to give the other the benefit of the question and the information sought: if a representation is voluntarily made without being requested, it must be substantially true in every matter material to the contract. As every contract is presumed to be affected by the state of things as represented, any substantial change will vacate it, because not made according to the meaning and intention of the parties; so where confidence is reposed and abused by unfair concealment. In either case it matters not whether there was a fraudulent intention. If the party is in fact deceived or induced by the conduct or declaration of the other to enter into a contract which he would not have made had he known the true state of things, it cannot be enforced. In applying these rules to this case you will inquire whether the agent of the plaintiff said or did anything tending to impose on the defendant, from which you can infer an imposition by the buyer upon the seller, according to the principles of fair dealing as understood between merchant and merchant.

Mr. Percival was not bound to communicate his instructions to purchase, or his opinion of the effect of the rise of cotton on the price of coffee, nor the state of the market as to the sales of coffee then going on, if Mr. Welsh's means of information were the same as his. You will judge from the evidence whether there was any concealment of any other fact material to the sale which ought to have been disclosed, or any untrue representation made in the conversations between the parties. In deciding on this part of the case you will also inquire whether the defendant, on the 13th of April, was ignorant of any facts which had a material bearing on the fairness of the contract; for on that day he made a written offer to deliver the coffee if the plaintiff would sign the paper of indemnity. This is a waiver of the objection to the contract on the ground of fraud, if he was informed of all matters which bore upon that question; if he remained ignorant of them then it is no waiver.

Should you think the contract fraudulent in law or fact you will find for the defendant; if you think it fair, then the only question will be the amount of damages, as it is clear that there has been a breach by the defendant No time being fixed for the delivery of the coffee, the law makes it deliverable in a reasonable time, which depends on circumstances; as no objection was made in point of time, when a demand was made by the plaintiffs on the 14th of April, and nothing appears in the evidence to show that time ever was or ought to have been made a question between the parties, you may assume that as the time of delivery, and by the refusal of the defendant, that the contract was then broken. The rule of law, as to the measure of damages to which the plaintiff is entitled, is the market price or true value of the coffee in the market on the 14th of April, taking all circumstances into view; you will not confine your inquiry to the price at which the plaintiff could have sold it, if it had been delivered according to contract, or what he must have paid, if he had purchased on that day; but taking these and all other circumstances together, as bearing on the value of the coffee, as an article of merchandize in the hands of the plaintiff, for the purpose of taking the advantage of the market, decide from the evidence what it was then worth, not its intrinsic but its market value.

The plaintiff must be put in as good a situation as if the coffee had been delivered; he must have a just indemnity for the breach of the contract, but you cannot go beyond the value of the coffee at the time of delivery, whatever opinion you may have of the reasons or conduct of the defendant for not making it. If you are satisfied from the evidence that there was on that day a fixed price in the market, you must be governed by it; if the evidence is doubtful as to the price, and witnesses vary in their statements, you may adopt that which you think best accords with the proofs in the case. You must take what you believe the market price or value, but may take the range of the market as proved by the witnesses, fixing on the highest, lowest, or medium rate, at your discretion. We think the rule applicable to contracts to deliver stocks a correct one in cases of this kind, by keeping within the range of the market on the day of delivery, to fix on the higher, lower or medium value, as the breach of the contract may have been wilful or innocent in your opinion. The plaintiff is entitled to your verdict for such value, with interest from the day of delivery.

The jury found for the plaintiff, whereupon the defendant's counsel moved for a new trial; 1, for excessive damages; 2, for misdirection by the court, in charging the jury that interest was to be given as a matter of law, whereas it was in the discretion of the jury. This point was not discussed at the trial, and no opinion given on it by the court. A new trial was granted on the first ground.

775

The opinion of THE COURT in granting a new trial was delivered by HOPKINSON, District Judge.

The contract in this case was proved, as it was alleged, by the plaintff, and the violation of it on the part of the defendant, without any legal warrant or justification, was shown to the entire satisfaction of the court. The plaintiff, therefore, had a clear case, and was entitled to a verdict. The cause was tried with ample preparation on both sides, with great deliberation and ability; and the jury, after hearing it fully discussed by the counsel, and receiving an elaborate charge from the court, rendered a verdict for the plaintiff, and assessed his damages at the sum of 5391 dollars 18 cents.

The plaintiff moved for a new trial, and in support of his motion has filed various reasons, the argument of which has brought the whole case into the review of the court. We are now to decide upon the motion; another trial is asked. 1. Because the damages are excessive.

In assessing the damages for the breach of a contract like the present, the law has established a rule for both the court and jury, which, if it may fail sometimes to do exact justice in a particular case, affords generally as equitable and reasonable a rule as could be given. The damage to be recovered is to be governed by the price of the article at the time when it should have been delivered, compared with the contract price. This rule is founded on an hypothesis not always true in fact, perhaps not often so, and very favourable to the plaintiff; that is, that he would certainly have sold the article, if he had received it, at the advance of that day, and not have retained it subject to the contingency of a depression. It is also true, on the other hand, that he must be content with the price of that day, and cannot claim the benefit of a subsequent increase of value. Before we inquire, from the evidence, what was the price of coffee on the day the defendant was bound to deliver this parcel to the plaintiff, we must settle the true meaning or interpretation of the rule, what is intended by the price of the article? On the one side it is contended that the plaintiff is entitled to recover so much money from the defendant as on that day would have enabled him to purchase the coffee; to make good the contract, and put into his possession the article the defendant had contracted to deliver to him; in short, to compel against him a specific performance of his contract. We do not inquire whether there would be any thing unjust in this rule—any thing of which one has a right to complain who has broken his engagements. But is it the rule which the law has adopted? Does it not introduce a new rule and a new principle into such cases? It is the price—the market-price of the article that is to furnish the measure of damages. Now what is the price of a thing, particularly the market price? We consider it to be the value—the rate at which the thing is sold. To make a market there must be buying and selling, purchase and sale. If the owner of an article holds it at a price which nobody will give for it, can that be said to be its market value? Men sometimes put fantastical prices upon their property. For reasons personal and peculiar, they may rate it much above what any one would give for it. Is that its value? Further, the holders of an article, as flour for instance, under a false rumour, which if true would augment its value, may suspend their sales, or put a price upon it, not according to its value in the actual state of the market, or the actual circumstances which affect the market, but according to what, in their opinion, will be its market price or value, provided the rumour shall prove to be true. In such a case, it is clear that the asking price is not the worth of the thing on the given day, but what it is supposed it will be worth at a future day, if the contingency shall happen which is to give it this additional value. To take such a price as a rule of damages, is to make a defendant pay what never in truth was the value of the article, and to give the plaintiff a profit, by a breach of the contract, which he never could have made by its performance.

