Case No. 754.

2FED cas.—26

BAIN v. MORSE.

[1 MacA. Pat Cas. 90; 6 West Law J. 372; 48 Jour. Fr. Inst. 58.]

Circuit Court, District of Columbia.

March, 1849.

PATENTS FOB INVENTIONS—APPEAL—INTERFERENCE.

[1. Under the provisions of the act of congress of July 4, 1836, (5 Stat 120, c. 357, §8,)that, if an application be made for a patent that may interfere with patents issued or for which applications are pending, the commissioner shall give notice to applicants and patentees; that, if either be dissatisfied with the commissioner's decision “on the question of priority of right or invention,” he may appeal there from; and that “proceedings shall be had to determine which, or whether either, of the applicants is entitled to receive a patent,”—the jurisdiction of the appellate tribunal over the question of priority of right or invention only arises where there is an interference, and on appeal the question of interference, as well as the question of priority of right, comes before the court for review.] [Cited in Yearsley v. Brookfield, Case No. 18, 131.]

[2. The interference coming before the court for review on appeal under the act of July 4, 1836, (5 Stat. 120, c. 357, § 8,) is only an interference with respect to patentable matters; and, in deciding the question, the claims of the applicants must be limited to the matters specifically set forth as their respective inventions.]

[3. The applications of Morse (afterwards patent No. 6,420, May 1, 1849) and Bain (afterwards patent No. 6,328, April 17, 1849) purported to disclose a new system of telegraphy, consisting in the production of marks or discolorations on paper “chemically prepared” by the direct action of the galvanic current, and without the intervention of magnets or other intermediate devices. Both inventions proceeded upon the theory that the passage of a galvanic current through paper or other suitable material previously treated with any one of a variety of chemical solutions will produce discolorations or marks corresponding in number and length with the pulsations of the current. In the Morse apparatus the operator at the sending station produces currents corresponding to the dots and dashes of the Morse alphabet by the ordinary Morse key. At the receiving station, the prepared strip of paper is drawn by a register between a metallic cylinder or drum mounted upon a suitable standard, and a thin edged platinum wheel held in contact with the strip by a metal spring, mounted upon a metal standard. The passage of the alternating currents from the platinum roller to the cylinder or drum through the strip produces the discolorations or marks which form the message. Morse claimed “the use of a single circuit of conductors for the marking of telegraphic signs, already patented, for numerals, letters, words, and sentences, by means of the decomposing, coloring, or bleaching effects of electricity acting upon any known salts that leave a mark, as the result of the said decomposition, upon paper, cloth, metal, or other convenient and known markable material.” He also claimed the invention of the machinery described for the purpose stated. Bain's invention was designed to transmit a message through one machine by a single operation to any number of distant stations. The transmitting and receiving wires are combined in a single apparatus, one of which is placed at each station. The circuits are changed to transmit or receive at pleasure. The message is prepared or “composed” in permanent form by providing a slip of paper with perforations corresponding in length and arrangement with a predetermined system of signs or characters. This sending slip is wound upon a suitable roller, and is caused to pass between a transmitting roller and a comb or brush, which are normally in circuit. The nonconducting slip interrupts the flow of the current, except at such times as the perforations therein permit the brush to contact with the roller. By passing this slip between a number of transmitting rollers and brushes in separate circuits, but arranged in line in one machine, the message can be simultaneously transmitted to an indefinite

395number of stations. In the receiving devices, the prepared paper is wrapped around cylinders or drums. When the cylinders are revolved at a regular speed, they are caused to traverse across the machine under a stylus or contact point, whereby the marks or discolorations are disposed in a regular spiral around the cylinder, and the message is read in lines from left to right, in the ordinary manner of writing or printing, when the sheet is unwound. Held, that as the battery, the circuit, the prepared paper, and the marking by the electro-chemical process were not new, and were not patentable by either party, the Morse invention must be restricted to the machine or apparatus by which he combined these elements, and produced the marks; that, as thus restricted, there was no interference between it and the Bain apparatus; and that letters patent should issue to Bain for his invention.]

