Case No. 1,061.

BARRY v. GUGENHEIM et al.

SAME v. EVERETT.

[5 Fist Pat. Cas. 452;1 1 O. G. 382: Merw. Pat. Inv. 242; 2 Bench & Bar, 65.]

Circuit Court, E. D. Pennsylvania.

April Term, 1872.

PATENTS FOR INVENTIONS—SPECIFICATIONS AND MODEL—TIN CANS.

1. It is not sufficient that the parts or features of a machine which are essential to the production of the proposed result he shown in the patent office model. If the inventor desires to appropriate them, he must so inform the public by his specification; and if they are not so described, whether they relate to the construction or the mere adjustment of the machine, their use by others is not unlawful.

[Cited in Couse v. Johnson, Case No. 3,288.]

2. If the essential parts or features of a machine are such as the experience of a mechanic, skilled in the art, would devise or apply in the operation of the machine, a patentee can have no exclusive right to their employment.

3. Where the seam between the body and the cover of a metallic can had been closed by compression between revolving swages, so adjusted that their beveled faces were parallel to each other: Held, that a change in the adjustment which destroys the parallelism of these faces, for the purpose of producing a wider and smoother seam, belongs to the category of mechanical skill.

4. Where one swage was described as having a beveled periphery, and the swage with which it operated as having “a corresponding beveled periphery,” these terms import that the beveled surfaces were parallel.

5. Letters patent for an “improvement in machine for making tin cans,” reissued to Christian Barry, October 6, 1868, are void for want of novelty.

[In equity. Bills by Christian Barry against Gugenheim, Dreyfus & Co. and against Horace Everett] Final hearing on pleadings and proofs. [Bills dismissed.]

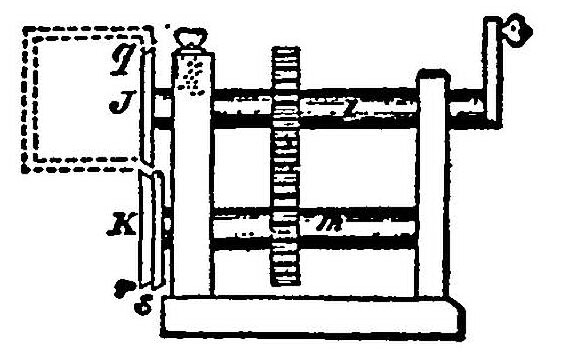

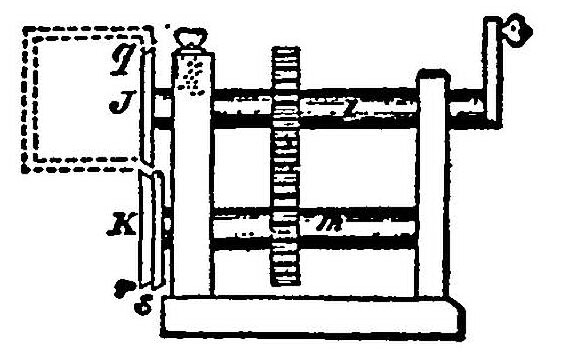

Suit brought on letters patent [No. 71,680] for “improvement in machine for making tin cans,” granted to complainant December 3, 1867, and reissued October 6, 1868, [No. 3,143.] A suit by the same complainant against Horace Everett was argued at the same time. The nature of the invention Is sufficiently stated in the opinion, and will be readily understood with the aid of the accompanying engraving, in which J and K represent the swaging rollers, and the dotted lines, a can passing between them.

T. A. Burton, for complainant.

J. B. Gest for defendants.

MCKENNAN, Circuit Judge. Both these cases present the same questions, and have been submitted upon the same proofs. They involve the consideration of only the third claim of the complainant's reissued patent This claim is for part of a tool for closing the top and bottom, or the cover and the body of metal cans, so as to make, them airtight without the use of solder, and is in these words:

“3. The swage or die, J, having beveled periphery, q, and swage or die, K, having a corresponding beveled periphery, r, operating together, substantially as described, for the purpose specified.”