The law does not intend this: it will give a full and liberal indemnity for the loss sustained by the injured party, and means to impose no higher penalty than this on the defaulter. With this explanation of the rule which prescribes the market price of the article on the day of delivery, we must examine whether the jury in this case have executed it clearly in the verdict which they have rendered. It is conceded by both parties that they have calculated the coffee which the defendant was bound to deliver to the plaintiff on the 14th of April, 1825, at 19¾ cents a pound. Does the evidence support this calculation or estimate for such coffee, or so large a quantity on that day? Was this the buying and selling price? We feel, as the jury probably did, no inclination to force the testimony in favour of the defendant; on the contrary, his unaccounted for and unaccountable conduct in this affair; ‘the carelessness, to say nothing more harsh of it, with which he disregarded a deliberate, and to him a profitable contract, was calculated to induce a jury to go all allowable lengths against him. The reason he gave for refusing to perform his bargain with the plaintiff, has been given up at the trial, and never had any solid foundation even in his own opinion. The ground taken for his justification or apology here, so far as appears by the evidence, did not occur to him at the time of the transaction, and of course formed no part of his motive or reason for receding from his engagement. Unwilling to impute to Mr. Welsh a sordid design, we confess ourselves unable to discover the cause of his departure from the course it

776

was so obviously his duty to pursue. If such considerations have influenced the jury, and very naturally too, in making up their verdict, we must not allow them to affect our judgment of the law of the case, and the application of it to the evidence. Juries may sometimes yield, honestly, to excitements, which judges must not feel. To correct such errors is a prominent use of the calm review of a case on a motion for a new trial. The question of market value is one so peculiarly proper for the decision of a jury, that we would not oppose ourselves to their opinion upon it, unless where we are assured that they have either mistaken the rule of law, or contradicted the clear purport of the evidence. “We inquire then, have the jury erred on this point, and given to the plaintiff a higher rate of damages than he is entitled to; that is, have they estimated the coffee, which was the subject of the contract, at a greater value than it had in the market on the 14th of April, 1825? On a careful examination of the testimony of very intelligent witnesses, well acquainted with the subject, we cannot believe that the value of this coffee was, on that day, so high as 19¾ cents a pound, or that the plaintiff, had it been duly delivered to him, could have obtained any such price for it. Mr. Stacy's quotation of prices to his correspondent in his letter of the 12th, gives no sales or other facts on which this opinion, for it is no more, was founded; nor the quality or quantity to which he applies it; and it is to be recollected too, that Mr. Stacy was a seller, and that Mr. Linn on this same 12th inst. offered, but could not get 19 cents for Mr. Stacy's coffee. As to the day in question, and which, in such a fluctuating market, must be particularly looked to, we have no evidence of value or price, either by actual sales or other data, in relation to coffee on that day.

There was a sudden and considerable excitement in the coffee market on the 7th, founded on circumstances and expectations which were not afterwards confirmed; and no sales were made from that day to the 14th inclusive, which, in our minds, show such an advance as would have raised the value of this coffee to the price at which it has been estimated by the jury. Whatever prices the holders may have asked, no one was willing to give them; but on Tuesday, the 12th, Mr. Linn offered any he had at 19 cents, and could get no bid. We forbear to make a more minute examination of the testimony, or to express a more precise opinion upon it, as it may again come under our judicial investigation. It is enough that we think' the jury have so far overrated the value of this coffee, as to support the objection of excessive damages to their verdict It is not unlikely that they may have not exactly understood what was the meaning of the court in instructing them in the range they might take between the lowest and the highest price, as they might deem the refusal of the defendant to perform his contract to be wilful or inadvertent; proceeding from an unjust violation of his engagement, or a conscientious, although mistaken view of the obligation. While we then thought, and now think, that the jury might take such matters into their consideration in assessing the damages, we did not intend that they should go out of the limits of the market price, nor take as that price whatever the holders of coffee might choose to ask for it; substituting a fictitious, unreal value, which nobody would give, for that at which the article might be bought and sold. It has even grown into a proverb, that a tiling is worth what it will bring, not what the caprice or speculating anticipations of its owner may induce him to ask for it.

Being of opinion, on this first reason, that it is well maintained, and that the verdict ought to be set aside on account of the excessiveness of the damages, it is unnecessary to give any opinion on the other reasons filed and argued by the defendant.

We think it is not going out of the path of our duty to suggest that as the right of the plaintiff to a verdict seems to be well established, and the question is only about the amount he should recover, we may recommend a settlement of this matter by the parties, or their counsel or friends; thus avoiding an expensive, troublesome and unpleasant litigation.

1 [Reported by Hon. Henry Baldwin, Circuit Justice.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.