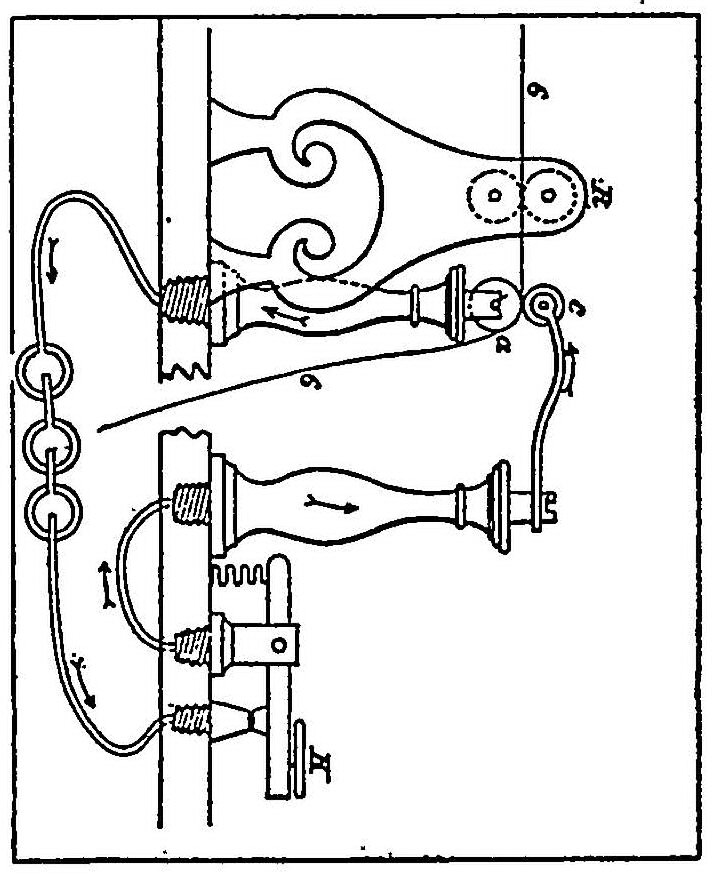

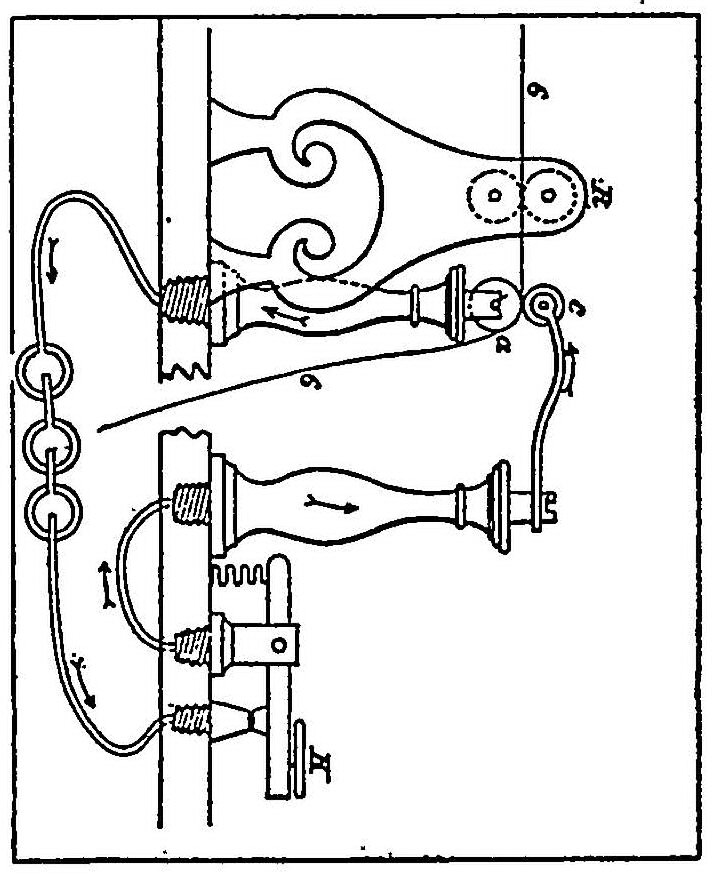

[Appeal from the commissioner of patents.] The applications in this case (afterwards patents to Morse 6420, May 1st, 1849, and to Bain 6328, April 17th, 1849) purported to disclose a new system of telegraphy, which consisted in producing marks or discolorations on paper “chemically prepared” by the direct action of the galvanic current, and without the intervention of magnets or other intermediate devices. The inventions of both parties proceeded, upoin the theory that the passage of a galvanic current through paper or other suitable material previously treated with any one of a variety of chemical solutions, as iodide of tin, sulphate of iron, acetate of lead, iodide of potassium, &c, will produce discolorations or marks corresponding in number and length with the pulsations of the current. The apparatus of Morse, as illustrated in the subjoined cut, was quite simple.

The operator at the sending station produces the alternating currents corresponding to the dots and dashes of the Morse alphabet by the ordinary Morse key K. At the receiving station the prepared strip 6 is drawn by a register B between a metallic cylinder or drum, a, mounted upon a suitable standard, and a thin edged platinum wheel c, held in contact with the strip by a metal spring mounted upon a metal standard 6. The direction of the current is indicated by the arrows. The passage of the alternating” currents from the platinum roller to the cylinder or drum through the strip produces the discolorations or marks which form the message.

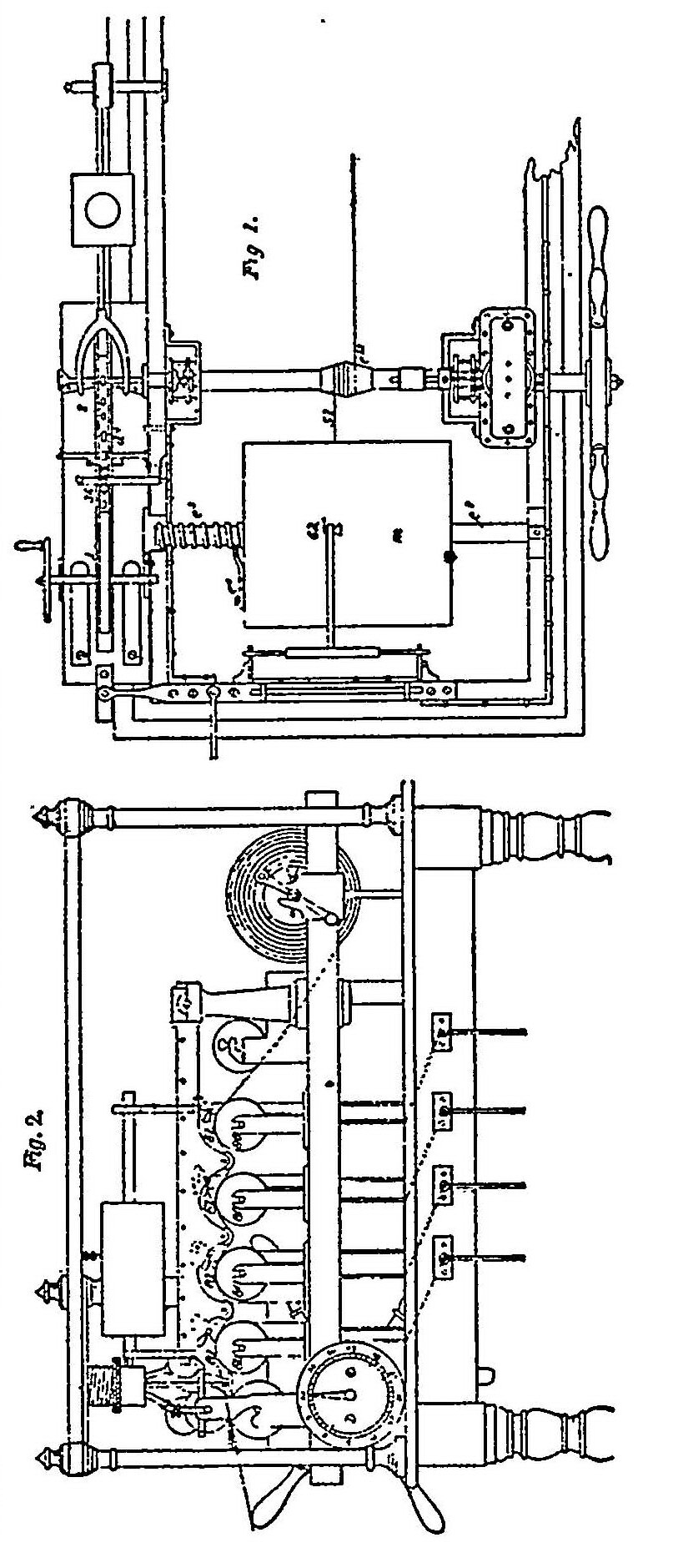

Bain's invention was designed to transmit a message through one machine by a single operation to any number of distant stations. The transmitting and receiving wires are combined in a single apparatus, one of which is placed at each station. The circuits are changed to transmit or receive at pleasure. Fig. 1 is a plan view, showing the general arrangements only. Fig. 2 shows the devices for transmitting to a number of stations.

The message is prepared or “composed” in permanent form by providing a slip of paper with perforations corresponding in length and arrangement with a predetermined system of signs or characters. This sending-slip 2 is wound upon a suitable roller 1, and is caused to pass between a transmitting-roller d4 and a comb or brush 36, which are normally in circuit. The non-conducting slip interrupts the flow of the current, except at such times as the perforations therein permit the brush to contact with the roller. By passing this slip between a number of transmitting-rollers 80 and brushes 81 (Fig. 2), in separate circuits, but arranged in line in one machine, the message can be simultaneously transmitted to an indefinite number of stations. The receiving devices are shown in the centre of Fig. 1. The prepared paper in the form of sheets is wrapped around cylinders or drums M (one of which is shown), either of which can be used while the other is being prepared. Steel slips or tongues e4 on the cylinder take into a screw-thread e3 on the fixed-shaft e2. When the cylinders are revolved at a regulated speed by the cord 51 and the pulley e12 they are caused to traverse across the machine under the stylus or contact point 62, whereby the marks or discolorations are disposed in a regular spiral around the cylinder, and the message is read in lines from left to right in the ordinary manner of writing or printing when the sheet is unwound.

R. H. Gillet, for Mr. Bain.

1. Morse has not filed sufficient drawings nor deposited a sufficient model of his invention, nor has he described it in such full, clear, and explicit terms as to enable a person skilled in chemistry, electricity, and mechanics to construct and use the same to transmit intelligence. A local circuit only is shown; no centre connections are shown, nor any means of operating over long distances. No mode of preparing the paper chemically is described which is adequate to produce the results claimed. No telegraphic or other machinist can produce an instrument that will operate as and to the extent which Morse claims, and no chemist can produce the results he describes by complying with the specification. No evidence on this point was produced before the commissioner or is now before the judge. The reviewing tribunal is without any guide, except personally to read the specification and claim, and to examine the model and drawing of Morse's application, and determine whether by following the directions contained therein anything useful or important can be produced. The commissioner and examiners may be called by either party to testify under oath “in explanation of the principles of the machine or other thing” for which a patent is asked, but they cannot state facts or give opinions on other subjects. Bain denied the practicability of Morse's invention before the commissioner, and offered to go into proof upon that subject before the final hearing. The utility of his own invention was not denied. Under these circumstances, there was error in the decision of the commissioner in not ruling against Morse's claim; and the proper mode of correcting that error is to open the case for the production of full testimony on both sides.