The swages thus described are attached to the ends of horizontal shafts carrying cogwheels working into each other, and having their bearing upon the standards of an upright frame. These shafts are made to rotate in opposite directions by a crank-handle attached to the upper shaft By a preliminary process, the can-body and the top and bottom lids are prepared for the operation of the closing machine. The cylinder or canbody Is flared outward, and the lids intended to close the ends of the can are countersunk to a depth corresponding with the flare of the body, with an extension of their rims so as to allow them to lap over on the outer side

948of the flared ends of the body. This extension is bent downward, forming a hookshaped figure. The lid, thus prepared, is then put on the body, and the open seam thereby formed is placed between the swages of the closing tool, and, by their rotation and compression, the flared part of the body and the hooked rim of the lid are brought into close contact, producing a tight, smooth joint, composed of three layers of the metal. It is the simple office of the closing-tool to make this seam, and it is effected by the inward and outward bevels of the periphery of the swages and their rotary compression of the parts to be brought into close contact. This is the essential purpose of the invention as described in the specification.

The invention of this tool is claimed by the complainant, and, as before stated, is the subject of the third claim of his reissued patent dated October 6, 1868. Its novelty is denied by the respondents; and, as the proofs sustain this denial, it is necessary only briefly to advert to this point of the defense.

The complainant's original application was filed October 25, 1867, and the earliest period to which the proofs carry back the date of his alleged invention is October or November, 1865. This is the import of the testimony by Julius Zabel, who says he made wheels for the complainant, like those in his exhibit No. 6, for closing boxes, in one or the other of these months in that year. Aside from the general statements of several witnesses, that sunken headcans closed from the outside were well known for years before the complainant's alleged invention, and that the tool for thus closing them was, in principle and operation, like his, one machine at least has been exhibited in evidence which disproves the novelty of the complainant. It is the machine made by Henry Diedricks for McCoy & Snell. There is no dispute that Diedricks made such machine for McCoy & Snell; and in both the principle and result of its operation it cannot be substantially discriminated from the complainant's. The most earnest contention has reference to the time when it was made and used. I do not propose to discuss in detail the evidence on this, point, but only to state that it satisfactorily proves this machine to have been completed and worked in the early part of 1865, antedating the complainant's machine some nine months.

It is sought to invest the complainant's machine with the peculiar result of producing a wider and smoother seam than any of its predecessors was capable of producing, as the result of a want of parallelism in the beveled faces of its swages; and it is consequently urged that it is thereby to be distinguished as a novel invention from any other closing-machine. This suggestion seems to have originated with S. Lioyd “Wiegand, an acute and intelligent expert, who was examined as a witness for the complainant, and elaborates it in his testimony. It is a sufficient answer to it to say that a difference in the taper of the bevels of the rollers is not stated or indicated in the complainant's specification as a part of his invention, or as essential, or even important, in producing the result proposed by him. Mr. Wiegand says it is shown in the model deposited in the patent office, but that will not supply the omission of a reference to it in the specification. If it is a peculiar feature of the complainant's machine, and he desires to appropriate it, he must have so informed the public by his specification, or he can not claim an exclusive right to it. The very object of the specification is to furnish the public with a description of the invention in such “full, clear, and exact terms” that any one skilled in the art to which it appertains may make, construct, and use it, and, without subtraction from or addition to the means specified, produce the precise result described by the inventor. It must, therefore, distinctly indicate the parts or features of a machine which are essential to the production of the proposed result. If they are not described, whether they relate to the construction or the mere adjustment of the machine, their use by others is not unlawful. If they are such as the experience of a mechanic skilled in the art would devise or apply in the operation of the machine (and to this category is to be assigned the peculiar adjustment of the rollers in the complainant's machine according to the clear import of Wiegand's testimony), the patentee can have no exclusive right to their employment.

But there is another reason why the suggested discrimination is unwarranted. It is inconsistent with the testimony of the specification. By the third claim the swage, J. is required to have a beveled periphery, q, and the swage, K, is to have a “corresponding beveled periphery, r.” Can this mean anything else than that such bevel is to be made with the same inclination or angle? How can they be said to correspond unless their surfaces are parallel? But this is rendered clear by the drawing referred to and made part of the specification, in which the working faces of the rollers are shown to have a corresponding inclination and exactly parallel lines. It results, therefore, that deviation from parallel fines in the working faces of the rollers is not an appropriate feature of the complainant's machine, and that it can not for that reason be distinguished from the other machines exhibited in evidence.

The machine made for McCoy & Snell is constructed with an upper and a lower swage, correspondingly beveled, and is adapted to produce the same result as the machine described in the complainant's patent. As it was completed and worked before the complainant devised his, his alleged invention lacks essential elements of novelty.

The bills in both cases must, therefore, bedismissed with costs.

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Pisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission. Merw. Pat Inv. 242, contains partial report only.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.