2. There is in fact no real and substantial interference between the two applications. The underlying principles common to both machines are old, as admitted by the commissioner. The single circuit, the signs, and the use of chemically-prepared paper are separately old, and the invention of each party is restricted to his own particular combination and arrangement of devices by which these common principles are carried into effect. Bain uses chemical agents and the long telegraphic circuit, the earth making part of it, in a particular manner to produce the consequences which he describes. From a comparison of the drawings and models it will be apparent that the machines differ in form and substance. Morse's machine is incompetent to produce the effects described by Bain, if susceptible at all of practical use. It is denied that any operative machine could be produced by following the directions of those specifications. In a case of this kind proof should be resorted to.

3. The commissioner erred in allowing Morse to go into proof of his invention prior to his caveat and application, and at the same time refusing to allow Bain to make proof of his discovery before the date of his English patent of 1846. Unless the statute creates a difference in clear terms, the parties stand upon an equal footing before the patent office in all respects. The sixth section of the act of [July 4,] 1836, [5 Stat. 119,] removes the previous disabilities of foreigners, and declares that all persons may obtain patents under the circumstances and conditions therein named. The ninth section, it is true, raises a distinction between foreigners and citizens with respect to the payment of fees, requiring a citizen to pay §30, and a subject of Great Britain §500, and other foreigners §300. The question is whether a foreigner, having paid the requisite fee, is to be permitted to substantiate his right to a patent conferred upon him in terms by the sixth section, by showing, upon an issue of priority properly joined, when he in fact made the invention. No claim in the statute in terms makes this distinction between citizens and foreigners, whether they are prosecuting their cases ex-parte or in interference. The seventh section, to which reference is made, relates exclusively to the ex-parte examination of an application. It provides that the commissioner shall in all cases issue a patent if it shall not appear, among other things, “that the same (invention) had been invented or discovered by any other person in this country prior to the alleged invention thereof by the applicant.” This claim does not prohibit the foreign inventor from showing the date of his

397invention and obtaining a patent, but provides that such prior discovery, if not patented or described, will not prevent the American inventor from also obtaining a patent for the same. Nor does the proviso of the fifteenth section of the act furnish any rule governing the issuance of patents. The proviso in question declares that no patent, in a suit brought thereon, shall be held to be void on account of the invention, or any part thereof, having been before known or issued in any foreign country. It does not appear, however, that in such a case the plaintiff could recover. By the enabling clause of the section judgment will be rendered for the defendant, with costs, if it shall appear, among other things, that the patentee was not the first and original discoverer of the thing patented, while the later American inventor cannot recover against a prior foreign inventor; so there is nothing in the section to prevent the prior foreign inventor from sustaining his patent against all subsequent inventors.

The eighth section, establishing and regulating interferences, makes no exception against the foreign inventor.

Amos Kendall, [and with him Alexander H. Lawrence,] for Morse.

1. The only question submitted for decision in case of conflicting claims for patents is “priority of invention.” St. [July 4,] 1836, [5 Stat 120,] § 8; St [March 3,] 1839, [5 Stat 354,] § 11.

2. The appeal in such controversies must be decided in a summary way on the evidence produced before the commissioner. St [March 3,] 1839, [5 Stat 354,] § 11.

3. The chief justice has no authority to receive additional testimony, except that of the commissioner or examiners of the patent office, and that only “in explanation of the principles of the machine;” (Act 1839, § 11;) nor has he authority to return the case to the patent office for the purpose of taking additional testimony.

4. All the allegations and arguments of the other side, therefore, involving the questions of utility, novelty, and patentability are irrelevant and aside from the point at issue.

5. The contention by Bain that there is no conflict between his claims and those of Morse is an admission that Morse is entitled to all he claims. In this view, Bain should disclaim all that Morse claims, and go his way.

6. But there is an interference. Bain's third claim probably interferes with Morse's first claim. If granted, Bain could do all that Mr. Morse claims an exclusive right to do. He could write Mr. Morse's characters precisely as Morse does; and therein consists the interference.

7. Coming to the question of priority of invention, Morse was the first man in Christendom, so far as we are advised, who conceived the idea of a telegraph by the chemical action of the electric fluid. In his application he swears that he conceived the idea in 1832, and the affidavits filed show he was experimenting upon the idea at that time. This was before Davy, Bain, or any other European inventor, so far as we are informed, had considered the subject in 1846, as shown by the affidavit of his son, he had matured an Instrument; in June, 1847, he filed his caveat, and in January, 1848, applied for a patent. By that time he was cut out, like all other inventors, from claiming the general principles of the apparatus by Davy's patent, dated July, 1838, and enrolled January, 1839, which disclosed the use of several circuits for marking parallel series of signs or discolorations, and by Bain's patent of 1843, for copying surfaces by the use of a single circuit of conductors.

8. Can a foreign inventor go behind his foreign patent to prove priority of invention Mr. Bain says he can. The patent office and the attorney-general say he cannot. It is said that the citizen and an alien, neither having a patent abroad, stand on the same footing with respect to application for patent, in this country, and have the same latitude in proving priority of invention. It is sufficient to say that this is not the state of facts before the court. In this case the alien has a foreign patent, and the question is, can he go behind that patent. The privilege is claimed for Mr. Bain for the purpose of putting him on an equality with Mr. Morse. It is singular that Mr. Bain does not perceive that the privilege he claims is not allowed to American citizens. If Mr. Morse had applied for a patent the same day that Mr. Bain did he could not have obtained one, because Mr. Bain had a patent for the same thing in England. The patent office could not allow him to go behind Bain's foreign patent to prove priority; yet it is maintained that Bain himself is subject to no such limitation. Aliens are those to be preferred to citizens. It is only when the application for a patent has been made here before the date of the foreign patent that the citizen is permitted to go behind that patent to prove priority of invention. See, however, Bartholemew v. Sawyer, [Case No. 1,070,] and later cases. If Mr. Bain had made an application here before he took out his patent in England, he also could have gone behind that patent to prove priority. In point of fact, therefore, the law and the decisions of the patent office place the foreigner and citizen upon precisely the same footing in these respects; and the reason Bain cannot go behind his foreign patent is because he made no application for a patent here until after he got one there.

9. The commissioner of patents is arraigned for deciding that in the eye of the American law the specification forms a part of the English patent, and that the date of enrollment, and not the date of sealing, is the true date of such a patent. He might have gone further, and stated that, in the eye of the English law, the specification is part and

398parcel of the patent. Hindmarch on Patents. Every patent issued in England is an incomplete instrument until the specification be enrolled; and if it be not completed by enrollment within six months, the inchoate grant becomes absolutely void. Specifications in England sometimes embrace inventions not thought of when the patent was sealed. It cannot be supposed that an invention so made or incorporated into the English patent would bar an American discoverer whose invention was subsequent to the sealing of the patent, but prior to the invention of the Englishman and the sealing of his caveat. Such a state of the law would open the door to great frauds. It is not necessary for Morse to describe fully or at all the chemical solutions used by him. Their capacity to make marks by the action of electricity was well-known, and is not here claimed. It is well-settled law that a patentee need not de scribe in his specification things used by him which are well-known, and also that a specification which, instead of describing a well-known thing, refers to a description given in a prior patent, is good.

The following extracts are taken from the reasons of the commissioner in support of his decision:

The decision implied that the invention (regarding the claims of both parties as the same) was new, original, useful, and therefore patentable. It implied, also, that the materials and mechanism, and the modus operandi, as set forth by both parties, were adequate to the results claimed, and that the specifications, drawings, and models of both parties were in substance sufficient to enable the undersigned to understand and comprehend the invention, as well as persons skilled in the particular art to which it relates. All these questions were preliminaries to the question of interference, and are not, therefore, in the opinion of the undersigned, involved in this appeal. The only question involved in the interference declared to exist between the claims of the two parties is the priority, according to the patent law of the United States, of their respective inventions of the matters claimed by each of them as new and original. * * *

The undersigned has decided that the drawings, models, and specifications were sufficient in both applications before he adjudged the interference. The sufficiency of the models, drawings, and specifications is a question, so far as it affects the issue of a patent, which is reserved alone for the commissioner. He determines it upon the evidence submitted by the party making the application. That evidence is the model, drawings, and specifications. The law has made no provision for trying the question in any other way. It has made no provision to allow any party or person to come in and offer testimony to show the insufficiency of the models, &c., of an applicant for a patent. There is no mode pointed out by law for trying the question. * * *

It is proper to remark, further, that Bain offered no evidence to the commissioner of the insufficiency of Morse's model, &c. He merely alleged in argument that they were not sufficient. The commissioner, therefore, had no other evidence before him than the model, &c, and upon that evidence he decided that they were sufficient. As no question as to the admissibility or inadmissibility of evidence on this point came before the commissioner, it is not a proper matter to bring before your honor on this appeal. See section 11, Act Approved March 3, 1839, [5 Stat. 354.] The said Bain alleges, as his second reason for the reversal of the decision of the undersigned, that “there is in fact no real and substantial interference between the two applications.” The reply to this reason is substantially set forth above in the answer by the undersigned to the first reason for the reversal of his decision. But, in further reply, the undersigned states that, in support of the proposition contained in his second point, the said Bain supposes a case in which the same ends, being attained by different means, would not justify an interference. It is admitted that some of the features of Bain's invention differ from any found in Morse's; and Bain's claims to these particulars constitute no part of the interference between the two contestants; nor is a patent for those parts refused.

But, as has been before stated, the principal claims in the two applications were identical in substance, and it was upon them that the interference was declared. Parties, however, may come in direct conflict in their claims, though each may use different means to attain the same ends. Such cases often occur. Suppose, for instance, said Bain and Morse both used a chemically-prepared paper upon which to make telegraphic signs, and that each of them described paper prepared with such chemicals as they preferred to use, both differing as to the kind of chemical material adopted, and neither laying any special claim to their own chemicals for this purpose, but both claiming broadly the use of chemically-prepared paper for making these marks as telegraphic signs,—can it be doubted in such a case that an interference exists; that the claims, and in fact the inventions, are identical?—for neither party will limit his invention to the use of a special kind of paper. Indeed this would be obviously futile. It is plain, then, that some of the means may differ, and yet the inventions, in all patentable particulars and claims, be the same. If either party should attach any value to the special points of difference, he should lay separate claims to them. The interference in the present case was declared only upon those claims actually conflicting, and the parties so notified. The objection by Bain that Morse's invention

399was impracticable, because be did not describe a long telegraphic circuit, or the use of the earth as a part of the circuit, must be regarded as a cavil. All inventions for telegraphing by galvanism are of necessity made upon the supposition of a long circuit, though the experimental trials may be made through only few feet of wire. A long telegraphic circuit has no special signification in this case, and neither party claims a long or a short circuit or using the earth as a part of the circuit The earth has been used as a part of the circuit in Morse's telegraph since its first establishment. A single circuit, however, has a special meaning and importance in both their present inventions. It is plainly demonstrable, in fact it must necessarily follow, that a plan of operations which will work successfully in a small room will work equally well upon the most extensive scale, provided the galvanic force be increased in the proper proportion to the increase of the extent of the circuit * * *

The said Bain, as the third ground of appeal from the decision of the undersigned, alleges “that the commissioner should have declared the true date of Bain's patent to be the one appearing on its face, to wit, December 12th, 1846, which was before Morse's application or caveat.” In order that your honor may fully understand the nature of the decision of the undersigned upon this point, and therefore be better enabled to judge of its correctness, he will proceed briefly to state its nature and the grounds on which it was made. The decision, in short, was, that in cases affecting the rights of other persons claiming priority or originality of invention, the true date of the English patent is the day of the enrollment of the specification, and not the day of the sealing of the patent. The grounds of the decision are to be found in the following facts and considerations: The English patent law provides that the inventor may file in the appropriate office the title of his invention, describing it briefly, and have his patent sealed; he is then allowed four months, if he does not intend to procure a patent in Scotland, or six months if he does so intend, to enroll in the appropriate office a full and complete description of his invention, technically called a specification, duly executed under hand and seal, when his right to the exclusive privilege which the patent secures becomes perfect and absolute. Until this full and complete description or specification is enrolled, the public are not advised of the particular nature of the invention of which he claims to be the author. This information he is bound to give, by the enrollment of his specification within the four or six months, as the case may be, or his patent becomes void. Until this enrollment of his specification, the patent is an imperfect or inchoate instrument, liable to be defeated by the non-performance with the time specified, of the condition on which it was granted. It is not a perfect, complete, and absolute instrument until this condition is performed. Therefore, until the inventor has enrolled his specification, it may in truth be said, notwithstanding his patent has been sealed, that his invention has not been patented. Such, in substance, are the provisions of the English law with regard to the patenting of inventions. See Hind. Pat pp. 70, 71, 157, 158.

The law and practice of this country are different. Here it is required that the model, drawings, and specification shall be filed, the invention examined, the patent recorded on the records of the patent office, and the specification enrolled on parchment and annexed to the patent before the instrument is sealed. In short, it is required to be a full, complete, and unconditioned instrument before it is delivered to the patentee. His title to his invention is absolute the moment his patent is sealed and signed by the proper officers. Our law knows no such thing as a conditional patent, liable to be confirmed or defeated by the performance or non-performance of some proviso or condition expressed in it. Its issue implies every requisite which is necessary to make it a valid and unconditional instrument, conveying to the patentee an absolute title to the invention which it describes. And in accordance with this view of the subject, our law, when it speaks of an invention as having been “patented” in this or a foreign country, implies that such foreign patent is perfect and complete, and not one liable to be defeated by the non-performance of a condition expressed in it Section 7 of the act of July 4, 1836, [5 Stat. 119,] makes it the duty of the commissioner to grant a patent to the applicant, provided his invention has not been “patented” or described in any publication in this or any foreign country. Now, how is it possible for the commissioner to know what has been patented in a foreign country if such foreign patent does not contain a full description (or specification) of the thing patented? Suppose, when Mr. Morse made his application for a patent for his invention, some English work had contained the general statement that Mr. Bain had had a patent sealed on a particular day for an electro-chemical telegraph; how is the American commissioner to know from that general description what that invention of Mr. Bain is, and whether or not it is the same which is claimed by Morse? The thing is impossible; and such impossibility shows conclusively the correctness of the construction which the undersigned has put on the word “patented” in our law. Therefore it cannot be said, in the meaning of the American law, that an invention has been patented in England, or anywhere else, until every condition necessary to make such patent complete and absolute has been complied

400with by the patentee; and, therefore, the true date of an English patent, when it comes in conflict with the rights of the American inventor, must be the day on which it became a complete, perfect, and unconditional instrument.

And this construction finds an analogy in the well-known principles of common law relating to the dates of deeds and other instruments of writing. An instrument in writing under seal does not become a deed until it is delivered, arid the day of its delivery is its true date. It may even be an impossible date—for instance, the 30th of February; yet if it was in fact executed on the first day of January, that would be its true date for all legal purposes. Deeds are also conditional, subject to be confirmed or defeated by the performance or non-performance of some stipulated act between the parties. It may depend also upon some event or contingency, which may confirm or defeat it. In all which cases it is an incomplete or imperfect instrument until the performance of the act or the happening of the event upon which its validity depends, and then it becomes an absolute and unconditional instrument or a nullity. These views seem so conclusive upon the mind of the undersigned that he does not deem it necessary to consider the question further, nor to follow the learned counsel for Mr. Bain, through the ingenious and elaborate argument which he has presented in support of his position, much of which might be very pertinent were the question pending before an English tribunal, under the laws of England, but is not pertinent before an American tribunal and under the laws of the United States. The undersigned respectfully refers your honor to his decision in this case for the precise nature of his adjudication on this point, and the reasons in favor of the same. It is proper to remark that our law makes provision for antedating patents in certain cases; but a patent cannot bear date before the day on which the application was filed in the patent office. The undersigned deems it proper to notice here an authority cited by the learned counsel for Mr. Bain, which he deems conclusive; which authority is found in an abstract of the English patent law prepared by an English solicitor of patents for the undersigned, and published in his annual report to congress for 1847, page 790. The correctness of that abstract is not affirmed by the undersigned, nor does he believe that it is a correct statement of the English law. He relies, rather, upon Hindmarch, an English author of high repute, before cited, for a correct statement of the English law on this point and its construction by the English courts of justice.

The said Bain assigns as his fourth reason why the decision of the undersigned should be reversed “that the commissioner erred in allowing Morse to go into proof of his invention prior to his caveat and application, and at the same time refusing to allow Bain to make proof of his discovery before the date of the English patent of 1846.” The correctness of the decision of the undersigned to which this exception is taken depends upon the question whether or not our law makes a distinction between the rights of an American applicant and a foreign applicant, as affected by a question of priority or originality. And on this point the undersigned can add but little, if anything, to the force of the cogent and luminous opinion of the attorney-general, to whom the question was submitted; which opinion accompanies the appeal, and to which your honor is respectfully referred. On reference to the seventh section of the act of 1836, it will be seen that there are two grounds on which the commissioner is bound to refuse a patent to the applicant, viz.: First, if the thing sought to be patented has first been “invented or discovered by any other person in this country;” and second, if it has been “patented or described in any printed publication in this or any foreign country.” If the thing has been invented by any other person in this country, but not described, the commissioner is bound to refuse a patent. But he is not bound to refuse a patent if it has been invented in some foreign country, but not “patented or described in some printed publication in this or some foreign country.” The principle that seems to be plainly laid down by our law with regard to the matter is, that in a contest for priority between two persons claiming to have invented the” same thing in this country priority as well as originality must be proven. But in a contest between a person who has made the invention in this country and one who has invented the same thing in another country, originality in the American inventor is sufficient ground for awarding the patent to him, although the invention of the other may have in fact been prior in point of time in a foreign country. This distinction is obvious and palpable, and is intended to protect the person who invents a thing in this country from being defeated in his rights by proof of the invention of the same thing in a foreign country, if such invention has not been patented or described as our law requires. The fifteenth section of the act of [July 4,] 1836, [5 Stat. 123,] recognizes this distinction in defining the ground and mode of defense in suits for infringement.

When there is no foreign claimant of the same invention, there can be no doubt as to the right of the American inventor, whether on an application for a patent or in a suit for infringement in the one case the American commissioner would be bound to grant the patent to the American inventor, the latter conforming to the provisions of the law with regard to the mode of making the

401application, notwithstanding the thing claimed as new had been “invented and discovered” in a foreign country, but had not been “patented or described in some printed publication in this or some foreign country.” And in an action of infringement, the defense that the thing in dispute had been “invented” in some foreign country, but not “patented or described,”

The learned counsel for Mr. Bain has, while arguing his fourth point, much to say with regard to natural right and the rights of foreigners. It is not proposed by the undersigned to go into any metaphysical disquisition upon natural rights, nor how much all rights of property depend upon positive law. He would simply remark, in reply to the learned counsel, that foreigners have no rights in other sovereignties than that in which they are born, except what has been expressly conceded to them by the sovereign power of the countries to which they may go. They cannot even enter the limits of a foreign jurisdiction except by permission, express or implied, of the sovereign power. They have no legal privileges in the country to which they go except what are expressly granted to them. And all privileges which they are permitted to enjoy are granted as matters of favor and not of right See Vatt Law Nat c. 7, § 94, and following sections; and Id. c. 8. But the right of the American inventor is recognized by the constitution. See article 1, § 8. The right may be extended to the foreigner, and it may be granted to him conditionally or in a qualified manner, or it may be absolutely refused; and this upon the general principles of national law which regulates the comity and courtesies of nations in their intercourse with each other. And the legislation of congress has been in accordance with this view of the subject. By the act of December [February] 21, 1793, [1 Stat 318, c. 11,] only citizens of the United States were permitted to take out patents. By the act of April 17, 1800, [2 Stat. 37, c. 25,] the privilege was extended to aliens having resided two years in the United States. By the act of July 13, 1832, [4 Stat 577, c. 203,] the privilege was extended to aliens resident who had declared their intention to become citizens. The privilege was further modified with regard to aliens by the act of July 4, 1836, [5 Stat 119.) The right of the foreigner to take out a patent in this country for an invention or discovery made by him is precisely what our law defines it to be, and no more. Our statutes are construed according to their true intent and meaning so far as they affect the rights of foreigners, but they are to have no forced construction for the benefit of aliens, because the latter have no constitutional rights here further than has been expressly conceded to them by the sovereign power of the Union. Without following the learned counsel of Mr. Bain through the various steps of his elaborate argument on this point, much of which is inappropriate and irrelevant, and based, upon a false assumption of facts, the undersigned again respectfully refers your honor to the able and conclusive opinion of the attorney-general herewith submitted, which in his view covers the whole of the question. That the commissioner would be obliged to issue a patent to “the inventor,” (as is so earnestly insisted upon,) if a foreigner, to the exclusion of the American inventor, whose invention was subsequent, might be true if the foreigner had made his invention “in this country.” Bain having made his abroad, does not come within the purview of our statute, even if his invention in point of fact was prior to Morse's. * * *

The learned counsel contends that the undersigned should have refused a patent to Morse on the ground that his invention was

402not of “practical utility.” The “practical utility” of an invention is seldom determined at the patent office. The term “utility” has received from the courts a legal interpretation. According to that interpretation, it means any degree of utility; not that it shall be more useful than others. By the term “useful inventions” in the patent act of the United States is meant an invention that may be applied to a beneficial use in society, in contradistinction to an invention which is injurious to public morals, the health, or the good order of society. Bedford v. Hunt, [Case No. 1,217;] Kneass v. Schuylkill Bank, [Id. 7,875.] It is not necessary that the invention should be of such general utility as to supersede all other inventions previously in practice to accomplish the same purpose; nor is it important that its practical utility should even be limited, for the law does not look to the degree of utility. [Bedford v. Hunt, supra.] Acting in conformity to the spirit of the authorities above cited, the question of utility, any further than it concerns the public morals, the health, and good order of society, is not one which is particularly inquired into by the commissioner of patents in determining the patentability of an invention. Indeed in some cases it would be impossible for him to decide whether or not a machine was practically useful. That, generally, must be ascertained by actual experiment, which it would be impossible for the commissioner of patents in most cases to make. Therefore the general rule adopted by the patent office with regard to inventions is to decide upon the novelty, priority, and originality, and leave the question of utility to the public and the courts of justice to settle. But, as before remarked, (in answer to Bain's first reason,) this question of utility was not raised by the interference. It was a point settled by the undersigned before he ascertained that the claims of the respective parties did interfere. He decided that the inventions of both were useful and patentable before he declared the interference. In deciding that both claims were substantially the same, he decided that both inventions were useful, and he decided upon similar testimony, viz., the models, drawings, and descriptions of the two parties. He did not, as is alleged, decide expressly that Bain's invention was useful. The question was never raised. And with regard to Morse's, he had decided that it was useful before Bain had contended that it was not. But it is respectfully submitted that the question of utility cannot be raised by any second party on the issue of a patent. The law points out no mode for testing in the patent office the practicability of an invention, except by the examination of the specifications, drawings, and model. It has provided no way to take testimony touching that question. In short, prior to the issue of a patent, it is a question reserved for the commissioner alone, to be determined on the case before him. If he doubts, he may require experiments to satisfy him. If he does not doubt, nobody else has a right to raise the question nor to contest the issue of the patent on that ground, and he is bound to grant it With these views, hastily put together, the undersigned submits the various questions raised by the learned counsel of Bain to the enlightened consideration and decision of your honor. All which is respectfully submitted.

Edmund Burke, Commissioner of Patents.

For convenience of reference, the opinion of the attorney-general upon the question of law presented in this case is given in full:

Sir: I have the honor to reply to your letter submitting an inquiry propounded by the commissioner of patents, whether a foreign patentee can go behind the date of his foreign patent and prove the actual date of his invention, in order to defeat the right of an American inventor, there having been no previous description of the invention in any printed publication; or, in other words, whether the fact of an invention or discovery abroad, which had not been patented nor described in any printed publication, will defeat a patent to an original inventor, who has invented or discovered the same thing in this country. The answer to be given to this inquiry depends upon the act of congress of July 4, 1836, [5 Stat. 119,] when the patent laws of the United States underwent a revision, and several important provisions were for the first time introduced. By the sixth section it is enacted “that any person or persons having discovered or invented any new and useful art, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement on any art, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter not known or used by others before his or their discovery or invention thereof, and not, at the time of his application for a patent, in public use or on sale with his consent or allowance as the inventor or discoverer, and shall desire to obtain an exclusive property therein, may make application in writing to the commissioner of patents, expressing such desire, and the commissioner, on due proceedings had, may grant a patent therefor.” The same section provides that “the applicant shall also make oath or affirmation that he does verily believe that he is the original and first inventor or discoverer of the art, machine, composition, or improvement for which he solicits a patent, and that he does not know or believe that the same was ever before known or used, and also of what country he is a citizen.”

Thus far the law is left substantially as it stood before, and, if not accompanied by any new provisions, would be controlled by previous adjudications, founded in a considerable degree upon enactments now become obsolete. But the seventh section introduces a new rule, which seems to be decisive of the

403question under consideration. It declares “that on the filing of any such application, description, and specification, and the payment of the duty hereinafter provided, the commissioner shall make, or cause to be made, an examination of the alleged new invention or discovery; and if, on any such examination, It shall not appear to the commissioner that the same had been invented or discovered by any other person in this country prior to the alleged invention or discovery thereof by the applicant, or that it had been patented or described in any printed publication in this or any foreign country, or had been in public use or on sale, with the applicant's consent or allowance, prior to the application, if the commissioner shall deem it to be sufficiently useful and important, it shall be his duty to issue a patent therefor.” The rule here prescribed to the commissioner is afterwards reaffirmed and carried out in the form of a proviso in the fifteenth section, prescribing a rule of adjudication, namely: “That whenever it shall satisfactorily appear that the patentee, at the time of making his application, believed himself to be the first inventor or discoverer of the thing patented, the same shall not be held to be void on account of the invention or discovery, or any part thereof, having been before known or used in any foreign country, it not appearing that the same, or any substantial part thereof, had been before patented or described in any printed publication.” While, therefore, the seventh section declares that a patent shall issue to the inventor (all other conditions being complied with) if the thing proposed to be secured had not “been invented or discovered by any other person in this country,” the proviso of the fifteenth section enacts that the patent shall not be held void (all other conditions being complied with) “on account of the invention or discovery, or any part thereof, having been before known or used in any foreign country.”

These provisions introduce an important modification of the law of patents, designed to protect the American inventor against the injustice of being thrown out of the fruits of his ingenuity by the existence of a secret invention or discovery abroad—that is to say, one not patented, and not described in any printed publication. It is well known that such secrets of trade exist in great numbers, and are designedly withheld from the public; and when, therefore, the American inventor has been so fortunate as to invent or discover the same thing, he is as great a public benefactor as if the secret did not exist in any foreign country. And it was the intention of congress to secure to him his rightful property in the result, and not permit it to be defeated by the foreign inventor coming forward afterwards either for a patent or without a patent. There is no more reasonable or just foundation or title of property than that which has been so imperfectly secured by law in the products of mind; and it is to be regarded as the presumed Intention of the legislature effectually to secure it in every case where the reason of the law will apply and the language used will admit of a favorable interpretation. In the present case the intention is clear, and the language explicit and unequivocal, leaving no room for construction. The proviso, without the aid of the sixth section, furnishes a clear rule of adjudication, by which the rights of parties are ascertained; and it is impossible that an executive officer should regard that as an objection to the grant of a patent which the courts of law are bound to overrule as unavailable. The objection, therefore, which is now presented—that an original bona fide inventor in this country, who verily believed himself the original and first inventor or discoverer at the time of his application, and did not know or believe that his invention or discovery was ever before known or used; and when, in fact, it had not been before invented or discovered by any other person in this country, and had not itself, or any substantial part of it, been before patented or described in any printed publication in any country; that the American inventor, in such a case, is not entitled to a patent for his discovery, because it had been before known or used in a foreign country,—is directly opposed to the intent, the policy, and express words of the act of congress, and is without any legal foundation.

In such a case the American inventor is, in contemplation of law under the provisions of the act of congress, the original and first inventor. The fact that an invention not patented, and not described in any printed publication, has been before known or used in any foreign country, is rendered immaterial, except so far as it may have come to the knowledge of the applicant, and may thus conflict with the oath or affirmation which he is required to take, or with his claims as an original inventor. If he is an original inventor, and is in a condition to take the oath or affirmation prescribed, then the act removes the supposed objection out of the way, requires the commissioner to issue the patent, the courts to declare it valid, and establishes the American right, to the exclusion of the foreign discovery, which has not, in either mode indicated by the act of congress, been communicated to the public.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, sir, your obedient servant,

Isaac Toucey.

Hon. James Buchanan, Secretary of State.

CRANCH, Chief Judge. The commissioner, upon hearing, decided that Mr. Bain's claim interfered with Mr: Morse's, and that Mr. Morse was the first inventor, and rejected the claim of Mr. Bain. From this decision Mr. Bain has appealed. It is contended by the counsel of Mr. Morse that the judge, upon appeal, has no jurisdiction of the question of interference; that an appeal is

404given solely upon the question of priority of invention; that upon the question of interference the decision of the commissioner is conclusive. Whether it be thus conclusive, then, is the first question to be decided. By the act of [July 4,] 1836, [5 Stat 120,] c. 357, § 7, it Is enacted that “if the specification and claim shall not have been so modified as, in the opinion of the commissioner shall entitle the applicant to a patent, he may, on an appeal and upon request in writing, have the decision of a board of examiners, to be composed of three, &;c; and on examination and consideration of the matter by such board, it shall be in their power, or of a majority of them, to revise the decision of the commissioner, either in whole or in part; and their opinion being certified to the commissioner, he shall be governed thereby in the further proceedings to be had on such application.” This section is applicable to cases where there is no conflicting applicant, and shows that the legislature, by saying “If in the opinion of the commissioner,” &;c., did not intend to make that opinion conclusive. On the contrary, it provides “that the board shall be furnished with a certificate in writing of the opinion and decision of the commissioner, stating the particular grounds of his objection, and the part or parts of the invention which he considers as not entitled to be patented; and that the said board shall give reasonable notice to the applicant, as well as to the counsel, of the time and place of their meeting,” &;c. All these provisions were evidently intended to enable the board of examiners to revise the opinion and decision of the commissioner, and show that his opinion was not to be conclusive. By the eighth section of the same act (1836) it is enacted “That whenever an application shall be made for a patent which, in the opinion of the commissioner, might interfere with any other patent for which an application may be pending, or with any unexpired patent which shall have been granted, it shall be the duty of the commissioner to give notice thereof to such applicants or patentees, as the case may be; and if either shall be dissatisfied with the decision of the commissioner on the question of priority of right or invention on a hearing thereof, he may appeal from such decision on the like terms and conditions as are provided in the preceding section of this act; and the like proceedings shall be had to determine which, or whether either, of the applicants is entitled to receive a patent as prayed for.” The question of priority of right or invention necessarily implies interference. The commissioner, before he could decide the question of priority, must have decided that of interference, for without interference there can be no question of priority. Before I can have jurisdiction of the question of priority, I must be satisfied that there is an Interference; and I must decide the question of jurisdiction, as well as any other question which arises in the cause. The opinion of the commissioner (mentioned in the eighth section, that interference exists) only justifies him in giving notice thereof to the other applicant and appointing a day to hear the parties upon that question. He decides it only pro hac vice, and for that purpose only. Upon the hearing, he is to decide; and from that decision, if either shall be dissatisfied with it on the question of priority, including that of interference, he may appeal; and upon such appeal, as I understand the law, the judge, in case of real interference, may “determine which, or whether either, of the applicants is entitled to receive a patent as prayed for.” The scope thus given to the judge is broad enough to include the question of interference, as well as that of priority, if it should arise. By the act of [March 3,] 1839, [5 Stat. 354,] c. 88, § 11, it is enacted “That in all cases where an appeal is now allowed by law from the decision of the commissioner of patents to a board of examiners, provided for in the seventh section of the act to which this is additional, the party, instead thereof, shall have a right to appeal to the chief justice of the district court of the United States for the District of Columbia by giving notice thereof to the commissioner and filing in the patent office, within such time as the commissioner shall appoint, his reasons of appeal specifically set forth in writing, and also paying into the patent office, to the credit of the patent funds, the sum of twenty-five dollars. And it shall be the duty of the said chief justice, on petition, to hear and determine all such appeals, and to revise such decisions, in a summary way, upon the evidence adduced before the commissioner, at such early and convenient time as he may appoint, first notifying the commissioner of the time and place of hearing, whose duty it shall be to give notice thereof to all parties who appear to be interested therein in such manner as the said judge shall prescribe. The commissioner shall also lay before the said judge all the original papers and evidence in the case, together with the grounds of his decision, fully set forth in writing, touching all the points involved By the reasons of appeal; to which the decision shall be confined.”

One of the reasons of appeal in this case is that there is no real and substantial interference between the two applications. The question of interference, therefore, is involved by the reasons of appeal, and must be decided by the judge. By limiting the jurisdiction of the judge to the points involved by the reasons of appeals, the legislature has affirmed it to that extent. The interference mentioned in the eighth section of the act of 1836 must be an interference in respect to patentable matters; and the claims of the applicants must be limited to the matters specifically set forth as their respective inventions; and what is not thus claimed may, for the purpose of this preliminary

405inquiry, be considered as disclaimed. The question, then, is, Does Mr. Bain claim a patent for any matter now patentable for which Mr. Morse claims a patent? To answer this question it is necessary to ascertain for what patentable matter Mr. Morse now claims a patent. In his specification filed January 20th, 1848, he says: “What I claim as my own invention and improvement is the use of a single circuit of conductors for the marking of my telegraphic signs, already patented, for numerals, letters, words, and sentences, by means of the decomposing, coloring, or bleaching effects of electricity acting upon any known salts that leave a mark, as the result of the said decomposition, upon paper, cloth, metal, or other convenient and known markable material. I also claim the invention of the machinery, as herein described, for the purpose of applying the decomposing, coloring, or bleaching effects of electricity acting upon known salts, as hereinbefore described.” The commissioner in his written decision in this case says: “Such use of a single circuit” (i. e., to produce marks upon chemically-prepared paper) “is not the point at issue; nor is this claimed by either party. Said Morse claims using a single circuit of conductors for a certain purpose or in a certain way, viz., to mark his telegraphic signs, and also claims the machinery by which he accomplishes this purpose. Said Bain does not specifically mention in his claim using a single circuit, though this must be considered as an essential part of his invention and claim, and is necessarily involved in the final clause of his claim, to wit: ‘So that in either case these form the received communication, substantially in the manner and with the effects described and shown.’ “The commissioner proceeds: “The third clause of the claim of said Bain, with which the two claims of said Morse interfere, is as follows, to wit: ‘Third. The application of any suitable chemically-prepared paper, without regard to the chemical ingredients used for such a purpose, to receive and record signs forming such communications, such signs being made by the pulsations of an electric current or currents transmitted from a distant station, said current operating directly and without the intervention of any secondary current or mechanical contrivance, through a suitable metalmarking style that is in continuous contact with the receiving paper, thereby making marks thereon, which marks correspond with groups of perforations in the paper composing the transmitted communication, or may be given by the pulsations from the spring 45 and the block 40; so that in either case these form the received communication, substantially in the manner and with the effects described and shown, including any merely practical variations, analogies, and equivalents in the means employed and the effects produced thereby.’” The commissioner in his written decision says: “The invention, it will be seen by the reference to the specifications of the parties respectively, does not consist in the use of the electric current to make marks upon chemically-prepared paper, nor making marks through a single line of conductors; nor could a claim to either of these devices have been entertained as patentable, as they have been long known.” Again, it is said by the counsel of Mr. Morse: “It is admitted that neither could patent the battery, the circuit, “the prepared paper, or the marking by the electro-chemical process. It was only a new combination of the several parts, so as to produce a new result, or an old result in a better manner, that either could patent Again, the commissioner in his “reasons of decision” says: “It is true, as Mr. Bain asserts, that no one can monopolize the use of air, fire, or water, but it is equally true that any one can monopolize the use of air, fire, or water upon certain principles of operation which he may have invented or discovered; and this is precisely what the respective claimants in this case demanded as their right, and which gave rise to the interference, viz., each claimed the right to use, and exclude others from using, galvanic power to mark certain signs (which signs have already been patented by said Morse) upon chemically-prepared paper through a single circuit of conductors. A single circuit of conductors consisting either wholly of wire, or in part of wire and part of earth, for telegraphic purposes was not new. The signs or signals to be marked were not new, the same having been before patented by said Morse; and chemically-prepared paper for receiving telegraphic signs by galvanism was not new, the same having been patented in England in 1836 by Mr. E. Davy (7719 of 1836). Moreover, the use of a single telegraphic circuit for making the aforesaid signs upon paper was not new, the same having been before patented by said Morse. Neither party claimed any one or any two of the above elemental features. The invention of each was made up of the three combined, and the advantages claimed to have been discovered by each in these combined operations were identical.”

There is nothing, then, now patentable in the Morse claim, left to be interfered with, except his claim of a patent for his invention of the machinery described in his specification or for his combination of machinery and materials as described therein. The claim of each applicant, therefore, is reduced to the claim for the combination of machinery and materials which he has invented, and does not include any of the matters claimed in his specification which are not now patentable. These combinations seem to me to be far from identical. Mr. Bain includes in his combination the use of the perforated paper for composing the communication and of the style which passes the electric current through the perforator and the machinery for transmitting the same communication to

406several different places at the same time. It is said that the style is not new; but he makes it an ingredient in his combination—and in that respect his combination differs from that of Mr. Morse, and it is a very important item—in connection with the perforated paper. He includes in his combination new patentable matter with old matter not patentable, and thereby makes a new patentable combination. This new matter thus introduced into the combination is admitted to be patentable in itself without combination with the old unpatentable matter, and, indeed, it seems to be a great improvement in the transmission of telegraphic information. But it is said that Mr. Bain is only authorized to obtain a separate patent for these inventions, and cannot claim a patent for his new combination of the old and new together. If, however, his new combination of old materials be patentable, which must be admitted, or it would not interfere with Mr. Morse's claim, it seems to be not the less patentable because it includes the new matter in connection with the old. The old matter may not in itself be patentable, but joined to the new matter a combination may be formed which may be patented. He is not obliged to take separate patents for each new patentable matter. He does not now ask for them. He may be willing to ask only for a limited use of those new matters, to wit, in combination, and not for an exclusive use of them for every purpose to which they may be applicable. Mr. Godson (Gods. Pat. p. 63) says: “A combination of old materials, when in consequence thereof a new effect is produced, may be the subject of a patent. This effect may consist either in the production of a new article, or in making an old one in a better manner or at a cheaper rate. This manufacture may be made of different substances mingled together, or of different machines formed into one, or of the arrangement of many old combinations. Each distinct part of the manufacture may have been in common use, and every principle upon which it is founded may have been long known, and yet the manufacture may be the proper subject for a patent. It is not for those parts and principles, but for the new and useful compound or thing thus produced by combination, that the grant is made. It is for combining and using things before known with something then invented, so as to produce an effect which was never before attained.”

The counsel for Mr. Morse in argument said: “It is obvious, and is admitted by our adversaries, that Morse's instrument is a very different thing in form and structure from Bain's.” But form and structure are very important matters in machinery; and if they enable the operator to do the work in a better manner, or with more ease, or less expense, or in less time, it is no interference, but it is an improvement for which the inventor may have a patent. “When the application is for a patent for a combination of machinery and materials, form and structure become substance. They are the essence of the invention; and an admission that Morse's instrument is a very different thing in its form and structure from Bain's, is an admission of a fact which is primafacie evidence, at least, that there is no interference between the two, and throws the burden of proof upon the other side. There was no evidence laid before the commissioner of patents upon the question of interference; so that he must have adjudged the interference upon a comparison of the two specifications, possibly without considering that the only patent either could obtain would be a patent for his own combination—all the materials of which Mr. Morse's combination consists being old and not now patentable. The question is not now whether the claims of Mr. Bain and Mr. Morse interfere as to matter not now patentable, but whether they interfere as to matter now patentable; and the only matter now patentable in Mr. Morse's specification is his own combination of machinery and materials. That combination constitutes his machine, and his machine is admitted to be a very different thing in its form and structure from Mr. Bain's. Form and structure constitute the identity of machinery. The combination consists in form and structure, and the patent, if issued, will, I presume, be issued for the form and structure of the instrument. It being admitted that the form and structure of Mr. Bain's instrument is very different from Morse's, there can be no interference in that respect. And if form and structure constitute the identity of machinery, there is no interference in the two instruments; and if the instruments are the combinations, or the result of the combinations, for which patents are now claimed, there is no interference in the two instruments in regard to any matter now patentable. But it is not necessary to rely alone upon the admission of Mr. Morse's counsel to show that there is a great difference between the machines used by the contending applicants to effect the objects, i. e., the rapid transmission of intelligence by the power of the electric current Any one who will compare the two specifications and drawings and models will at once perceive that difference.

A patentable improvement is not an interference. The commissioner in his written decision says: “It appears from the records of the office that the application by said Alexander Bain, subject of Great Britain, was made April 18th, 1848; and upon examination of his claim it was found that the before mentioned claim could be admitted to patent, no invention of a like character appearing in the public records of the office nor in any printed publication. Prior, however, to the final issue of the case, the secret archives were consulted, and it was found that an application filed by Samuel F. B. Morse

407January 20th, 1848, had been there deposited, in compliance with provisions of the law, which presented claims conflicting with those before mentioned set up by said Bain.” This shows that but for the supposed interfering claim of Morse Mr. Bain was entitled to his patent; and if there be no interference in respect to patentable matter, he is still entitled to a patent for his own combination. But the counsel for Mr. Morse say: “There is an interference in that Bain's third claim palpably covers the whole of Mr. Morse's first claim, and, if granted, Bain could do all that Morse claims an exclusive right to do. He could write Morse's characters precisely as Morse does; and that therein consists the interference.” But the only matter now patentable and claimed in Mr. Morse's specification is his peculiar combination of materials and machinery as therein described. All the materials used in the combination are old, and he will not under his patent be entitled to the exclusive use of any of them separately, or in any other combination than that which he has described in his specification. There cannot be a patent for a principle, nor for the application of a principle, nor for an effect. Two persons may use the same principle, and produce the same effect by different means, without interference or infringement, and each would be entitled to a patent for his own invention. Gods. Pat pp. 63, 68, 74. So in the present case, although the power used by both applicants is the same, and the subject the same, yet, as the effect is produced by means which appear to me so different as to prevent an interference, the question of priority of invention does not arise. It is not, therefore, a case under the eighth section of the act of [July 4,] 1836, but under the seventh section of the same act, [5 Stat. 120;] so that each of the applicants may have a patent for the combination which he has invented and claimed and described in his specification, provided he shall have complied with all the requisites of the law to entitle him to a patent. If this were a doubtful question I should think it my duty to render the same judgment, so as to give Mr. Bain the same right to have the validity of his patent tested by the ordinary tribunals of the country which Mr. Morse would enjoy as to his patent, and finally, to obtain the judgment of the supreme court of the United States upon it. For if the commissioner and the judges should reject Mr. Bain's application for a patent, the decision would be final and conclusive against him unless he could obtain relief by a bill in equity under the tenth section of the act of 1836, [5 Stat. 121,] and the tenth section of the act of 1839, [Id. 354,] which it is said is doubtful.

I am therefore of opinion, and so decide, that there is no interference in relation to any matter (contained in their respective specifications) now patentable, and therefore that Samuel F. B. Morse is entitled to a patent for the combination which he has invented, claimed, and described in his specification, drawings, and model, and that Alexander Bain is entitled to a patent for the combination which he has invented, claimed, and described in his specification, drawing, and model, provided they shall respectively have complied with all the requisites of the law to entitle them to their respective patents. I deem it unnecessary, therefore, to decide upon any other points involved by the reasons of appeal.

[NOTE. Patent No. 6,420 was granted to S. F. B. Morse, May 1, 1849. For other eases involving this patent, see Morse v. O'Reilly, Case No. 9,858, Id. 9,859; O'Reilly v. Morse, 15 How. [56 U. S.] 62; Morse and Bain, Telegraph Case, Case No. 9,861.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.